A Solid Foundation for Biomedical Research

Entering the Biosafety Level 4 (BSL4) facility at The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston (UTMB), often described as “a submarine inside of a bank vault,” is an intricate process. Even before stepping inside the building, researchers must pass through a security checkpoint, manned 24 hours a day, before navigating a series of locked doors, elevators and stairwells, all of which require electronic or other forms of security clearance. Closed circuit cameras dutifully monitor the entire journey between the building entrance and laboratory entrance.

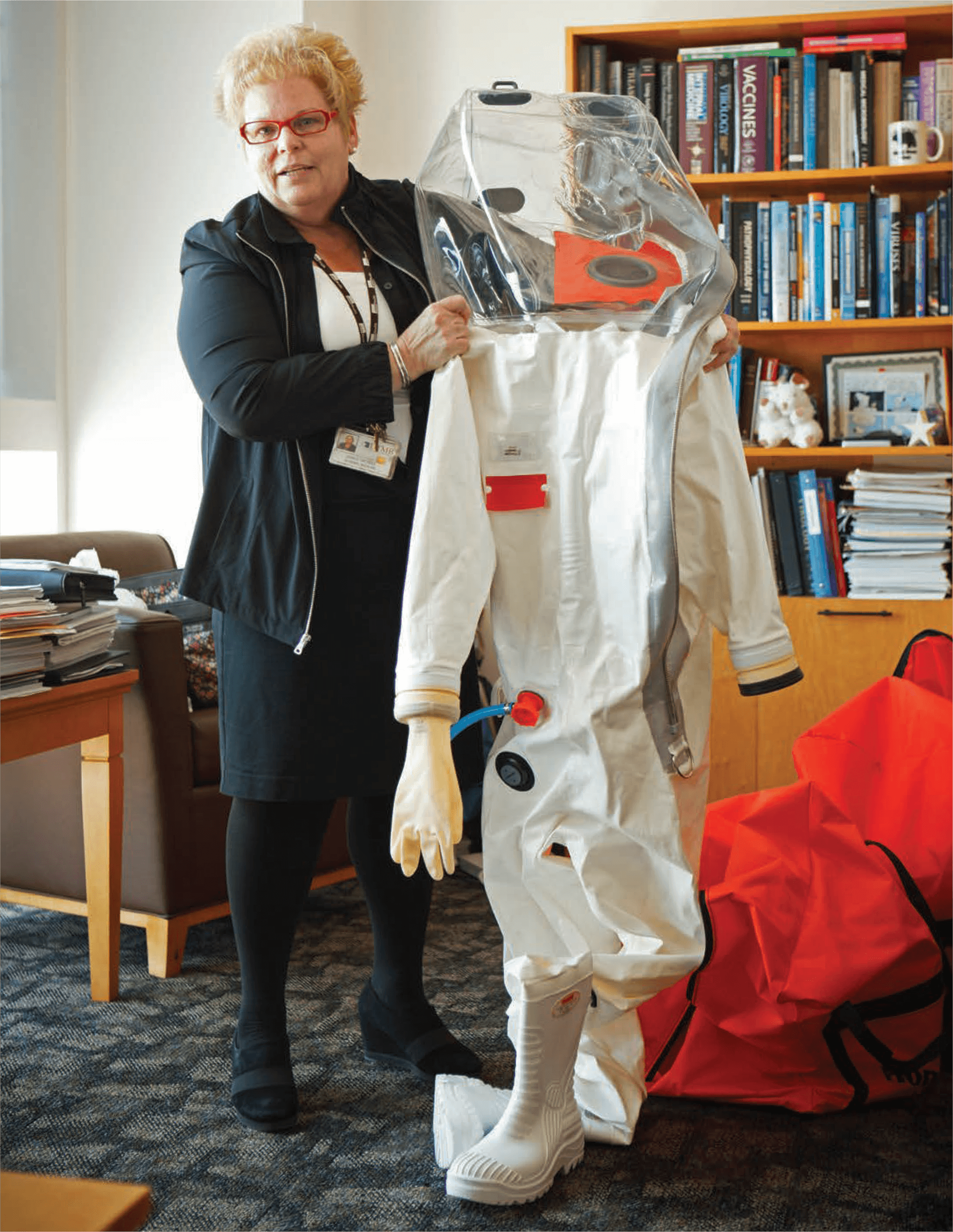

As researchers prepare to cross the threshold into the sealed capsule of the laboratory itself, they must pass the final locked door to enter a buffer corridor around the lab. Ensuring that security is air-tight, negative air pressure throughout the buffer corridor and the lab itself maintains air flow from “safer” areas into the BSL4 area— another redundancy built into the system to counteract the remote potential for infectious particles to escape into the air. Once they’ve donned positive-pressure suits to protect against any infectious material that might become airborne within the containment lab, scientists pass through an airtight door into the laboratory area. After all that, holding your breath hardly seems necessary.

“The complexity and redundancy in our systems ensures that we’re secure because we take great care in making sure that everything that leaves the laboratory is completely inactive, whether it’s in the wastewater or the air that you breathe,” said James LeDuc, Ph.D., director of the Galveston National Laboratory (GNL) at UTMB. “About half of the building is dedicated to mechanical space just to ensure environmental safety. We have a staff of highly trained professionals working on those systems.”

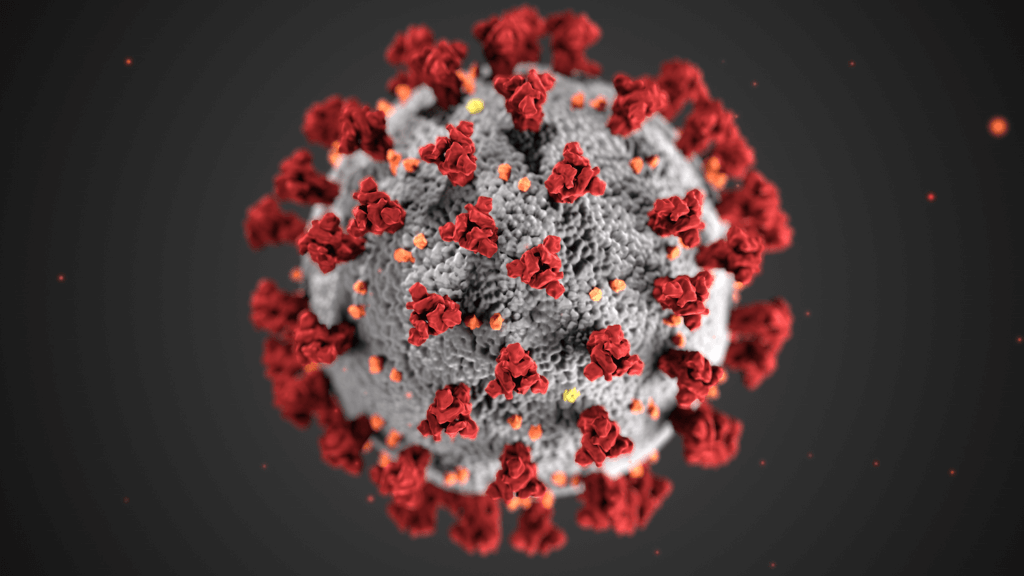

Consisting of 96,000 square feet of total laboratory space and a projected economic impact of $1.4 billion stateside over the course of 20 years, work within the Galveston National Laboratory complements and enhances UTMB’s decades of prominence in biomedical research. The facility serves as a crowning achievement upon a series of advances that have taken UTMB’s infectious disease program from a local point of pride to an internationally renowned resource. “We have several main thrusts—it’s all about bringing the academic community into the response for both national security, in terms of biodefense, as well as emerging infectious diseases,” explained LeDuc. “Through that, we strive to really harness the research capabilities of the academic community to really understand how these unique diseases cause illness in humans.”

Formally dedicated on November 11, 2008, the Galveston National Laboratory provides much needed research space and instrumentation to safely develop therapies, vaccines and diagnostic tests for naturally occurring emerging diseases such as SARS, West Nile encephalitis and avian influenza—and for microbes that might be employed by terrorists. Investigations within the GNL have the potential to spur the emergence of products such as novel diagnostic assays, improved therapeutics and treatment models, and preventive measures such as vaccines.

Since the early days of the 20th century, when UTMB physicians provided care for victims of the 1918 influenza pandemic and outbreaks of the bubonic plague and yellow fever, UTMB has been actively engaged in influencing infectious disease research. In the past few decades, emerging and reemerging infectious diseases have posed a steadily growing threat, thanks to rises in human population size and density, rapid environmental change, and increases in the speed and volume of transportation.

Microbes once limited to remote regions of the globe have shown the potential to penetrate the developed world—viruses like SARS and West Nile. For germs in a world where transportation barriers are eroding, international boundaries mean little.

This escalation prompted David Walker, M.D., director of UTMB’s Center for Biodefense and Emerging Infectious Diseases, to propose the creation of the United States’ first full-scale Biosafety Level 4 laboratory on a university campus. In the mid 1990s, Walker’s recruitment of eminent virologists Robert Shope and Robert Tesh, who left Yale for Galveston in 1995, commanded global attention while simultaneously stimulating the expansion of UTMB’s infectious disease program. They brought with them the World Reference Center for Arboviruses, a priceless collection of thousands of different virus strains collected from all over the globe and freeze-dried for storage. As Walker enlisted a talented troupe of scientists to join his expanding team in Galveston—including Alan Barrett, Ph.D., an eminent pathologist and current director of UTMB’s Sealy Center for Vaccine Development, and Scott Weaver, Ph.D., a pathology professor who would become scientific director of the Galveston National Laboratory— he realized the necessity of a maxi- mum containment lab to work on the diseases that interested them, from tick- borne encephalitis to chikungunya.

After an extended approval process while community support was garnered and fears were assuaged, the Robert E. Shope M.D. BSL4 Laboratory broke ground in 2002 and was officially dedicated in 2004. “The Shope Laboratory turned out to be incredibly visionary,” recalled Weaver. “It opened up new opportunities for our research programs and gave us experience not only in running this facility but interacting with the community here to develop the kind of relationship that you need to secure that level of trust.” UTMB faculty meet regularly with their Community Advisory Board, a group of approximately 60 members of professional and civic organizations, to keep them informed on the important work being done at UTMB and to get their help in sharing the information with the community at large. A seven-member GNL Community Liaison Committee also meets regularly, acting as UTMB’s eyes and ears in the community as well as a sounding board.

“The Shope Laboratory was a revolutionary thing—it proved that we could run a BSL4 laboratory safely and securely,” said Walker. “After the community had accepted us, I hired consultants and brought groups of people here on a regular basis, people who ran labs like this at other places like the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and they helped us figure out how to proceed.”

In spite of the tremendous success of the Shope Lab, it wasn’t large enough to conduct certain types of experiments, especially those that involved work with animals larger than rodents. In the wake of September 11th and the subsequent anthrax attacks, the United States government vied for the creation of more facilities to provide research to help defend against bioterrorism attacks. Under the direction of the U.S. Congress, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases/National Institutes of Health (NIAID/NIH) began a nationwide search for a location to build a National Biocontainment Laboratory.

“The Shope Lab was running around the same time that we drafted our application, and the committee that determines the funding for these types of programs came to visit for a site inspection,” said Weaver. “They came down, and, lo and behold, a tropical storm was coming through. Some people thought that this was the worst possible luck, but the university was still open for business and the lab was running smoothly. I think that helped us convince them that we can build these facilities safe enough to withstand any storm.”

One of two National Biocontainment Laboratories constructed with funding awarded in October 2003 by the NIAID/NIH, the Galveston National Laboratory broke ground in 2005. The sturdy foundations of UTMB’s new facility would be unexpectedly put to the test several years later, when Hurricane Ike struck the Gulf Coast in 2008. “Hurricane Ike was devastating,” said Walker. “But there was one really good outcome, an unmitigated, beneficial effect: it proved that the GNL had been designed appropriately. It was the only building that was completely undamaged. Everyone was criticizing us for building a BSL4 lab on a barrier island that’s constantly hit by hurricanes, but this proved that we had designed our facility soundly and it could function safely.” The GNL was formally dedicated just a few short months after the hurricane, and has been running ever since.

Propelled forward by a critical mass of expertise, and drawing from the richness of the academic community, infectious disease research at UTMB has consistently tread new territory. Earlier this year, Thomas Geisbert, Ph.D., a UTMB professor of microbiology and immunology, received a $26 million grant for Ebola research, work of critical importance as nations struggle to deal with the current outbreak in Africa. Courtesy of a $4.4 million grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and led by co-principal investigator Slobodan Paessler, DMV, Ph.D., a professor in the UTMB department of pathology, researchers are working to create a universal flu vaccine—one that could eliminate the need for an annual flu shot. At a time when research budgets are under stress, UTMB received more than $76 million in NIH funding for federal fiscal year 2013.

“It’s all about the people here,” said Joan Nichols, Ph.D., associate director of research and operations for the GNL and an expert on influenza. “It’s great that we built this incredible building, but it wasn’t until we commissioned it and brought the people in that we started to see the magic happen, which is what drives scientific discoveries.”

“What’s unique about the Galveston National Laboratory, as well as all of our other research facilities, is that they’re such high functioning entities on a university campus,” added Walker. “It’s mutually beneficial, but I think that the GNL benefits even more from being at a university than the other way around. Adding up those benefits, it’s amazing to have all of these colleagues right next door with the ability to interact with one another. The collegial spirit that we’ve cultivated is less common than you might initially imagine. I’ve seen it grow a lot in my time here.” Imparting that collegial mindset upon future generations, the National Biodefense Training Center at UTMB is poised to become a prime site for training aspiring researchers to work in BSL3 and BSL4 facilities across the country.

At the juncture between the private and the federal world and embedded in a textured academic community, UTMB’s research facilities provide incredible value, from the microcosm of the local Galveston community to the macrocosm of global infectious disease research. “We really are a national resource,” said LeDuc. “We have a lot of bright folks here that are doing remarkable work, which could propel us into collaborations with others across the nation and around the world, using these facilities to address larger issues. The idea is for the Galveston National Laboratory to interface with the greater academic community to conduct those experiments that require access to live pathogens. That’s really our sweet spot.”