How scientists are responding to the novel coronavirus

The highly contagious respiratory illness caused by a novel coronavirus originating in Wuhan, China, has infected more than 80,350 people and killed more than 2,700 as of late February, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). At this point, the continued spread of the coronavirus seems inevitable.

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Looking for the latest on the CORONAVIRUS? Read our daily updates HERE.

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

This virus “shares some similarities with other known viruses, but it’s new to science,” said James Le Duc, Ph.D., director of the Galveston National Laboratory at The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston (UTMB), one of the country’s largest active biocontainment centers on an academic campus

Scientists currently know of seven types of coronaviruses, including the 2003 Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARSCoV), the 2012 Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS-CoV) and, now, the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19).

The novel coronavirus and the SARS coronavirus are the most similar, sharing 80 percent of the same genes, said Peter Hotez, M.D., Ph.D., dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine and co-director of the Texas Children’s Hospital Center for Vaccine Development.

After the SARS outbreak, several Texas Medical Center institutions collaborated with centers in New York and China to develop and manufacture a SARS vaccine, with funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The team included Baylor College of Medicine’s National School of Tropical Medicine, Texas Children’s Hospital Center for Vaccine Development, Galveston National Laboratory at UTMB, New York Blood Center and Fudan University in China.

“When this new epidemic came out, we quickly learned from Chinese scientists that both viruses bind to the same receptor,” Hotez said. “We think there’s a good possibility that the vaccine that we were funded by the NIH to develop here in the Texas Medical Center may actually work against the epidemic.”

What is a coronavirus?

The first cases of the novel coronavirus were reported to WHO on Dec. 31, 2019. The virus has since spread to countries outside of China, including Thailand, Vietnam, South Korea, Malaysia, Japan, Australia, France, Germany, Cambodia, Sri Lanka and the United States—prompting major cities in China to be placed under partial or full lockdown and airports across the world to screen for possibly infected passengers.

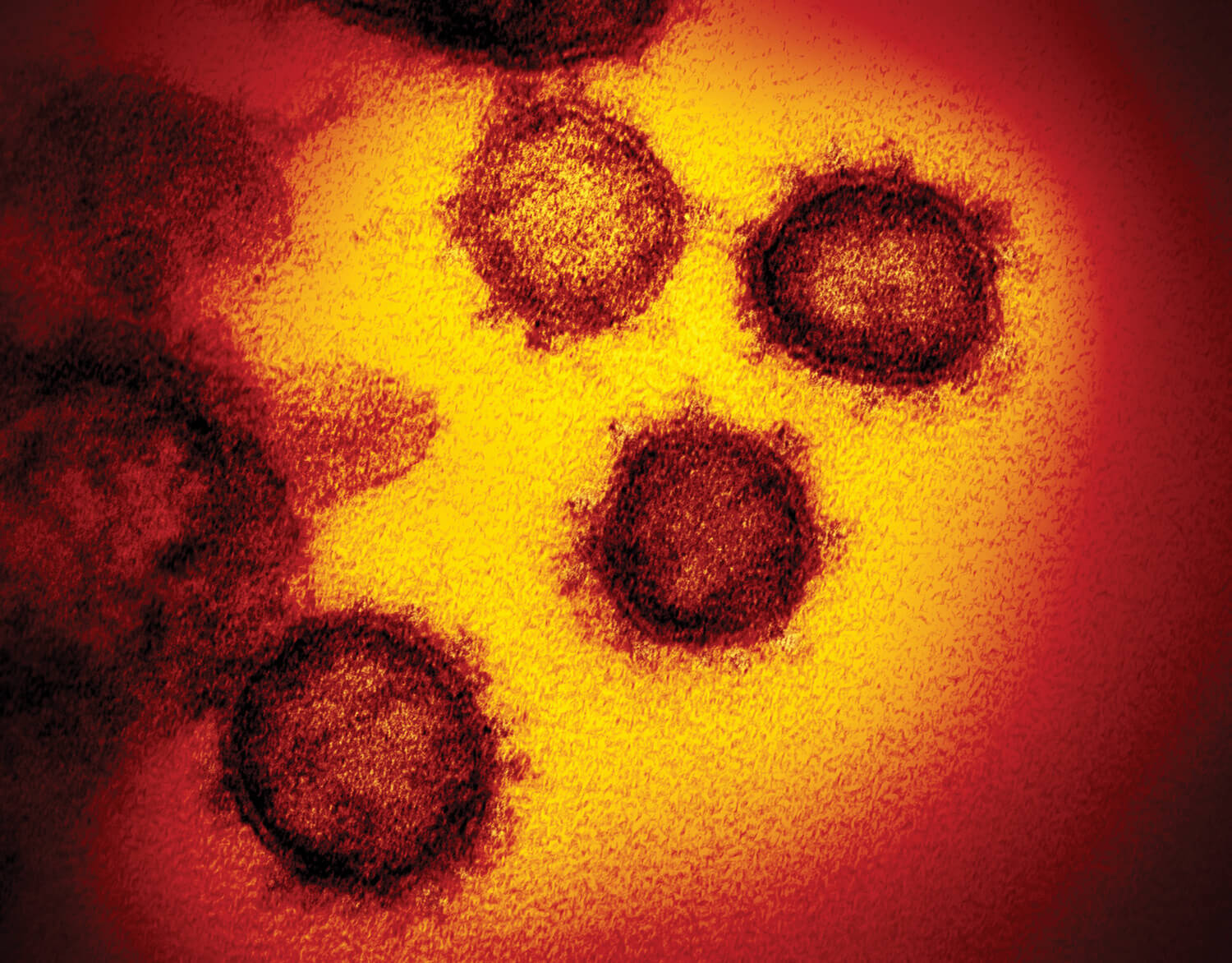

Coronavirus is an umbrella term for a large category of zoonotic viruses transmitted between animals and people, causing respiratory illnesses that range from the common cold to severe disease. Named for their resemblance to the outer atmosphere of the sun, coronaviruses have crown-shaped spikes protruding from their surface.

Coronaviruses enter the respiratory tract through the nose and have an incubation period of approximately three days. Common symptoms include fever, cough, shortness of breath and difficulty breathing; however, patients with more severe conditions can experience pneumonia, severe acute respiratory syndrome, kidney failure and death.

Currently, there is no antiviral drug to effectively treat the coronavirus.

“It’s all supportive care today,” Le Duc said. “Once we get access to the live virus, we can then test in animal models if antiviral drugs or other therapeutic interventions would help reduce the disease burden. I think that’s a critical next step.”

How have we prepared for this outbreak?

After the 2003 SARS outbreak that infected more than 8,000 people and killed 774, the WHO worked with nearly 200 countries to implement the International Health Regulations 2005, measures designed to bolster disease detection and surveillance of international ports, airports and ground crossings.

In addition, the Obama Administration signed an executive order in 2016 to advance the Global Health Security Agenda, an international initiative to protect against infectious disease threats.

As a result, the government established a “strategic national stockpile” of preparedness, Le Duc said.

“The country as a whole has invested heavily in preparedness for all sorts of disasters—natural disasters, as well as infectious disease outbreaks,” Le Duc added. “The government has on hand a lot of resources that could be used to help respond to an outbreak.”

At this stage, though, focusing on developing therapeutics to treat the coronavirus as opposed to a vaccine will probably have the greatest immediate impact, Le Duc said.

“We’re too reactive,” Hotez added. “We wait for the crisis to happen and then we scramble and try to put Humpty Dumpty back together again, but vaccines don’t work that way. Vaccines require weeks or months of safety testing. That’s the problem by staying in reactive mode.”