Mummies didn’t eat fast food, but their ancient arteries hid high cholesterol

Clogged arteries didn’t originate in the era of fast food after all, according to a new technique used to examine mummies.

A study appearing this month in the American Heart Journal revealed that our ancestors suffered from unhealthy levels of cholesterol similar to modern humans.

“We were wondering if this is a disease of modern age or not. I’ve had that question since medical school,” said Mohammad Madjid, M.D., M.S., the study’s lead author and an assistant professor of cardiovascular medicine with McGovern Medical School at The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth). “We know atherosclerosis starts very early, from the teen years or even earlier. By the age of 18, 20, many people will form plaques in their arteries. We have seen this in our modern-day studies. But then we look at our ancient ancestors and my study found that actually the majority of adults at that time had very similar amounts of cholesterol in their arteries, so it’s not a disease confined to our current day.”

Researchers used a technique called near-infrared spectroscopy to examine arterial tissue from preserved corpses. The samples came from five individuals who lived between 2000 B.C. to approximately 1000 A.D. The three men and two women ranged in age from 18 to 60. Four lived in South America and the fifth resided in the Middle East.

In the past, researchers have used computerized tomography (CT) scans to study the hearts and arteries of ancient remains, but this is the first time a team has employed near-infrared spectroscopy to examine mummies. Madjid, who is also affiliated with UT Physicians and the Memorial Hermann Heart & Vascular Institute–Texas Medical Center, noted that while CT scans can show calcification of arteries, they cannot detect levels of cholesterol. Near-infrared spectroscopy can. The technique, Madjid explained, employs a catheter to send signals to the mummified tissue which return unique molecular signatures that signify the presence of different components inside the arteries.

“Every component, like water, fat, cholesterol or bone—they each have different molecular signatures, like a fingerprint,” Madjid said. “The technique is widely used in medicine and industry and we know how cholesterol looks. … It is non-destructive and non-damaging to the tissues, which is very important if you want to work with mummies.”

A close-up of a an arterial tissue sample from an ancient mummy.

High cholesterol can lead to plaque buildup in the arteries, which causes atherosclerosis or narrowing of the arteries. When arteries become too narrow, they can block off oxygen and result in a heart attack. The presence of cholesterol-rich plaque is one of the first markers of blocked arteries, which is why detecting levels of cholesterol—rather than relying on the presence of calcification—is so revolutionary when it comes to studying ancient arteries.

“You’ll find calcification in the arteries in some mummies, but calcification is a sign of older-aged plaques,” Madjid said. “Cholesterol-rich plaques can happen very early and we found that there are a number of people who can have it.”

The cardiologist said this finding doesn’t mean people today should ignore a healthy diet and lifestyle thinking atherosclerosis is inevitable, but should place more emphasis on treating and preventing high cholesterol through lifestyle choices and, if necessary, medication.

“I see patients with high cholesterol every day. I see patients with plaques in their arteries every day, and I treat those plaques with medications, ballooning and stenting and angioplasty,” said Madjid. “This study has a good message for us, actually. It looks like, as human beings, we are susceptible to developing these plaques. There is an interplay of genes—and it looks like that goes back to many thousands of years—and there is also a combination of lifestyle. You really want to detect these plaques very early and prevent them from giving you a heart attack.”

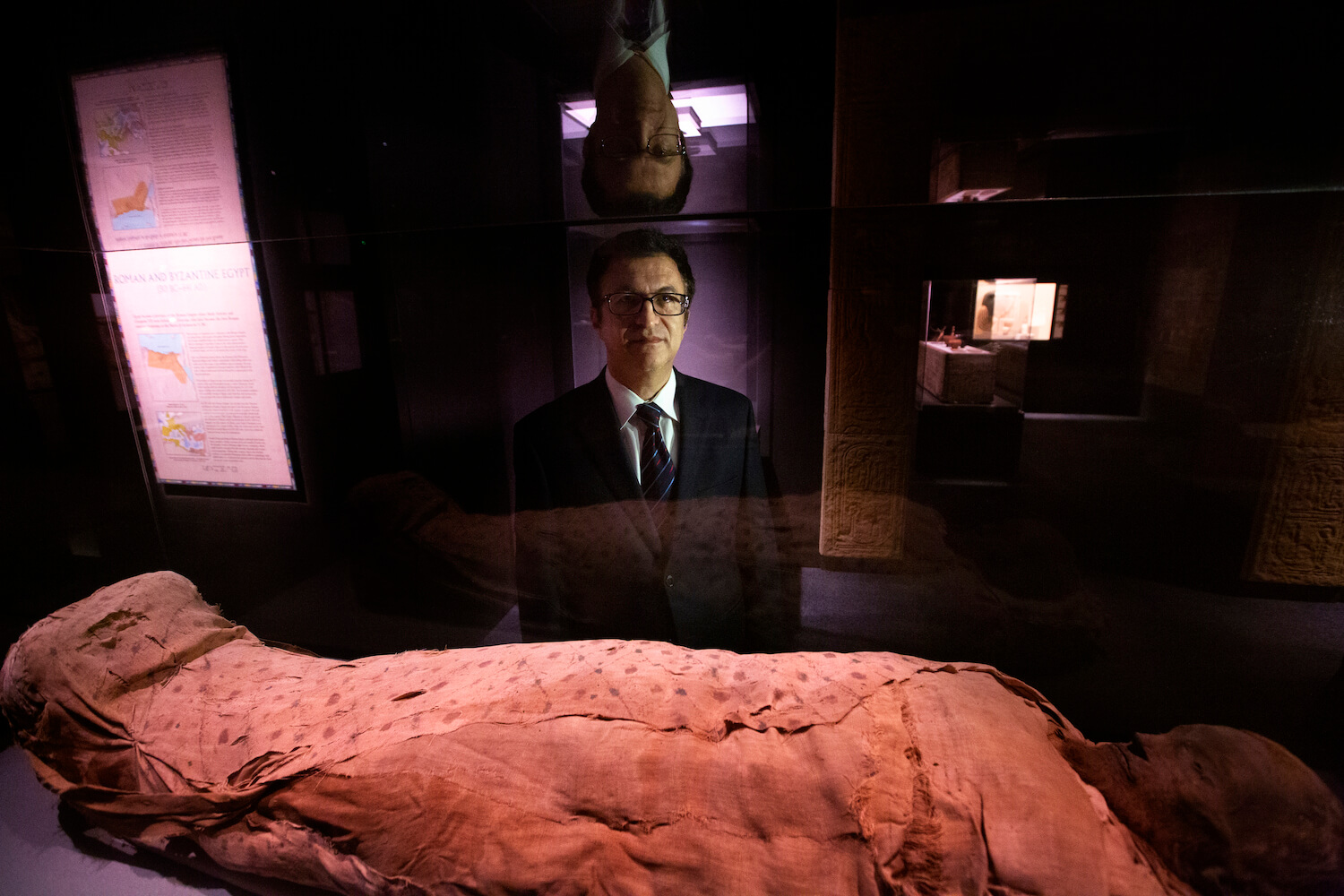

Mohammad Madjid at the Houston Museum of Natural Science’s Hall of Ancient Egypt exhibit with a mummy.

Madjid added that lifestyle factors that contribute to inflammation, like poor diet, smoking, pollution or infection are especially harmful in compounding the effects of atherosclerosis and should be avoided.

“It’s not only cholesterol sitting there which causes a heart attack. It’s cholesterol with inflammation on top of that within the artery wall—that’s the killer,” said Madjid. “Humans are very susceptible to atherosclerosis … but the message is that heart attack is totally preventable. We can detect these plaques, we can prevent them and we can treat them.”

The mummies studied for this research succumbed to infection or disease—not high cholesterol, Madjid noted. Like most ancient humans, they didn’t live long enough to die from atherosclerosis, but the sharp rise in human life expectancy means we can and do.

“Prevention is the key here,” Madjid said, referring to cholesterol build-up.

Moving forward, the cardiologist—who has been fascinated by ancient cultures since primary school—hopes to expand his research to more mummies from other parts of the world to see if cholesterol levels vary by geographical region and time period.