Can our muscles stay young even as we get old?

We lose muscle as we get older. Period. No matter how much we exercise or diet, age-related muscle loss is a fact of life.

Our strength typically tops out around age 35 and then starts to decline—slowly, at first, but accelerating in our later years.

“Think of your parents at age 75,” said

Stanley Watowich, Ph.D., an associate professor in the department of biochemistry and molecular biology at The University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB) at Galveston. “They’re about half as strong as they were when they were 35. That limits their quality of life. Maybe they can’t lift the grandchildren. Maybe they have trouble walking.”

Watowich wants to change that. He and his team are developing a drug, now known as RT-001, to help people retain muscle strength as they age—a pill that would allow our muscles to act younger even as we get older.

“We know we really decline at 60,” Watowich said. “But can we change that trajectory? If we can, you’re going to stay stronger as you age. You’re going to have a better quality of life.”

This holy grail of health works by targeting one enzyme in the body.

“There is a molecule—an enzyme—that controls how metabolism occurs in different cell types,” Watowich explained. “As we age, this enzyme increases in the muscles. We don’t know why, but it does, and it interferes with the muscle stem cells’ ability to become activated. When you’re younger, muscle stem cells get activated, go to damaged muscle, proliferate, grow and fuse and they repair the muscle. As you age, you still have these stem cells, but they no longer get activated, in part because the metabolic state has been impacted by this enzyme, called nicotinamide N-methyltransferase (NNMT).”

Watowich’s drug turns off NNMT. “By stopping it from working,” he said, “we kind of reset the stem cell to a point where it functions as if it’s in a younger person.” Results from a study of the drug’s effect on aged mice were published earlier this year in Biochemical Pharmacology.

Watowich and his team showed that in older mice treated with the drug, muscle fiber size and muscle strength nearly doubled. In addition, no adverse effects of the drug were found.

Watowich has been working on RT-001 for three years and it will be at least another four, he estimates, before it is released to the public. More testing is yet to come.

“The idea is to see how much compound you can give clinical models over a month-long period,” he said. “You’re looking to make sure you’re not causing problems and you want to establish an upper dose.”

The drug does not mean that adults get a pass on eating well and exercising, he asserted. The pill will be more effective for people who take care of their bodies.

“Our drug actually stimulates the stem cells and allows them to repair injured muscles,” Watowich said. “It’ll work better the more you work the muscles, but it’ll even help maintain daily activity.”

Activity, drugs, nutrition

Physical activity and diet play a vital role in protecting muscle health. In the department of nutrition and metabolism at UTMB, Doug Paddon-Jones, Ph.D., studies how to retain muscle strength and how to consume proteins to help with this process.

Doug Paddon-Jones, Ph.D., the Sheridan Lorenz Distinguished Professor in Aging and Health at UTMB, researches muscle mass and function in healthy and clinical populations.

“In the best-case scenario, once you hit 35 or 40, depending on how well you’ve looked after yourself, you lose a little bit of muscle each year,” Paddon-Jones explained. “It’s insidious and slow. From age 40 to 60, you can make up for it with subtle lifestyle changes. Even though you are losing a little bit, your body fat tends to slide up around the same time, so bathroom scales are useless. Your body weight may not change, but body composition is starting to go in a pudgy direction.”

Paddon-Jones and his team have done several bed rest studies, mimicking the inpatient experience in hospitals, to examine the loss of muscle from inactivity and sarcopenia, which is age-related muscle degeneration.

“Some folks on bed rest, the muscle just falls off them,” Paddon-Jones said. “Other people are kind of resilient. From a practical perspective, intervention should be geared to a worse-case scenario, because even if you’re resilient now, you may not be your entire life. ”

He advises protecting muscle from a young adult age, because its loss tends to sneak up on people.

“If you want to protect your muscle health, your function, your glucose and metabolism from the ravages of age, inactivity or disease, you’ve really only got three options: exercise, drugs and nutrition,” he said. “In my mind, it’s nutrition that you have to optimize for any of these other areas to work optimally. We want to get patients out of bed, but there’s a risk and a cost associated with that. Same with drugs—they can work, but not for everyone. But we absolutely have to feed every single person, so why not tweak that? You’ve got to eat, but you’ve got to be pragmatic and efficient about it.”

One option for building and repairing muscles is the amino acid leucine, one of the most abundant amino acids in protein-filled foods. Some of Paddon-Jones’ bed rest studies have examined leucine’s effect on the body.

“Leucine is one of the essential amino acids, one of the building blocks,” he said. “It’s special because it serves as a trigger or a switch that turns on the molecular pathways that build and repair muscle. The optimal thing is to turn it on every now and again—little bouts where you increase the leucine.”

Results from bed rest studies have shown that leucine can safe-guard against some muscle loss. An average middle-aged man lost about two pounds of muscle from his legs after just one week of bed rest, Paddon-Jones said. But the group that received leucine—four grams delivered three times a day in powder form, for a total of 12 grams daily—fared better.

“The group we gave leucine to, over the first seven days, lost half as much muscle,” Paddon-Jones said. “It has a short-term protective effect. And 12 grams a day? That’s a really small amount.”

Instead of buying leucine as a supplement in a health and wellness store, integrate it into your diet, he added. “If you ate five ounces of beef, you’d get about three grams of leucine,” Paddon-Jones said. “In a glass of milk you’ll get a good amount, as well. So you shouldn’t buy it. Eat some food. And once you’ve turned on the muscle building machinery and put the protein there to provide all the building blocks, it’s on.”

Human trials

Watowich plans to start testing RT-001 in humans in late 2020.

“By next year, quarter four, we will have filed with the FDA a document showing all the safety studies, all the efficacy studies, how we’d manufacturer it, and so on,” Watowich said. “We’ll begin human trials quarter four of next year.”

Watowich holds a sample in his lab.

The first six months of human trials will analyze how the drug behaves in the body, starting with a small dose. If there are no problems, Watowich and his team will increase the dose to the level they think will be the treatment.

“The first study is done with about 40 patients—very small,” Watowich said. “We will add a cohort of a group of about 12 elderly people, individuals aged 55 to 70, because as you age you can run into renal problems.”

Then, toward the end of 2021, they’ll begin an efficacy study of about 300 patients aged 55 to 75—“healthy, normal people,” Watowich said, “not gym rats or marathon runners.”

With this larger group, the scientists are looking for answers to specific questions.

“What we’re asking is, if you go to the gym and you take this pill, will you get much stronger?” Watowich said. “Instead of increasing your strength by 15 percent, can we get you up to 25 percent, 30 percent, 50 percent stronger? We know in mice they almost double their strength. We don’t expect to double the strength of elderly people, but can we get them significantly above what would happen if they would just go to the gym?”

If all goes well, the team will then study hip fracture patients recover-ing from surgery to see if the drug can accelerate recovery. “In a six- to nine-month trial, can we make post-hip fracture patients stronger such that they survive, thrive and return to independent living? Only a small fraction of elderly with hip fractures ever return to independent living,” Watowich said.

If the team hits all these milestones, the drug could be available by the end of 2023. Collaborators on RT-001, which will get a snappier name before it goes to market, include colleagues from UTMB; Chris Fry, Ph.D., formerly of UTMB and now associate professor at the University of Kentucky’s College of Health Sciences; Nicholas Young, Ph.D., an assistant professor of biochemistry and molecular biology at Baylor College of Medicine who will be doing some epigenetic profiling; and researchers at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, who will be analyzing tissue samples.

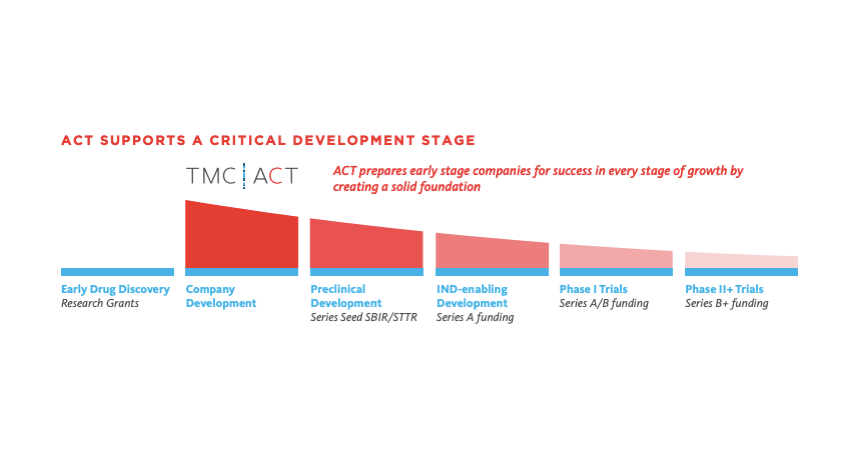

In addition, Watowich has spun out a biotechnology company, Ridgeline Therapeutics, housed at JLABS @ TMC, to develop drugs to reverse Type 2 diabetes, obesity, muscular dystrophies and sarcopenia.

One day, Watowich’s drug could benefit everyone over a certain age.

“If everything works, you start taking the drug at 40 and you keep up an exercise program—you stay active,” he said. “If you do that, you’re not going to have as many diseases that affect you in terms of cardiovascular health.”