Inventing a new goo to prevent scarring

In 2016, Tim Keane’s aunt, Jackie, was ready to have more children. She already had one child, but part of her identity was deeply rooted in the idea of raising a big family.

“A big family was important to my sisters and my aunts and my uncles,” Keane said. “I’m one of seven kids. My dad is one of 11. We’re used to having big families. … Being from an Irish Catholic family, that was definitely part of my family’s identity.”

But over the course of three years, each of her pregnancies resulted in miscarriages—leaving her to deal with the guilt and grief of each loss. Her doctors were finally able to solve the mystery of her infertility: Adhesions from a previous cesarean section.

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Looking for the latest on the CORONAVIRUS? Read our daily updates HERE.

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

An adhesion is a band of scar tissue that forms like fibrous webbing between tissues and organs when the body’s repair mechanisms kick in, usually after surgery, infection, trauma or radiation. The body deploys its army of repair cells—including macrophages, fibroblasts and blood vessel cells—to repair the damaged tissue. Because repair cells can’t differentiate between organs, adhesions can form when the surfaces of two organs come in contact with each other, creating a tangled mess of scar tissue that obstructs normal anatomy and organ function.

Scars can form anywhere on the body after an injury, but adhesions are commonly found in the abdomen, pelvis and heart, and oftentimes interfere with the internal anatomy. Abdominal adhesions form in more than 9 out of 10 people who have open-abdomen surgery, according to the National Institutes of Health. Pelvic adhesions occur in 55 to 100 percent of patients who undergo gynecologic surgery, such as a C-section.

“A lot of women, after they have a C-section once, the next time they get pregnant, they’re going to have a C-section again because of adhesions,” Keane explained. “The same adhesions could actually cause miscarriages and cause infertility in those women. That’s what happened with her.”

According to Keane’s studies, more than 500,000 cases of infertility in women and 7 million cases of chronic pelvic pain are associated with pelvic adhesions each year in the United States. A nearly unavoidable certainty, adhesions also can lead to post-surgical morbidity, bowel obstruction and chronic pelvic pain or chronic abdominal pain.

“It’s just, to me, mind-boggling that a surgery that is done to either fix a problem or to do a routine procedure, is something that can cause lifelong complications for a person,” Keane said.

Coming to Houston

When Keane, a bioengineer with a Ph.D. from the University of Pittsburgh, joined the TMC Innovation Institute’s Biodesign program in August 2019, he teamed up with Stephen Ramon, a medical student at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, and Alex Smith, Ph.D., a former research engineer at the Texas Heart Institute, to form TYBR Health.

“We all knew we wanted to build the next something,” said Smith, the company’s vice president of product, “but I don’t think any of us knew what that something would be.”

As they shadowed gynecological, pediatric, orthopedic and trauma surgeons around all the major hospitals in the Texas Medical Center, they realized that adhesions were the biggest problem they observed across all surgical specialties.

The team began developing an idea with Keane’s aunt in mind: “What if we could prevent scars from ever forming?”

“I knew roughly what adhesions were before, but it wasn’t something that I started to think about how I could apply things that I know to this type of problem until it was a personal case,” Keane said. “When you hear about a personal story of the complications and how it can change the course of someone’s life and how they identify themselves, I think that’s when it really hit home for me.”

With Keane’s expertise in extracellular matrices (a 3D structural network of macromolecules that serves as a physical scaffold for surrounding cells), Smith’s background in mechanical engineering and Ramon’s knowledge of medicine and surgery, the trio of scientists developed a pioneering solution for preventing adhesions: the first extracellular matrix hydrogel spray.

How it works

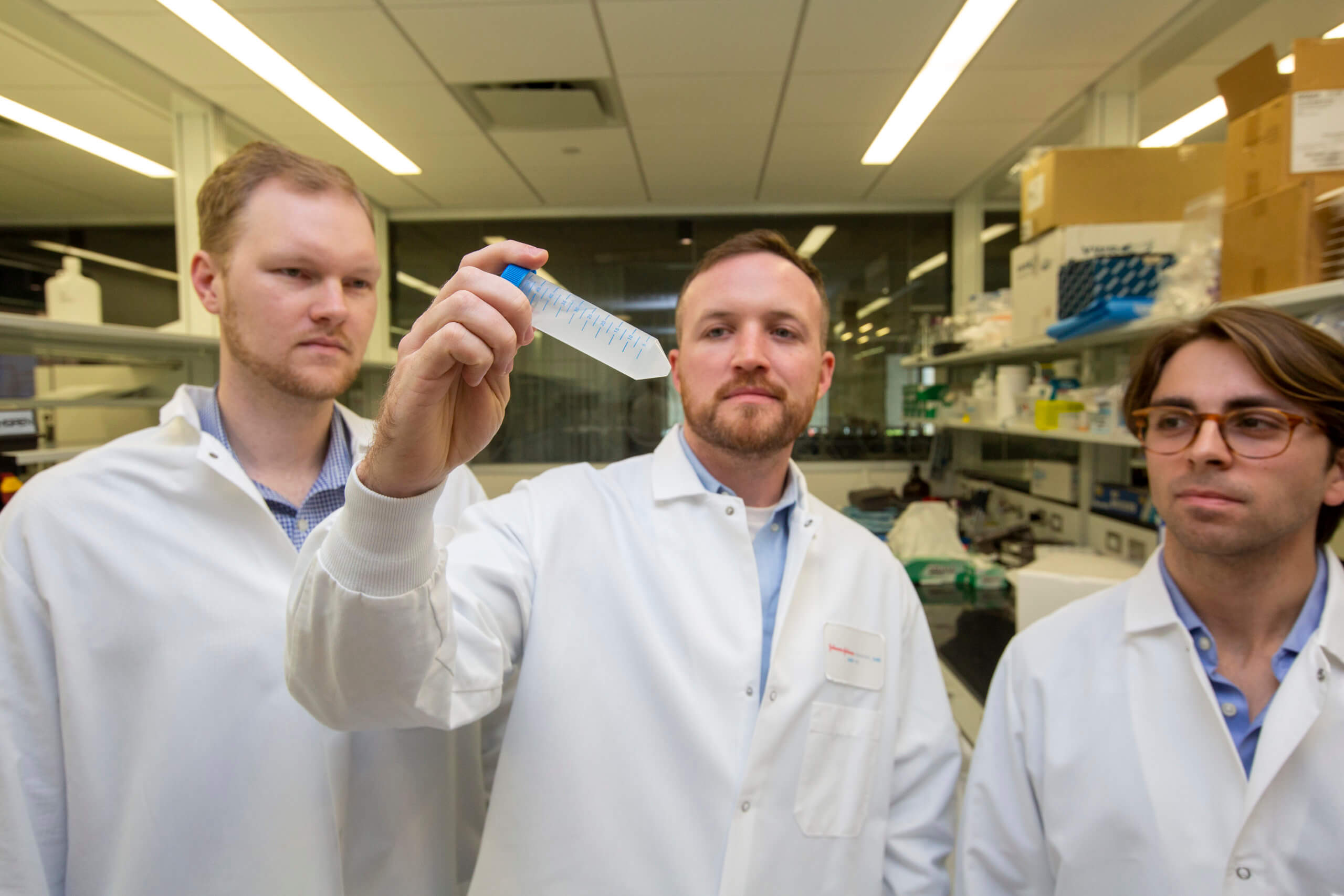

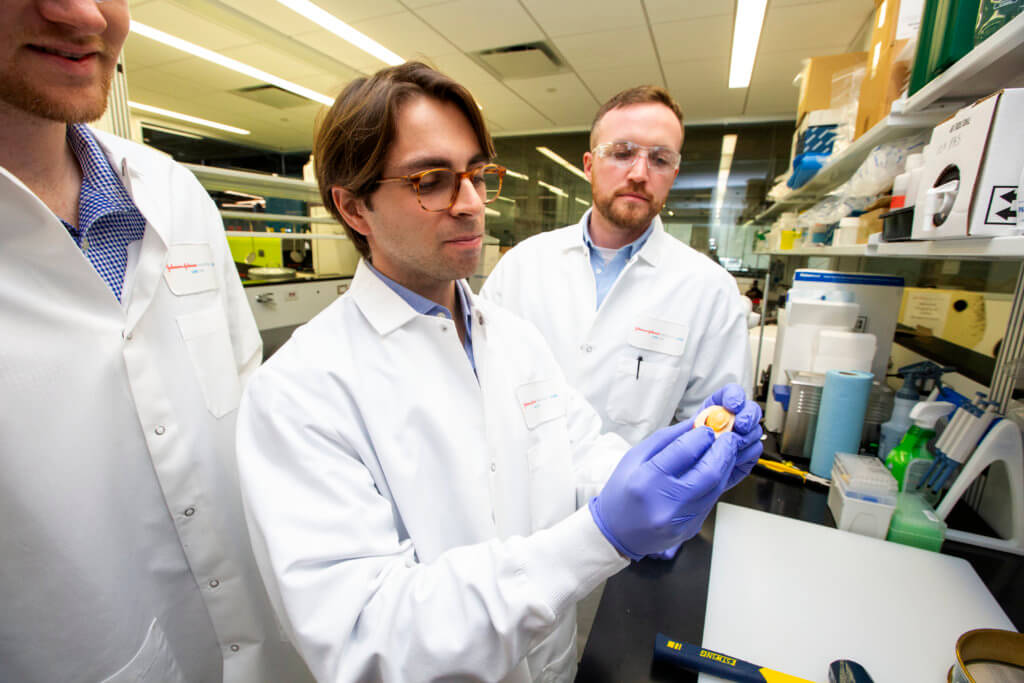

It’s an elegantly simple recipe they cook up in their designated JLABS @ TMC space. First, they chop up bovine tibia into 2-inch chunks and pound out the cancellous bone (the spongy tissue in the center of the bone containing marrow and collagen) using a hammer they purchased at Walmart. Once they decellularize and remove the calcium from the cancellous bone, they pulverize it into a fine powder using a home coffee grinder, which they also purchased at Walmart. They mix the powder into a solution with pepsin enzymes—the same digestive enzyme found in our stomachs that breaks down proteins into smaller amino acids—to create a viscous, gooey concoction that is then sprayed onto the surgical site through a laparoscopic nozzle.

Stephen Ramon, center, demonstrates how they cut bovine tibia into 2-inch chunks and pound out the cancellous bone (the spongy tissue in the center of the bone containing marrow and collagen) to produce their extracellular matrix hydrogel spray.

“These particles stick to the tissue you’re spraying it onto,” Keane explained. “Once the gel reaches body temperature, then it forms a gel that covers the injured tissue. This thin film prevents the contact of adjacent organs with the injured tissue. It’s that contact, actually, that causes adhesions.”

Not only does the spray prevent adhesions, but it helps accelerate tissue regeneration. The spray interacts with the immune cells and the repair cells to stimulate the healing process.

“Instead of getting a scar in response, you actually get a response that is functionally repaired and closer to the normal anatomy that it was before,” Keane said.

Based on an early study the team conducted in November 2019, the spray significantly reduced scar formation by 75 percent.

Currently, the standard approach to preventing adhesions is to use an implant called adhesion barriers, a thin translucent film made of biomaterial that physically separates tissue surfaces to keep them from touching. Repair cells are unable to penetrate the barrier and, therefore, allow the tissue surfaces to heal properly. Once the tissue heals, the barriers dissolve.

However, as robotic technology and minimally invasive techniques become more common in the operating room, TYBR’s spray is poised to have an advantage over the traditional barriers, which are more fragile to use and expensive.

“It’s like trying to place saran wrap with tweezers,” Smith said. “It’s like laying hundreds of dollar bills in the abdomen.”

Approximately 70 percent of abdominal and pelvic surgeries are done laparoscopically, but adhesion barriers currently on the market can only be implanted in open procedures, leaving a large population of patients with no other option than to develop scars that can lead to lifelong complications.

Future expansion

Adhesiolysis, a surgical procedure in which surgeons snip away at the messy web of adhesions to restore normal anatomy and organ function, is one of the top seven emergency general surgeries performed in the U.S.—along with laparotomy, large bowel resection, small bowel resection, operative intervention for ulcer disease, cholecystectomy and appendectomy procedures. According to a study published in BMC Surgery, more than 400,000 adhesiolysis procedures are performed annually nationwide, resulting in an estimated cost of $2.3 billion to the health care system.

“Sixty percent of all operations that occur are actually re-operations,” Keane said, adding that a majority of the repeats are due to an aging population. “The older people are, they probably had, at some point in their life, a surgery. That surgery caused scars or adhesions forming, keeping doctors in the OR for an extra 15 to 45 minutes, where they’re just spending time cutting away adhesions, which can cause complications, before they can even get to the reason that they’re there to do the surgery in the first place.”

By preventing adhesions from forming, TYBR Health’s hydrogel spray could alleviate the burden of hospital readmissions.

Although the team is currently targeting abdominal and pelvic adhesions, the hydrogel spray is a platform technology that could be expanded to include dermatology, plastic and reconstructive surgery (specifically breast reconstruction) and orthopedic surgery.

“In almost every tissue in the body, and every disease you can think of, there’s some aspect of scarring that affects the lives of millions and millions of people,” Keane said. “If you could affect a small percent of these diseases and these complications that lead to scarring, then you could have a massive effect on the way medicine is practiced in the world.”