‘I’m Dr. Red Duke’

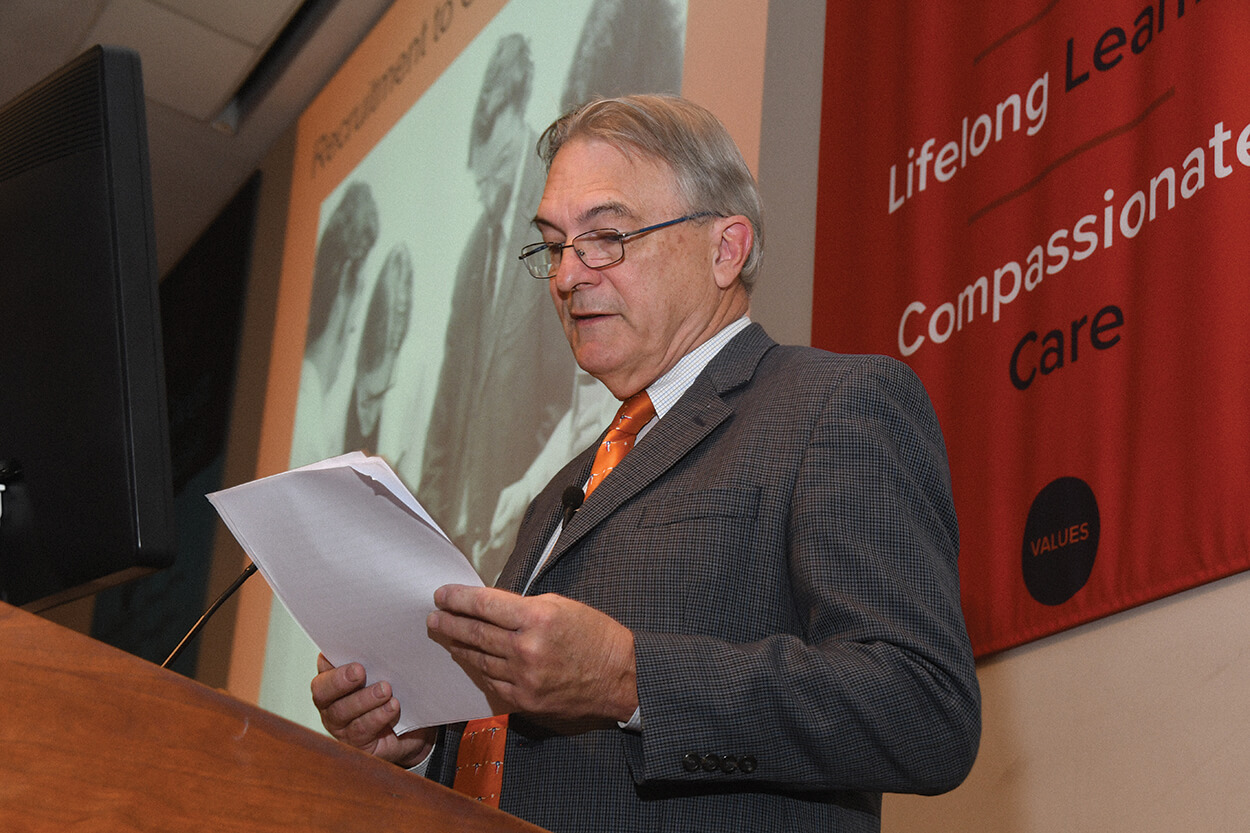

The late James H. “Red” Duke Jr., M.D., was a Texas original. A trauma surgeon at The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth) and Memorial Hermann, Duke also launched Memorial Hermann’s Life Flight program and appeared in a popular nationally syndicated television spot in the 1980s and ’90s. In his recent book, I’m Dr. Red Duke, Bryant Boutwell, a former professor at UTHealth’s McGovern Medical School, examines the man behind the legend.

Excerpt:

Working with Red Duke always involved a few hidden sermons on patient follow-through and perseverance. More than a few of his surgical students remember his Duke-speak directive: “You take them, you raise them.” For the students who responded to his stock question, “Who’s the most important person in this OR?” by answering “the surgeon” rather than “the patient,” a reprimand that would make Red’s irascible father proud was soon to follow. Linda Mobley, a veteran nurse who worked beside Red for years, recalls, “I’d see the new residents tell Dr. Duke that the surgeon was the most important person in the room and just cringe behind my mask as he spared no mercy reprimanding [them]. Working with Red was always, without compromise, giving your best and putting your patient first.”

Tank commander Lt. James Duke Jr., Texas A&M University.

In surgery Red could entertain, teach, and pontificate on the problems of the world without missing a beat on the procedure at hand. Country music might be playing and the atmosphere relaxed, but he was dead serious when it came to attention to detail.

His Seldin training in internal medicine [Donald Seldin, M.D., was a mentor of Duke’s] married to practiced skills with the scalpel gave him a reputation for saving patients others considered beyond hope. He could bark at a team member and call someone out in strong language when occasion arose, but generally he approached the teachable moment with a constructive message.

Many veteran surgeons marveled at his ability to work long hours, far longer than most. One surgery stands out as his longest—fifty-four hours. “Yes, fifty-four hours without sleep.” The procedure was not typical, fortunately. The victim was a deputy constable serving papers on a member of the criminal element in Houston when things went wrong.

And somebody shot him right here with a shotgun [pointing to his belly button]. His belly was full of green stuff. I honestly believe that guy had eaten a quart of guacamole. And it hit the vena cava and his duodenum and pancreas—bad injury. So, hell, what do you do? And then when you have a pancreas and duodenum that messed up, and you take that out—you take out the duodenum, the head of the pancreas, and then you’re supposed to put it all back together so that the bile drains into the jejunum. . . . And because he was so contaminated, I decided to remove his entire pancreas which is not that hard to do, [but] if that connection between the pancreas and the jejunum leaks, you got a mess.

In telling the story Red was lost in the moment, describing intricate details of the epic procedure while simultaneously sketch-ing on a napkin his approach and multiple complications along the way. Clearly he was not going to give up on his patient and did not (the patient survived, as best he remembered). Why attempt such a long procedure? “Yes, that’s crazy, but there wasn’t anybody else to do it.”

The cover image from Bryant Boutwell’s biography, ‘I’m Dr. Red Duke.’

For many procedures, improvisation and bucking the status quo were not out of the question. Afghanistan, the army, and the Boy Scouts had taught him that if you don’t have what you need, you make do. For years Red’s surgical residents would hear him preaching during surgery on the value of leeches and maggots for cleaning wounds and brown sugar to promote healing. One surprised resident was sent from the operating room to the grocery store during a long surgical procedure to buy additional brown sugar. “Brown sugar, not white sugar,” Red yelled out the door as his student headed for the store scratching his head. It worked time after time, and Red rejoiced in proving his point. He also pointed to support in the medical literature for the position that alternative medicine should not necessarily be dismissed out of hand.

Looking back, Red summed up his teaching career with satisfaction. “I’ve had some really great students over the years, and I can proudly say not a one was taught to do half a surgery or to think of anything beyond the patient as the focus of everything we do.”