Texas Medical Center experts assess community health two years after Hurricane Harvey

Two years after Hurricane Harvey—the wettest tropical cyclone to hit the United States—made landfall in Houston, medical experts, community leaders and researchers gathered at Baylor College of Medicine to discuss health efforts that were initiated during and after the storm.

During the Hurricane Harvey: 2 Years After symposium, attendees were welcomed by Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner, former Harris County Judge Ed Emmett and clinicians. The forum was also greeted by researchers from the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston (UTMB Health), Rice University, Oregon State University, The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston School of Public Health, the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and the Environmental Defense Fund who discussed research and care initiatives instituted during and after the storm as well as milestones and lessons learned.

“We have a long history at Baylor of providing medical care post-disaster,” Baylor College of Medicine President Paul Klotman, M.D., told the audience. “We really mobilized our physicians and in the first two or so days, we provided … medical care and psychiatric care for an extended period of time.”

Baylor College of Medicine physicians and students staffed the George R. Brown Convention Center, which became the temporary home to 10,000 Houstonians displaced by the storm.

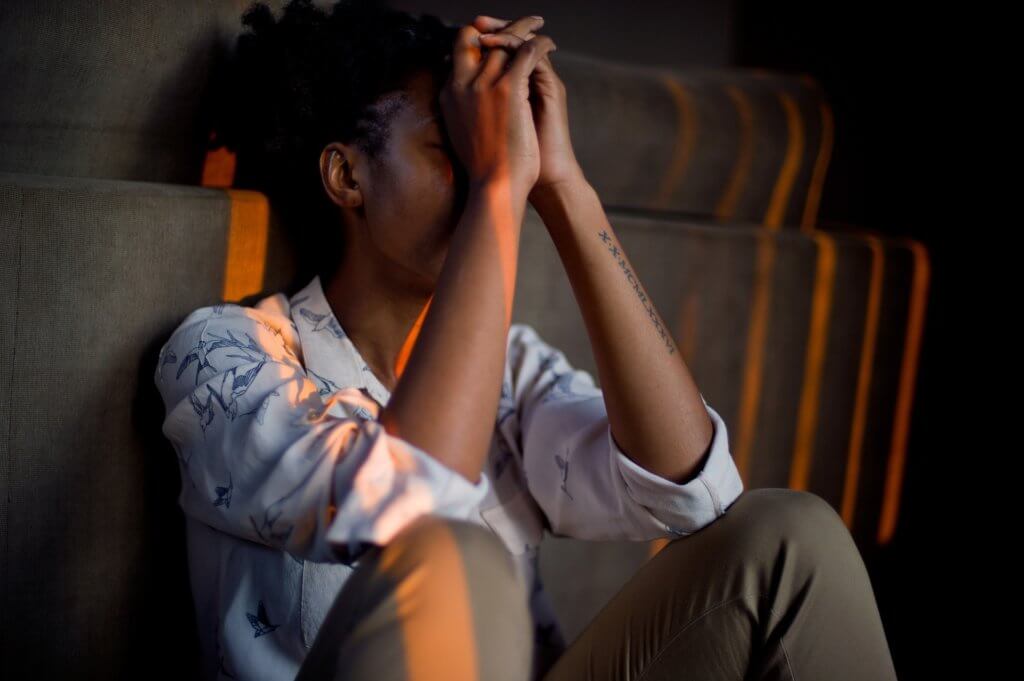

Cheryl Walker, Ph.D., director of Baylor’s Center for Precision Environmental Health, became emotional recounting the days after Harvey hit Houston.

“When it was gone from Texas, there were 103 deaths, a lot of damage, thousands were displaced. It was absolutely devastating,” she said. “It is remarkable to think 25 to 30 percent of Harris County was submerged as a result of Harvey.”

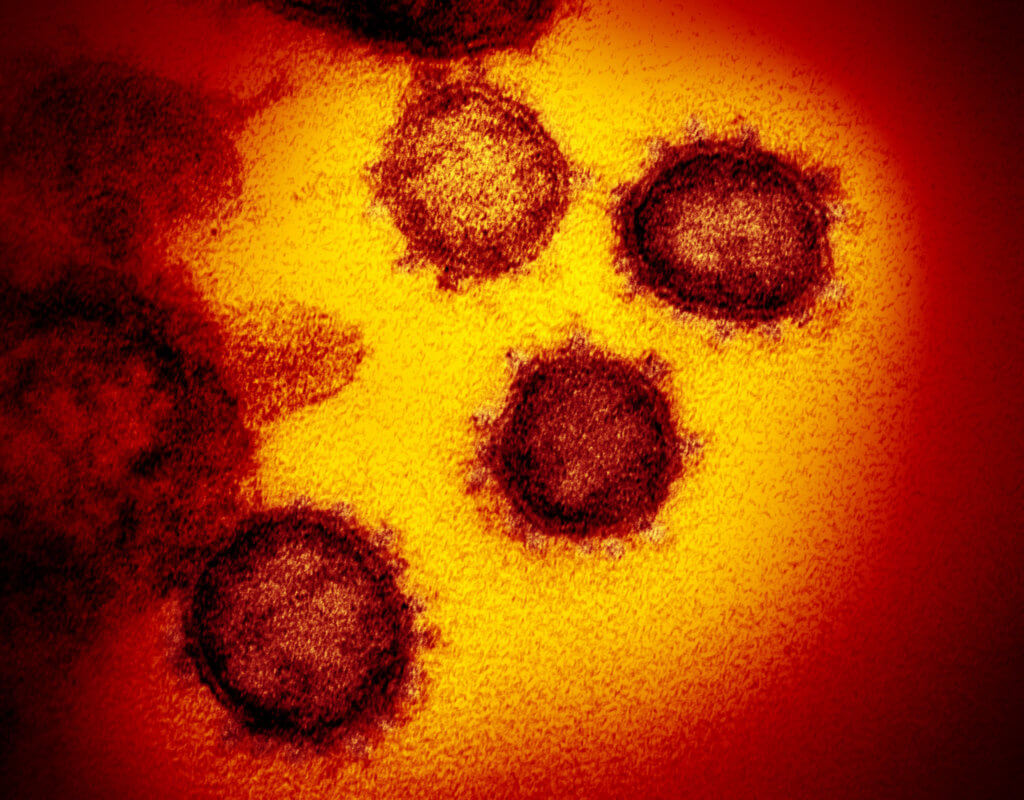

Walker and a team of researchers from Baylor, UTHealth and Oregon State developed the Houston Hurricane Harvey Health Study in the days following the storm to track the chemicals to which residents had been exposed. To do this, they enrolled people living in four different parts of the area—the Addicks community in northwest Harris County, Bellaire/Meyerland in southwest Harris County, East Houston and Baytown in far east Harris County on the Houston Ship Channel.

“We understood that if we didn’t get out in the community immediately after the wake of the storm, we would miss the opportunity to find out what people were being exposed to as a result of the flooding, drainage and remediation and cleanup work.”

Researchers enrolled 208 participants from Harris County and tracked their toxicity levels with waterproof wristbands worn continuously for seven days.

Baylor assistant professor Deborah Hyink, Ph.D., participated in the wristband study after her home flooded.

“I was interested in knowing what we had been exposed to,” she said. “When that floodwater came in, it stripped all of the varnish and stuff off of the wood furniture and we got exposed to it. … You just don’t know what you are in.”

The wristbands measured for more than 1,500 different chemicals. For this study, researchers focused on pesticides, pharmaceutical chemicals, industrial chemicals, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), endocrine disruptors, dioxins and furans, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), flame retardants and personal care products.

On average, 26 chemicals were found in each wristband, Houston Hurricane Harvey Health Study researchers shared. They detected 183 chemicals out of the 1,500 and no dioxins or furans.

“Doing this study really changed our lives—living in Houston and understanding all of the things that have happened,” said Melissa Bondy, Ph.D., professor and section head of epidemiology and population sciences in Baylor’s department of medicine. “Within days after the hurricane, we were on the ground. … We are not disaster researchers, but we came together because this is what we had to do.”

In addition to hearing from other care providers and researchers from around the Texas Medical Center, Klotman honored Turner and Emmett for their leadership during the storm with Baylor College of Medicine commemorative coins.

In turn, the mayor bestowed a City of Houston proclamation to recognize the work by the health care community during Harvey.

“In the midst of all of that water, the best of our region stepped up,” Turner said to the audience. “Although the debris is off the ground, we are still monitoring the emotional and physical impact of that storm on adults as well as kids, so thank you all very much.”