‘Best intentions’ won’t solve implicit bias in health care

When you encounter a new person and start to write a story in your mind about them based on nothing more than your own experiences, that is called implicit or unconscious bias. Implicit bias encompasses attitudes and assumptions about race and ethnicity, but also gender, weight, age, social stratum and other classifications.

In some ways, making snap judgments is how we order our world—slotting people quickly into our own predetermined categories.

But in medicine, implicit bias creates blind spots that can have real consequences for health outcomes.

Physical therapy students, for example, who tend to be young, athletic and fit, have confessed to biases against heavier patients or those with sedentary lifestyles, said Jeffrey S. Farroni, Ph.D., J.D., an associate professor of clinical ethics with the Institute for the Medical Humanities at The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston (UTMB). After learning about their unconscious attitudes, those same students aimed to transcend those thoughts to ensure that they provided all of their patients the same level of care.

“It’s compassionate honesty that puts us in a position to do our jobs better and take care of folks,” Farroni said. “How can we get better if we don’t challenge ourselves?”

For the past two decades, the implicit association test, or IAT, has helped people recognize their personal biases. Created in 1995 and first published in scientific literature in 1998, the IAT has become the foundation for equity, diversity and inclusion training across institutions in the Texas Medical Center and beyond. The test helps to educate medical students, edify employees and hire leaders.

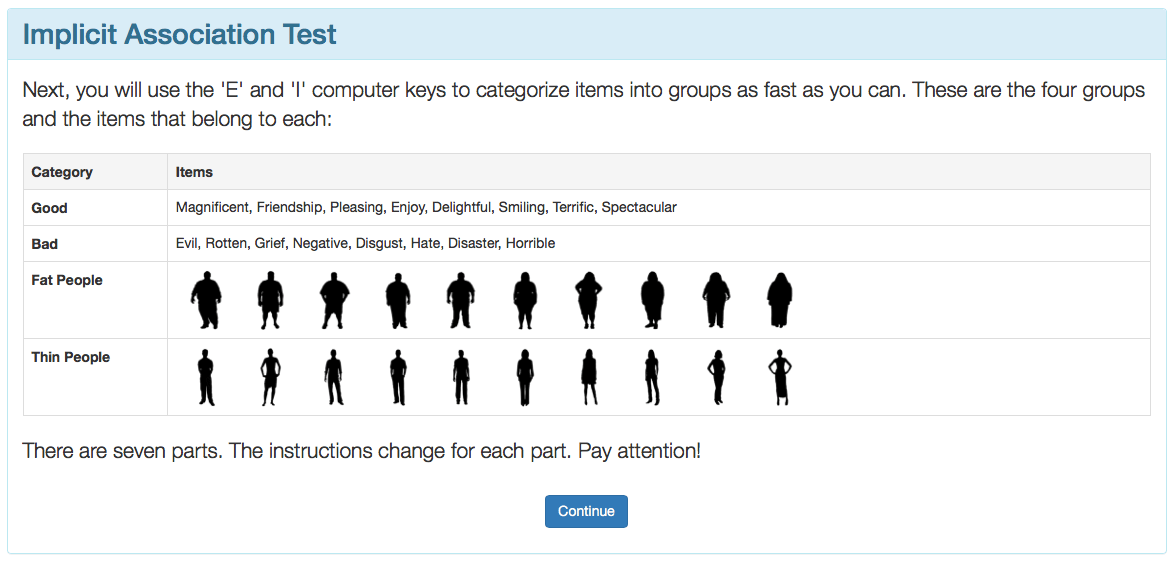

The IAT quizzes different associations between photos, other images and words to determine whether someone has slight, moderate, strong or no preferences. For instance, to measure leanings toward Republicans or Democrats, quick-fire images of Ronald Reagan, Barack Obama, an elephant or a donkey appear. If you are faster responding to associations that pair “good” and “Republican” than associations that pair “good” and “Democrat,” then you likely have some preference for Republicans over Democrats.

An opening screenshot of an IAT measuring bias related to fat and thin people. The following screens show sections of the test asssociating thin people with bad words and good words with fat people, then the switching good to match thin people and bad to correlate with fat people.

Baylor College of Medicine professor Anne Gill, DrPH, started working with bias after reading a 2007 medical journal article about how blood clot treatment for black and white patients could be predicted by the results of physicians’ IATs. The groundbreaking study was the first to analyze whether unconscious racial bias predicted the clinical decisions of doctors.

“It was a very moving and compelling article that really began to show that our unconscious bias or our implicit biases do impact the way care is rendered,” Gill said. “What was remarkable in this particular article was that the physicians that were included in the study were residents and so they were much younger and much more progressive and really felt that they did not have any biases.”

The best intentions

One phrase in the article captured Gill’s attention: “Implicit biases may affect the behavior even of those individuals who have nothing but the best intentions.”

The best intentions.

Around the same time, Baylor received a National Institutes of Health grant to increase behavioral and social sciences training in medical education. Gill used the funding to develop a workshop to determine whether or not the course was a useful strategy to identify bias.

It was. And not long after, Baylor added the unconscious bias workshop—taught by Gill until recently—to its third-year medical school curriculum.

“When we first began, it was so new and novel,” Gill said. “Now, the students seem to be much more accepting of the process and more willing to admit that they have biases and they are concerned. They want to know how to deal with them.”

But initiating conversations about sensitive topics isn’t easy.

“The challenge from an educational point of view is how you make these topics resonate for people,” Farroni said. “The great example is white privilege. I’ll bring that up in some sessions and you see white students’ eyes bulge out like: What are you talking about? or like it doesn’t apply to them. When you open up that space, it’s tricky. These tend to be very delicate topics that we tend to not talk about, which is why we need to. If you can create a space where students can explore these things and look into themselves, it’s pretty amazing how it opens their eyes.”

Students at McGovern Medical School sit for mandatory unconscious bias lectures and “are encouraged to take the IAT,” said LaTanya J. Love, M.D., vice president for diversity and leadership development at The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth), which includes schools of nursing, dentistry and public health. She also serves as associate dean for admissions and student affairs, associate dean for diversity and inclusion and associate professor of pediatrics at the medical school.

“We’re trying to bring a lot more awareness to what unconscious bias is and how it can affect health care delivery, how there can be unconscious bias against a health care provider and—once we recognize our own biases as health care providers—ways that we can overcome them,” she said. “It’s our responsibility to bring awareness in this diverse city.”

In her role at UTHealth, Love has helped develop unconscious bias training for members of search committees, which are usually formed to fill leadership positions, such as dean, department chair or division director, “so we don’t potentially overlook a wonderful leader,” she said.

UTHealth also has worked with its partner, Memorial Hermann Health System, to address bias against health care workers.

“For instance, a patient says I don’t want a doctor of a particular ethnicity, religion or gender. How do we handle that?” Love said. “We formed a committee to come up with policies about handling these types of situations.”

Unconscious bias classes have been offered for the last eight years at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, but are now a mandatory part of annual training, said Larry Perkins, Ph.D., associate vice president of talent and diversity. Weekly courses are offered for the center’s 21,000 employees and 3,000 leaders.

The commitment stems from Houston’s status as a majority-minority city.

“Over 50 percent of our employees come from an underrepresented group. Our patient population is diverse. We have a global patient population. On any given day, 54 different languages can be heard in this institution,” Perkins said. “Awareness is our priority. In our new employee orientation, we talk about diversity and inclusion.”

In an era of mass shootings that sometimes target specific racial, religious and ethnic groups, medical personnel serve on the front lines, delivering trauma care to victims in emergency departments, psychiatric support to survivors and comfort to the families of the deceased. In such a high-stakes environment, medical workers who are trained to confront and push against their own biases have taken a significant step toward healing a troubled nation.

The implicit revolution

The “implicit revolution” is still evolving, said Janice Sabin, Ph.D., research associate professor at the University of Washington School of Medicine who works with IAT co-creator Tony Greenwald, Ph.D.

“It’s a whole new way to understand why extremely well-meaning people can potentially behave in a biased way. In health care, people are altruistic and very well intentioned, so why are there still disparities in care?” she asked. Then she answered: “Bias in medical decision-making has been studied for 30 years. It’s basically how our minds work. We make snap judgments. We assess things quickly so that we actually function in our world.”

Sabin, who also is affiliated faculty of the University of Washington medical school’s Center for Health Equity, Diversity and Inclusion, commends organizations that use the IAT, bias training and ongoing discussions, but cautions that the test itself should remain voluntary.

“We never force anyone as homework or as part of a program to take an IAT because to go into that cold and not know what that really means can be damaging,” she said. “Giving people context on what an IAT result means is super important. You can come away demoralized or defensive. … Understanding what it means—that you make associations really quickly and that this could impact patient care—that’s the crux of what people need to know.”

Baylor, UTHealth and UTMB are among the TMC institutions that spread awareness of unconscious bias to admissions, faculty hiring and health care delivery.

“One of the key things about implicit biases is that people generally don’t know that they have them,” said social psychologist Kate Ratliff, Ph.D., an associate professor of psychology at the University of Florida. “We have these associations that can influence our judgment and the way we behave, but people typically aren’t very aware of them. The IAT and measures like the IAT allow us to assess them.”

Ratliff is the executive director of Project Implicit, an international collaboration of researchers including IAT co-creator Greenwald who are interested in implicit social cognition. The nonprofit advises universities, medical schools, corporations and other organizations about ways to reduce bias.

The test is not designed as a diagnostic tool, but as an educational first step that “can be really eye-opening for people who generally think that they’re unbiased,” Ratliff said.

Test results can bring people to new realizations about themselves.

“After that, the question is developing practices that help prevent those biases from influencing behavior,” Ratliff said. “You have to actively work to figure out how you’re going to stop those biases from influencing how you actually treat patients.”

‘Off Label’

That’s been the goal of a constellation of efforts at UTMB, where bias training has challenged health care provider assumptions about patient immigration status or disposition.

Farroni cites the frustration of physicians who complain about “non-compliant” patients—those who don’t follow the prescribed treatment regimen.

“Maybe what’s happening medically right now is not the most important thing in their life and it’s just not a priority based on these other things,” he said, reflecting on how he counsels doctors. “Now, to a medical person, they say: What do you mean? But, people have complicated lives.”

Another arena of reckoning at UTMB is an employee gathering called “Off Label,” where participants meet without wearing their identification badges.

“We get rid of hierarchies and there’s no agenda—it’s just whatever is on your mind. The only rules are to be respectful and attentive,” Farroni said. “The experience has been awesome.”

In one instance, some nurses were upset about the gravely ill patients selected for care on a floor.

“In that session, there was a senior faculty physician who got to listen to the experiences of the nurses who were faced with the consequences of decisions he was making as a physician. He had never gotten to hear that before,” Farroni said. “He never had to be with the patients for long periods of time. What he also got to do was to provide an explanation about the decisions he made and the nurses understood. They were able to break down communication barriers and they all came away with new understanding.”