A Surgical Theater of Firsts

One day in 1960, during a trip to Dallas for the dedication of the Fondren Health Center at Southern Methodist University, prominent Houston philanthropist Ella Fondren fell and fractured her hip. She was flown to Houston Methodist for surgery and spent the next six months in the hospital recovering.

Perched in Room 807, which she later proclaimed her “favorite room,” Fondren often looked out the window, but not to gaze up at the stars or contemplate what lay beyond the horizon.

Instead, she began to study an undeveloped parcel of land north of the hospital that she could see from her bed. Soon, she became consumed by an idea.

“We’ve got to build smething on that property over there, and right away,” she said, repeatedly, to Ted Bowen, the hospital’s president.

Chief of orthopedic service, Joe King, M.D., and world-renowned cardiac surgeon Michael E. DeBakey, M.D., proposed an expansion to house orthopedic and cardiovascular research.

Fondren and partnering foundations agreed and launched a $9 million campaign to develop the Fondren-Brown Cardiovascular and Orthopedic Research Center. On Oct. 27, 1964, Ella Fondren and George R. Brown plunged their ceremonial silver-polished shovels into the parcel of land Fondren had admired from her hospital room.

This was the beginning of a new era in Houston Methodist’s history.

George R. Brown, far left, and Ella Fondren, right, at the groundbreaking ceremony for the Fondren-Brown Cardiovascular and Orthopedic Research Center in 1964.

The red line

In April 1968, the Fondren-Brown Cardiovascular and Orthopedic Research Center began opening in stages.

The center consisted of two adjoining structures: The Ella F. Fondren Building and the Herman Brown Building. The six-story Fondren Building occupied 165,000 square feet devoted to orthopedic and cardiovascular research, including 50 beds for teaching and research. The neighboring five-story Brown Building consisted of 108,000 square feet and housed clinical and laboratory areas for cardiovascular conditions. Over the next decade, additional floors were added to the buildings to accommodate more research facilities, cardiovascular inpatient care and medical services.

But the center’s pièce de résistance? Eight specialty operating rooms and a cardiac intensive care unit.

“To be able to do the surgeries that we were doing at that time was a real thrill. We were right on the cutting edge of the whole development of cardiovascular surgery,” said George Noon, M.D., DeBakey’s surgical partner of more than 40 years.

“When I finished my residency and joined the faculty, we were doing more procedures than anyone else in the world.”

The cardiac ICU was staffed with nurses specially trained by the surgeons. It was a relatively novel concept at that time, but DeBakey appreciated the importance of post-operative care.

DeBakey served in the U.S. Army’s Office of the Surgeon General during World War II and had the vision to create a ward where surgical residents would train with the same exacting, militaristic approach under his civilian command.

He suffered no fools and demanded unyielding excellence from his staff. His training program became a rite of passage.

“Long before I knew that I was coming down to Houston, we all knew about the Fondren-Brown OR with a combination of terror and awe because it had a reputation as being a fearsome environment for surgeons to work in,” said Alan Lumsden, M.D., who became chief of cardiovascular surgery at Houston Methodist DeBakey Heart & Vascular Center in 2008.

Alan Lumsden, M.D.

“Most of the trainees were scared of Dr. DeBakey when they came through the program,” Noon said. “That’s because, if you didn’t get things done the way they were supposed to get done, he would strongly criticize you. But he was able to get the most out of everybody who worked for him.”

DeBakey’s residents were required to undergo a rigorous two-month stint in the cardiac OR and ICU, where they remained on call 24/7 without leaving. Their confinement was demarcated by a physical red line that was taped around the unit.

“The red lines are famous in the [cardiovascular] world because the fellows who were going in the ICU rotation were shown the red lines and told that if they stepped across that red line in the next two months, they’d be fired,” Lumsden said. “I assumed it was part of the urban legend about the place.”

Accounts of DeBakey’s ICU were passed down and shared cohort after cohort, generation after generation. To those who never endured his training, it was hard to tell fact from fiction. But it wasn’t an urban legend at all.

Michael Reardon, M.D., a cardiac surgeon at Houston Methodist who trained under DeBakey from 1978 to 1983, recalled only getting to see his pregnant wife and baby girl on Saturdays when they visited him at the hospital to deliver clean socks and underwear. He would see them for half an hour at a time and then go back to being sequestered in the ICU.

“There was a window at the back, or the front, of the ICU that would open about [an inch]. At about two in the morning, I’d go open the window and stick my nose out just to smell the air,” Reardon said.

Michael Reardon, M.D.

The training wasn’t meant to be cruel. The purpose was plain and simple: To ingrain responsibility and accountability in surgeons.

“[Patients] can die at our hands, or they can get much better in our hands. If they die after you’ve operated, it is on you. You made a contract with that patient,” Reardon said. “That’s one thing that Dr. DeBakey taught us: It’s attention to every detail because, if you don’t and if they die, it’s your

fault.”

A great leader

Because of DeBakey’s intense approach, many who trained with him—including Noon and Reardon—became part of an elite league of surgeons who ascended to the highest rungs of their profession, pioneering new surgical interventions and making their own marks on medical history. But the price of admission was trial by fire in the Fondren-Brown OR.

“The great leaders in surgery aren’t the individual surgeons,” Reardon said. “The great leaders know how to spot talent and develop talent. Dr. DeBakey was a great organizer: He organized one of the greatest operating rooms and ICUs that allowed them to do these things. Then he spotted talent, organized that talent, and gave that talent not just permission, but incentive to achieve.”

The OR was ground zero to many firsts, starting in its inaugural year. DeBakey and Noon performed the world’s first simultaneous multi-organ transplant in August 1968. In 1980, Noon led a surgical team that performed the first angioplasty and the first rotational atherectomy that same year.

But national momentum in cardiac surgery was plateauing around the time the center began construction. Interest in heart transplants waned due to poor survival rates from organ rejection.

Between 1964 and 1980, no new major landmarks in transplantation were made in the country, but important progress in immunology research helped lay the groundwork for future innovation. In particular, the development of cyclosporine—an immunosuppressive drug that prevents the body from rejecting kidney, heart and liver transplants—significantly improved transplant success rates and renewed hope in the field.

In 1985, surgeons performed the first heart-lung transplant in Texas. In 1998, Reardon performed the first successful autotransplant for cardiac malignancy. In 2005, Lumsden and Reardon pioneered the first hybrid procedure in the country to repair a large aneurysm of the aortic arch, during which they lowered the patient’s body temperature until it reached a deep hypothermic state to effectively stop the heart.

“If I see further, it’s because I stand on the shoulders of giants. We didn’t get here all on our own,” Reardon said. “We got here because people worked really hard and went through a time when mortality in heart surgery was common. They would fight through these tough cases, people would die, and they would pick themselves up and go back to work the next day. If they hadn’t had that type of self-discipline and courage, we wouldn’t be where we are today.”

‘The next great thing’

This summer, more than 50 years after Ella Fondren envisioned Houston Methodist’s burgeoning future from her bed in Room 807, the hospital will open a gleaming new facility. Walter Tower features state-of-the art operating rooms that will replace the Fondren-Brown OR. After running 24/7 for half a century, the Fondren-Brown OR will be demolished and turned into preoperative rooms.

It’s a bittersweet finale, considering the groundbreaking innovation and history-making surgical procedures that took place within those walls. But even DeBakey wouldn’t let nostalgia impede progress.

“It’s a little sad, but you know what? If you asked Dr. DeBakey, he’d be the first to move on to something better. He would move on in a heartbeat,” Reardon said. “He was always looking for the next great thing. If the next great thing required him to get rid of the Fondren OR, he would have done it in a nanosecond.”

DeBakey died in 2008 at age 99. Reardon recalled a conversation they had a month before DeBakey’s death.

“The guy was still talking about trials he wanted to do and things he wanted to achieve at 99. He was always moving forward,” Reardon said. “He would not mourn the Fondren OR. He would be appreciative of what it has given everyone, but he would look forward to the future.”

For Noon, who shares DeBakey’s progressive outlook, the Fondren-Brown OR’s legacy will live on as new innovations are made.

“Of course, I’m going to miss it,” Noon said. “But then you have to realize you have to miss it … to come up with other things.”

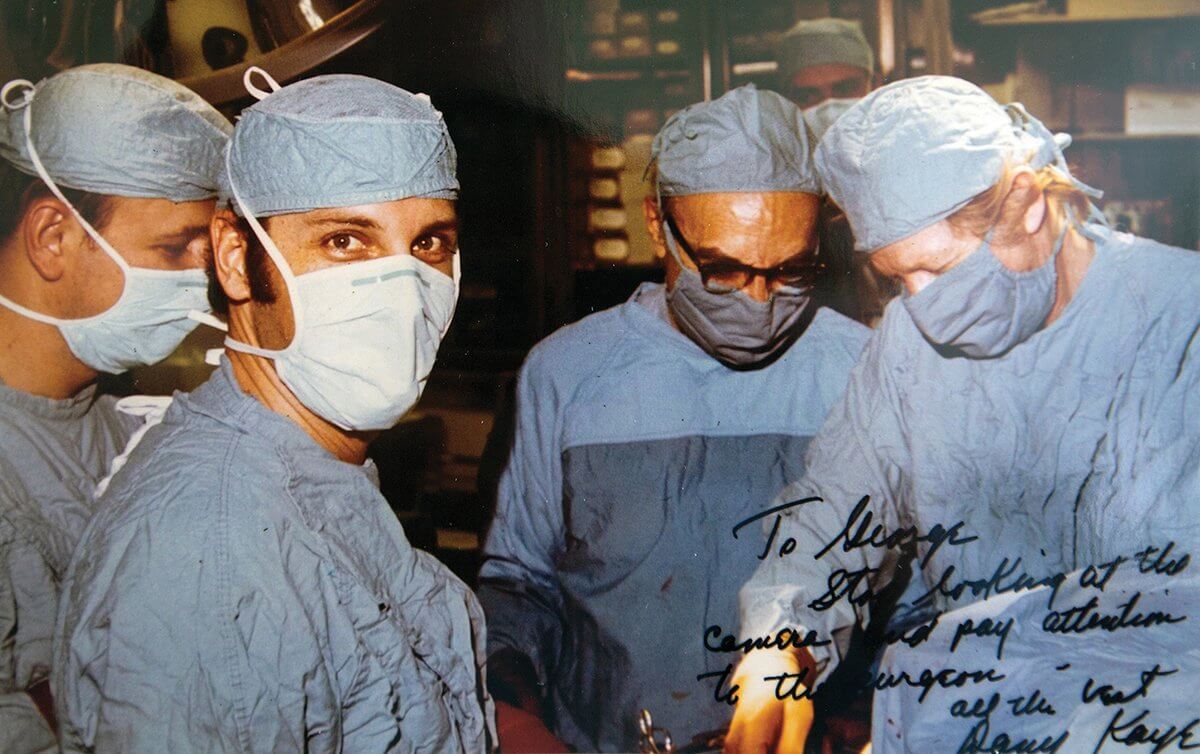

George Noon, M.D., in the operating room decades ago, with Dr. Michael DeBakey (second from right) and entertainer Danny Kaye (far right).

*****

Walter Tower

Clouds are reflected in Houston Methodist’s new Walter Tower, 6551 Bertner Ave., just after sunrise.

In August 2018, more than 50 years after the Fondren-Brown center opened, Houston Methodist Hospital is expected to premiere the Paula and Joseph C. “Rusty” Walter III Tower. The 22-story building will include 366 patient beds, 18 high-tech operating suites for neurosurgery and cardiovascular surgery, six acute care floors, two intensive care floors, and a helipad.

“The OR is as modern as modern can be,” said Alan Lumsden, M.D., chief of cardiovascular surgery at Houston Methodist DeBakey Heart & Vascular Center. “I’ve described what is going to open as the most technologically advanced operating rooms in the world.”

Thanks to a new joint venture between Houston Methodist and Siemens Healthineers, five of the operating rooms will be “hybrid” operating rooms equipped with the latest in medical imaging. By incorporating medical imaging and diagnostic tools—such as angiograms, magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography— with 3-D and augmented reality technology in the operating room, surgeons will be able to perform safer, more effective procedures.

As Houston Methodist continues to compete with major hospitals around the country, the move into the modern age of digital technology is an important step in the hospital’s evolution.