The Narrative Practice Project: Journal-keeping at Memorial Hermann Northeast Hospital

A young man with a gunshot wound to the face walked himself into the emergency room at Memorial Hermann Northeast Hospital. The injury, which had shredded the tissue on one side of his jaw, left him unable to talk. But his eyes spoke volumes.

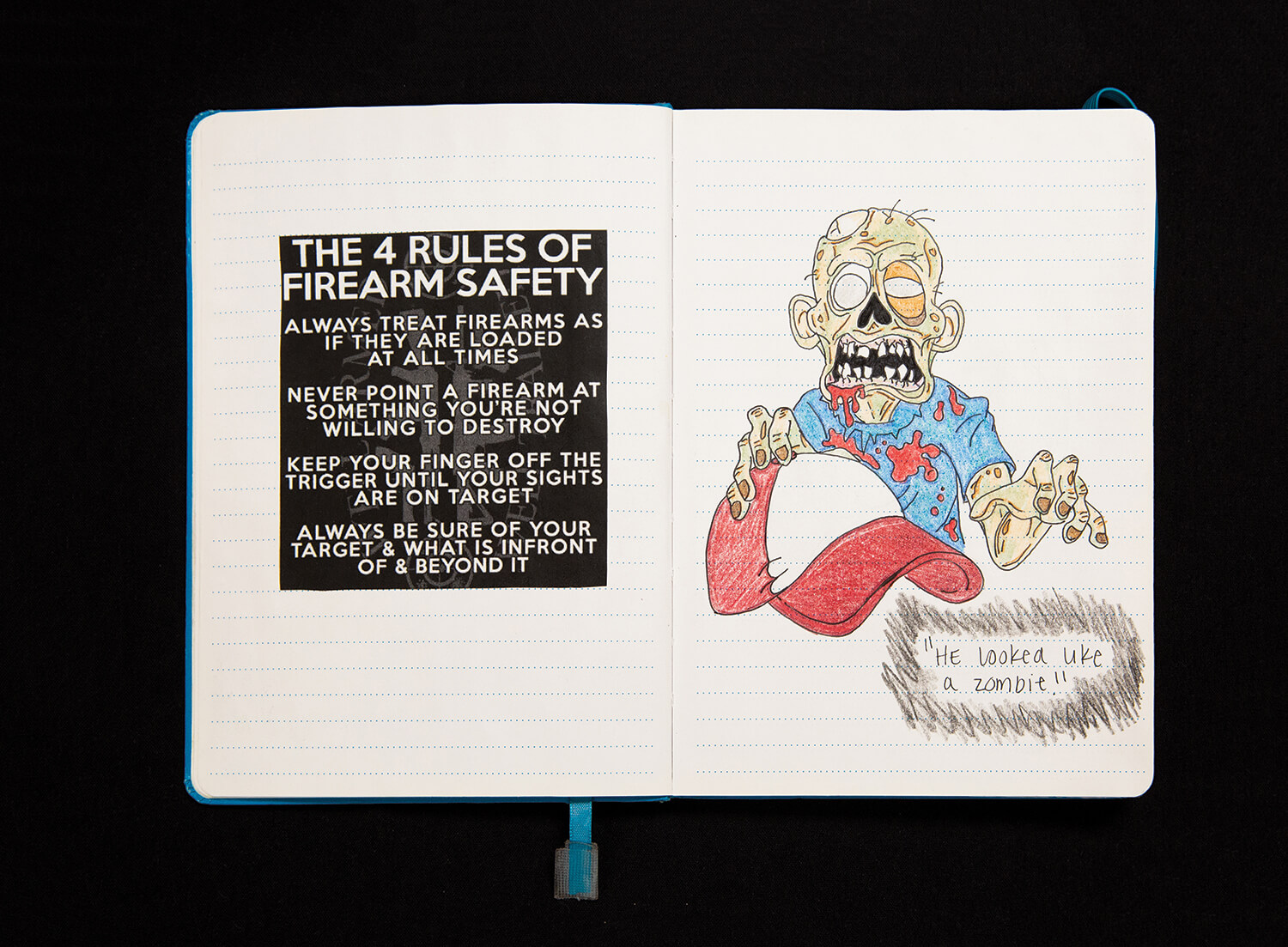

“He looked like he had costume makeup on—it was straight out of a movie,” said emergency department unit clerk Brittany Graves, who registers walk-ins, coordinates EMS traffic and initiates transfers. “He couldn’t say a word, but his eyes said, ‘Please, help me.’”

Emergency physicians did, indeed, help the young man, who survived his wound. But Graves couldn’t shake his expression and ghastly pallor. First chance she got, she drew a picture of him in her journal, pasting a printout of the four rules of firearm safety on the opposite page.

“I like my journal entries to feel like a completed art piece,” Graves said.

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Looking for the latest on the CORONAVIRUS? Read our daily updates HERE.

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Graves and other emergency department (ED) employees at Memorial Hermann Northeast are part of a narrative practice project launched by Stacy Nigliazzo, a nurse and poet whose most recent poetry collection, Sky the Oar, was published by Press 53.

“The emergency department is intense and fast-paced. You’re seeing people, a lot of times, on the worst day of their life,” said Nigliazzo, clinical coordinator of emergency services at the hospital. “I know what that does to me, how when I go home I carry it with me. Writing and art have always been my outlet, especially creative writing. And I see my staff get burned out; I see them suffering from compassion fatigue.”

Research shows that arts and humanities are essential to a robust medical education, because both disciplines encourage compassion and empathy, traits often lost within the crush and churn of medical care. Nigliazzo shared some of this research with her chief nursing officer, who gave her permission to launch an arts task force at the hospital. After a few individual projects, Nigliazzo passed out blank journals to staff members who expressed an interest.

“A journal entry can be one word,” she said. “It can be a picture. It can be a sketch. It can be something you cut out and pasted in. It’s intended to be something so you can remember what was important to you on this day—what you’ve endured, what you’ve earned.”

Cultivating empathy

Because the journals are whatever their owners want them to be, they can be wildly variable, from person to person and even from entry to entry within the same journal.

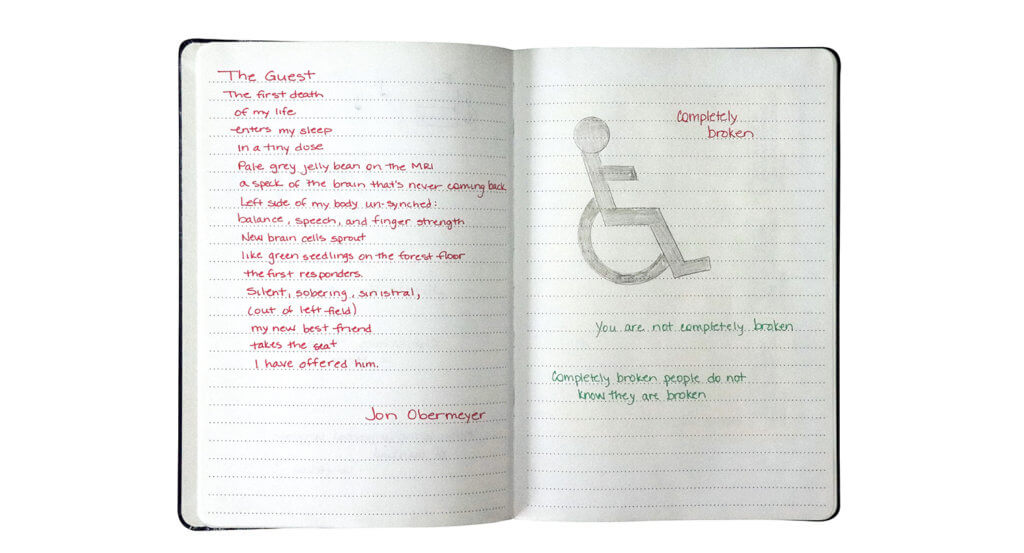

“I’m a reluctant journaler, so mine is not a daily thing,” said Lesa Thornton, an ED pharmacist at the hospital. “Over Christmas, I drew the symbol for a handicapped sign in my journal. I was arguing with my husband’s best friend, who had a massive stroke in September.

Because he is so young—50—he has recovered extremely well, but that is not how he sees it. He said to me, ‘I guess life goes on even when you’re completely broken.’ And I said, ‘You are not completely broken. Completely broken people do not know they are broken.’”

Emergency department pharmacist Lesa Thornton copied a poem about a stroke and drew a handicapped sign in her journal.

That last phrase made it into her journal, on the same page as her drawing of the handicapped logo. On the opposite page, Thornton copied a poem longhand by writer and stroke survivor Jon Obermeyer that leans toward the positive: New brain cells sprout/ like green seedlings on the forest floor/ the first responders.

Another journaler has kept to a specific theme. D’Ann Bailey’s journal is devoted entirely to her own health story, which took a dramatic turn more than a year ago when she was diagnosed with breast cancer.

“I decided to write down the journey, not only for me to kind of get it down on paper, but for my children to look back,” said Bailey, a patient experience nurse navigator who works bedside with patients and meets with staff to ensure that patients’ needs are being met. “This morning, I grabbed the journal on my way out the door and started flipping through. In here is not only the journey, but lists of the people who brought food, the people who sent cards and gifts. The time I cried for two days straight. … I’m so grateful I can go back and remember.”

Nigliazzo’s journaling project springs from a broader movement in medicine that took formal shape a few decades ago, when universities and medical institutions began to launch narrative medicine degrees and programs. Narrative medicine emphasizes storytelling skills—listening, observing, interpreting, reporting, writing—to improve care and provide a necessary outlet to both patients and caregivers.

The mission of the famed narrative medicine program at Columbia University, a mother to all others, is to “fortify clinical practice with the narrative competence to recognize, absorb, metabolize, interpret, and be moved by the stories of illness.” Columbia offers a Master of Science in narrative medicine.

In Houston, Baylor College of Medicine’s narrative medicine program brings together faculty from diverse disciplines across the Texas Medical Center and hosts reading and writing events.

‘It leaves an imprint’

At Memorial Hermann Northeast, the journals have become a way for employees to reflect on their most difficult moments. The journalers agree that once you stand over death with a co-worker, something in your relationship changes. Those are the types of situations often captured in the journals.

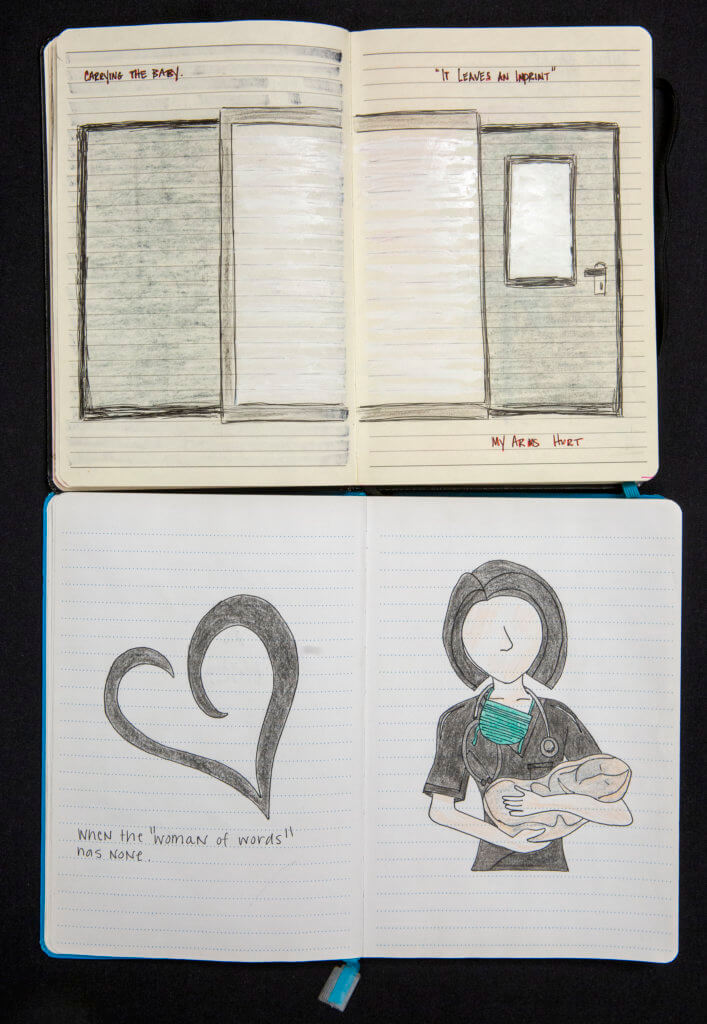

Nigliazzo and Graves created separate journal entries about the same poignant incident.

Top: Nurse Stacy Nigliazzo drew morgue doors in her journal after carrying a deceased baby there. Bottom: Unit clerk Brittany Graves drew a picture of Nigliazzo on her way to the morgue with the baby.

“There was a situation where an infant had died,” Nigliazzo began, “and when an infant dies in the hospital, the nurse wraps them in a blanket—completely covering everything—and carries that child to the morgue. They have a cart for adults, but for babies, they don’t. The nurse carries them. I can never bring anyone else on my staff to do that, so I always do it. And every time I go, after I’ve taken a baby there, my arms always hurt, even though these babies weigh practically nothing. On that day, I took a picture of the morgue doors and made a note that my arms hurt. I also wrote down something the security guard said when she unlatched the morgue doors for me. She looked at me and said, “’It leaves an imprint.’”

Graves was clerk that day. When Nigliazzo shared her journal entry—a pencil drawing of the morgue doors and the quote from the security guard—Graves immediately recalled that baby, that day. And Nigliazzo’s silence.

“I remembered what Stacy looked like when she walked out of the room on the way to the morgue,” Graves said. “She had no face. No expression.”

Graves drew a picture of her co-worker in her journal, holding the baby who was fully swaddled in a hospital blanket. In the sketch, Nigliazzo’s face is almost blank. Graves wrote: “When the ‘woman of words’ has none.”

Nigliazzo hopes to expand narrative medicine at Memorial Hermann by launching a formal narrative practice curriculum within the nursing residency program. So many nurses, she said, struggle early on and even quit because of burnout.

“I’m trying to get them at the beginning of their careers— to get them a wellness tool early,” Nigliazzo said. “It helps with empathy, observation, to engender curiosity and appreciate ambiguity. We want nurses and other people to be curious about what’s going on and to be comfortable asking questions.”