Adult-onset food allergies: More common than you think

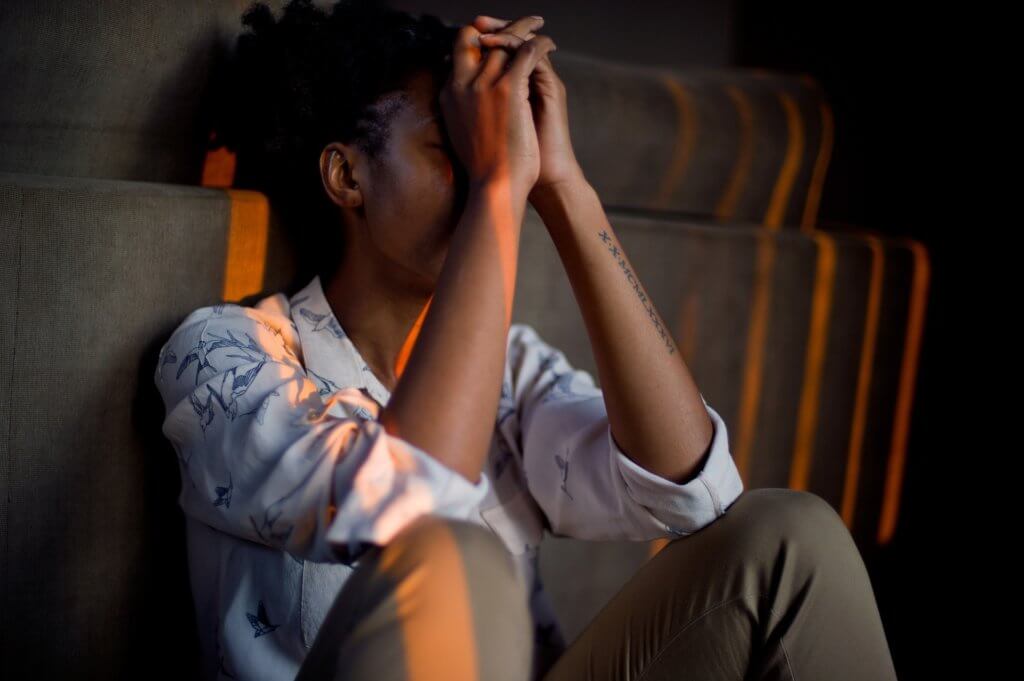

In June 2011, 22-year-old graduate student Amy Barbuto sat down at a Thai restaurant in Houston with her boyfriend and family, ready to enjoy pad thai and fried rice. She asked that her dishes be prepared without gluten because gluten upset her stomach, but when the restaurant accidentally used the wrong soy sauce, her throat began to swell and she started to suffocate. She was in anaphylactic shock.

“We didn’t really know what was going on because it had never happened before,” said Barbuto, who was later diagnosed with a severe allergy to wheat and gluten. “The first time’s always scary.”

She was rushed to the hospital, where doctors pumped her system with a cocktail of anti-allergy drugs—epinephrine, Benadryl and albuterol—and placed her on a ventilator that pushed air into her lungs for the next 12 hours.

“It was surprising,” Barbuto said of her diagnosis. “I grew up eating [wheat and gluten] and I used to be normal, so it’s weird how you can develop something like this later in life. You can eat something your whole life and be fine and then, all of a sudden, your body won’t let you eat it anymore.”

Contrary to popular belief, adults with no history of food allergies can unexpectedly develop them. In a survey of more than 40,000 adults published recently in JAMA Network, researchers from Northwestern University and Stanford University found that nearly half of adults who reported being allergic to a certain food or ingredient developed the allergy in adulthood. Nearly 11 percent of adults reported having a food allergy, with adult-onset food allergies representing half of those cases.

These findings, researchers said, suggest that adult food allergies are more common than previously believed and tend to be more severe compared to allergies developed during childhood.

Unfortunately, for Barbuto, many food items contain wheat or are produced in a facility with wheat products. She has been hospitalized for allergic reactions 25 times since she was diagnosed in 2011.

“It’s a hard one to avoid, even when you work your hardest to avoid it,” she said. “My allergy is so severe that I could get exposed and not even know it. My food can look gluten-free, look normal … but all it would take is somebody having touched bread and then touched my plate.”

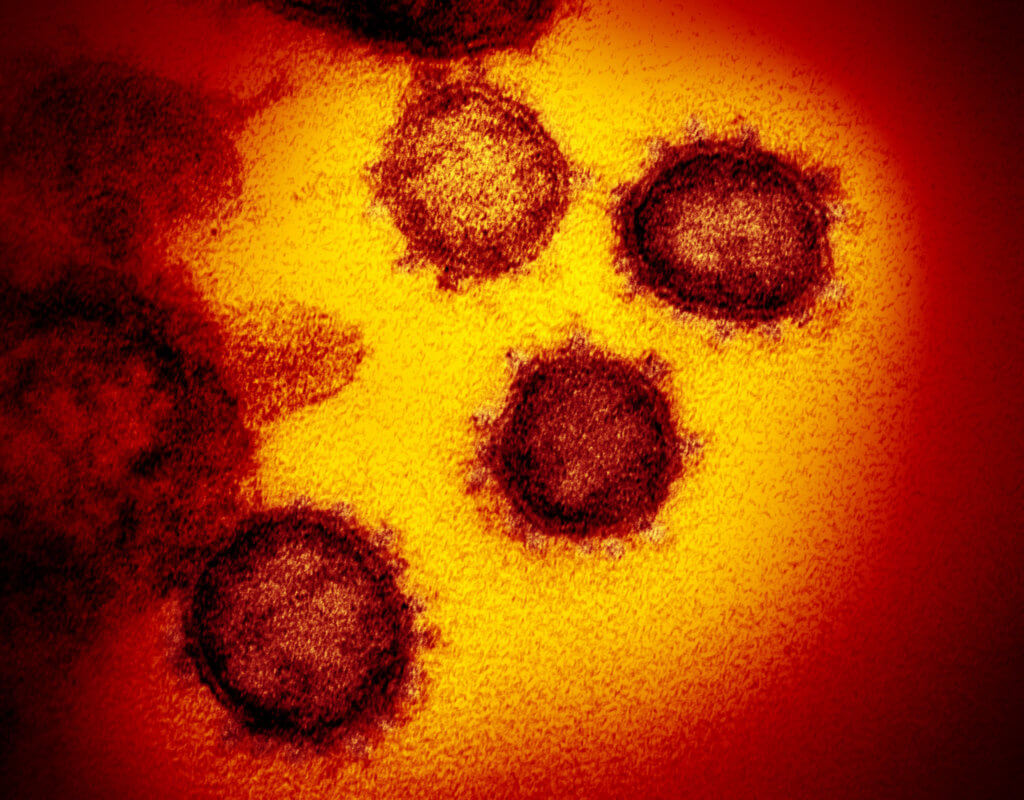

Whether it’s a food or environmental allergy, when a foreign particle is introduced to the body and enters the bloodstream, the immune system produces an army of antibodies called immunoglobulin E (or IgE, for short) to swarm the foreign invaders, setting off a cascade of allergic symptoms that can range from a mild reaction (such as coughing) to a serious, life-threatening reaction (such as anaphylaxis).

“For example, if somebody eats one or two shellfish here and there, the body’s making [IgE] every time that person is exposed to shrimp, but it may not have crossed a certain threshold beyond which the body says, ‘Hey, I don’t like this anymore and I’m going to … release histamine,’” explained Saffana Hassan, M.D., an allergist at Memorial Hermann Greater Heights Hospital. “That person may still be having a sensitivity to that, except they’re not actually symptomatic at that point.”

However, consuming a bowl of gumbo, which is loaded with shellfish ingredients, could trigger an allergic reaction.

“At that point, it’s too much for the immune system to handle,” Hassan added. “When the IgE crosses a certain threshold, the body goes into hyper-function … and there starts your allergy to a food.”

But experts are still scratching their heads as to what exactly causes adult-onset allergies in the first place.

“We don’t have a good understanding of the cause of adult-onset food allergy or why people who have done remarkably well, enjoyed food for many years and then, for some reason, become allergic to it,” said Sanjiv Sur, M.D., director of the section of immunology, allergy and rheumatology at Baylor College of Medicine. “This is actually an unknown mechanism, but it clearly exists.”

For children with food allergies, oral desensitization is a process in which a certain food is slowly reintroduced in small amounts until it no longer causes an allergic reaction. However, the same protocol for pediatric allergies cannot be applied to adults because the mechanism behind the phenomenon is different.

“In adults, the mechanism is different because these are people who were taking in huge quantities of whatever, whether it’s seafood or nuts, they were eating without any problems,” Sur explained. “You cannot really reintroduce because that’s exactly what they were doing before. … All we can do is play it safe and say, ‘Don’t eat this kind of food in the future.’”

When a person suspects a food allergy, the first thing to do is to consult a primary care physician to make sure it is, in fact, an allergy. “Somebody who may be thinking they have food allergies might actually be having other more severe GI problems, which do need to be diagnosed on time, and the patient may need treatment and medications,” Hassan said.

Food allergies are diagnosed by a skin prick test, during which a health care professional places a sample of the suspected food allergen on either the forearm or back of the patient and gently scratches, without breaking the skin or causing bleeding. If a visible reaction is present on the skin, blood is drawn to determine the levels of IgE antibodies the patient’s immune system is producing.

Once a food allergy is diagnosed and confirmed, experts say patients should always carry an EpiPen—to give themselves an injection of epinephrine—and completely avoid the food allergen.

“If they’re highly allergic, not only do they have to avoid that, but family members and friends also have to be educated,” Hassan said, especially “if they are eating that [food] beside that person and then they’re touching that person with their hands or fingers.”

Unfortunately, even with due diligence and taking every precaution, accidental exposure can

still happen.

“For a long time, we didn’t eat out,” Barbuto said. “It was safer to just eat at home. From a quality of life standpoint, we tried eating out at a couple of places, just so that we could feel a little more normal. We only go to a couple of places. We talk to them—talk to the managers, talk to the chefs—to make sure everybody’s aware, but unfortunately, the risk of going out to eat with a food allergy is that something can happen.”

When people experience difficulty breathing from allergic reactions in public, it is important that they not isolate themselves.

“It’s OK to be in distress in front of others because they can help you,” Sur said. “But if you feel that you don’t want to embarrass others and go to the restroom, you close the door and there’s no one else there. That’s the worst possible mistake you can make.”

Can adult-onset food allergies disappear just as quickly as they appeared? Yes, theoretically, Hassan said.

The more you become exposed, the more IgE antibodies your body makes, she said.

“The opposite is also true, that the less you get exposed, the antibody levels drop,” she added. “Now, does it drop to a certain threshold below which you won’t have a reaction? Theoretically, it’s possible, but would I actually want to test out a patient if they have had anaphylaxis? No, I probably wouldn’t.”