“As a clinician, you feel the tremors of COVID. … You have to train yourself to do less and observe more.”

Ricardo Nuila, M.D., is a hospitalist and teaching attending physician affiliated with Ben Taub Hospital and Baylor College of Medicine. He spoke with TMC News on April 13, 2020.

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Looking for the latest on the CORONAVIRUS? Read our daily updates HERE.

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

As a clinician, you feel the tremors of COVID. It’s not a linear course, like what you expect when giving antibiotics to a patient for an infection. With COVID, the oxygen level goes down a bit and then you don’t know where it’s going to go from there. The patient gets a little bit better one day and you have hope. Then the next day things regress and you think, ‘Wait a minute. No.’

The first COVID-19 patient I saw must have been three or four weeks ago on a night shift.

One of the particularities of hospital medicine and hospitalists is that we admit patients from the emergency room and we’re the people responsible for those patients up until they require a ventilator. I think the stats show that for every person who goes to the ICU [intensive care unit] there are two or three patients who are managed by hospitalists on the floors. So it’s really one of those situations where you want to be the only doctor a patient sees, because if that patient sees other doctors it’s usually ICU doctors and that means that things have taken a turn for the worse.

And here’s the thing: The doctor is in a privileged position. The doctor sees the patient and then writes orders and those orders are implemented by other people. So the doctor manages how much exposure there is to COVID in the hospital. All orders engender more exposure, so you have to weigh all of your choices really carefully. COVID causes you to be as efficient a diagnostician as possible.

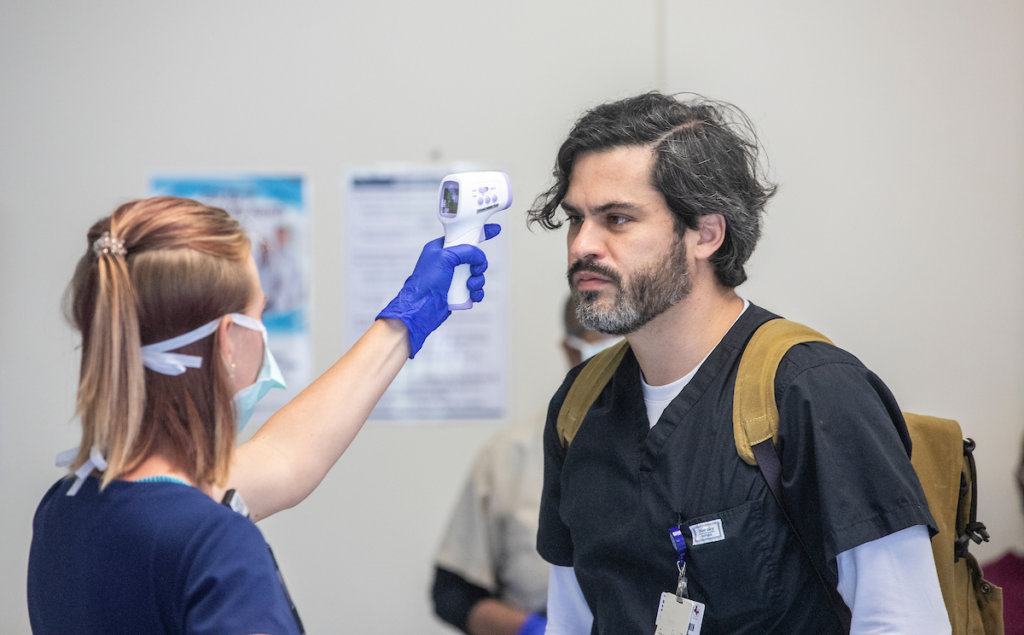

Ricardo Nuila, M.D., has his temperature taken in the entryway of Ben Taub Hospital before beginning his shift.

There was one patient at Ben Taub, she had a week of sudden onset cough and she was clearly short of breath—oxygen levels low. The COVID test came back negative, but we know there are false negatives and you just have to reckon with that. Are you going to push for a different diagnosis? There came a point where I had to say, ‘Let’s look for something else.’ We did find something else and it was an even worse diagnosis than COVID. Those are the difficulties we face.

This pandemic has put a premium on patience. We don’t have any known therapy against COVID and I think there’s an inclination in all doctors to feel unsettled by not giving certain treatments or by not actively trying to solve an illness. Patients can be on oxygen in the hospital for a while and you can’t bring them off of the oxygen. This illness can just linger. I think physicians need to ask themselves: Can I be patient? Is the breathing getting better or is the breathing getting worse? Can we wait another day before sending the patient to the ICU, where they may need to be put on a ventilator? If we’re not worsening, can we just continue to keep doing the same thing?

Ordinarily, the health care environment is about getting things done and getting things done quickly. With COVID, you have to train yourself to do less and observe more. It’s an era of uncertainty and that has made being a doctor very difficult. So much of medicine is built on levels of certainty.

You’re also not using your tools as much. I don’t use my stethoscope as much because it’s a potential source of infection. There’s a limited amount of disposable stethoscopes, so, again, that just adds to the uncertainty.

After Hurricane Harvey, I went to care for some of the displaced at the George R. Brown Convention Center pretty early on, when we just didn’t know how many people would be coming in. You saw people who were shivering. You saw people who were still wet from being rescued from the water. At that point, before we had a plan to get people medications and tell them where to go, the best you could do was reassure them, to say, ‘You’re OK without your blood thinners for one day.’

In that way, COVID is similar. One of my COVID patients told me he always felt good when we spoke. That made my day because, other than the oxygen, the most that I could give that person was my attention and my words. But that’s also the case with everybody in the hospital right now because there are no visitors. Even with non-COVID patients, you have to be aware that they are alone. I had a patient who was elderly and awaiting major surgery and she’s there, alone, without her family. She’s a non-COVID patient, but it’s the same. So your job expands. I’ve always felt like this was part of the job, but I feel like it’s all the more important right now to focus on making the patient feel like they have an ally within the hospital walls because they can’t have the physical contact with people they love and rely on for decisions.

Another surprising thing is just how differently different doctors and nurses interpret new information. It feels like everything is confirmation bias right now. Let’s say a new COVID study comes out and it doesn’t clearly point in one direction or another. Somebody thinks about it and says, ‘Well that reinforces what I previously thought about COVID.’ Everything is so scattershot that people are just using whatever is written out there to confirm their own preconceived ideas about illness and philosophies of medicine. For instance, hydroxychloroquine is a malaria drug that’s being considered as a treatment for COVID. There’s a French study that came out and the people who want to believe in hydroxychloroquine will take something positive out of it, and the people who don’t want to believe in it will take something negative out of it. Science takes time and we’re forcing science to produce answers too quickly.

That’s why I really believe we should be focusing on the person in front of us as much as possible, because if you start to think about all of what’s written right now, you’ll just go crazy.

It’s an interesting time to be a doctor at a safety net hospital because there’s a clear message with COVID, which is: Save as many patients as possible. Save them all. America does not usually send that message clearly. In a health care environment with so many uninsured people, there are conflicting messages and questions, such as: Should people be receiving health care if they’re not insured? There’s something relieving about treating COVID patients because you know your job is just to do the best that you can.

—Ricardo Nuila, M.D., as told to TMC Pulse editor Maggie Galehouse