In the age of vaccine skepticism, doctors are developing a new skill: the power of persuasion

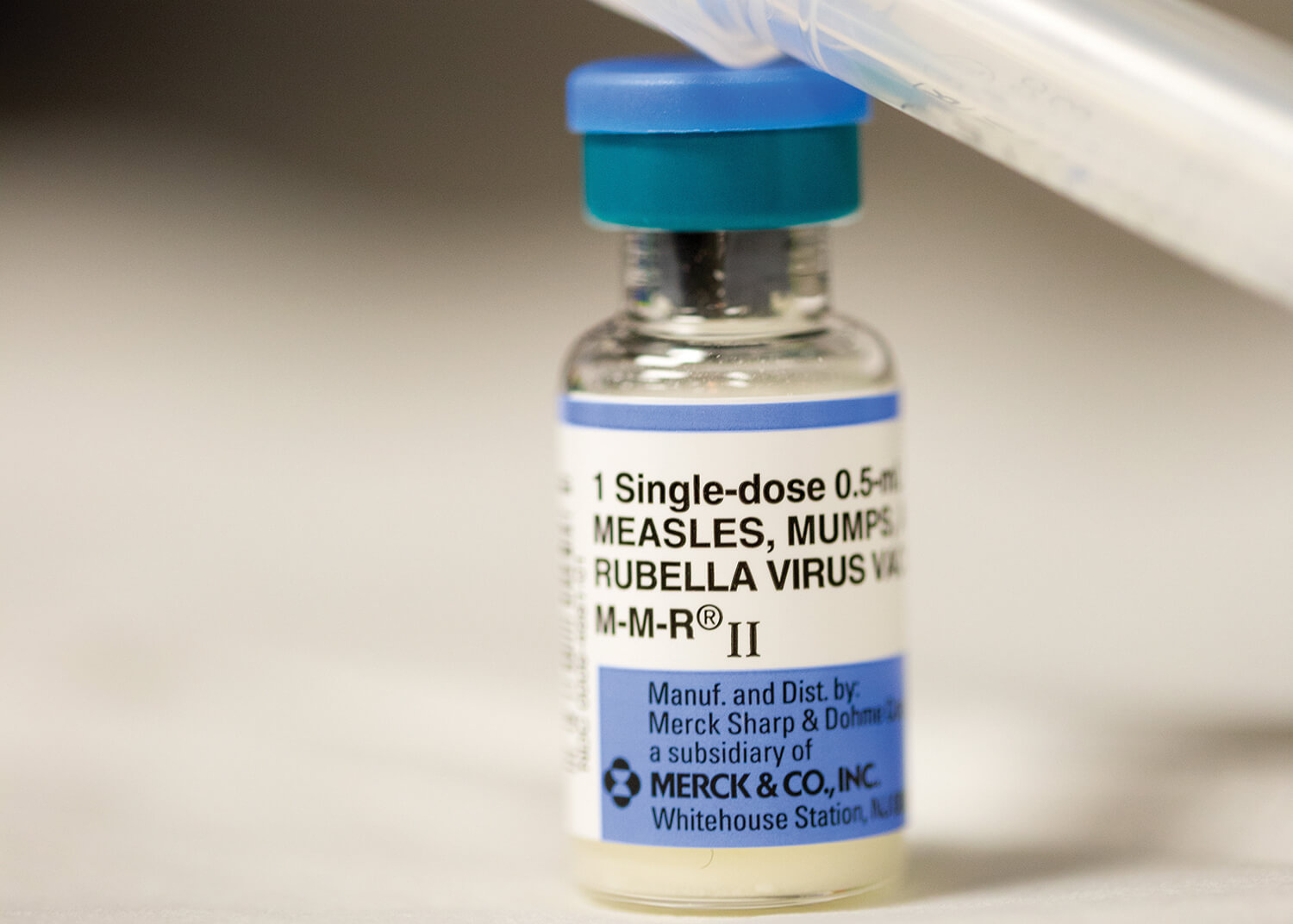

Nineteen years ago, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) declared that measles—a highly contagious and potentially deadly disease—had been eradicated from the United States thanks to an effective vaccine, a robust vaccination

program and a strong public health system.

Fast forward to August 2019, and more than 1,200 cases of measles have been confirmed in 30 states in 2019 alone. According to the CDC, this is the greatest number of cases reported in the U.S. since 1992.

What happened?

An increasing number of parents began declining vaccinations. Known as anti-vaxxers, vaccine-hesitant, and vaccine choice activists, the group gained momentum after Andrew Wakefield, a British doctor who has since been stripped of his medical license, published now widely disproven research linking certain vaccines to autism spectrum disorders.

The medical community is fighting back.

To quell the fears of hesitant parents and deliver the truth about vaccines, more physicians and other medical professionals have started employing methods used by pediatricians to communicate with parents and address their most immediate concerns.

“There’s a lot to learn about these conversations and what conversations work,” said Susan Wootton, M.D., infectious disease specialist and associate professor of pediatrics at McGovern Medical School at The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

It is important to focus on a specific concern, she said, and then help parents understand the information around that concern.

“It’s not a conversation that will necessarily turn the parent around immediately—it might take several visits to talk about it and hear what it is they have questions about, but I think it’s essential to maintain that relationship and help them find their way. It’s really about being an ally,” Wootton said, emphasizing the importance of patients having a medical home where there is a trusting relationship between the patient and the provider.

It is also necessary to address any vaccine myths head-on by debunking them first, then labeling them, stating why they are not true, and finally replacing the myth with accurate information, she added.

“You want to provide them with the truth that fills in that biggest concern,” Wootton said.

Finally, she cited a shift in language termed the “presumptive approach.”

“This is when a doctor comes in and says, ‘Today we’re going to do your flu shot,’ rather than coming in and saying, ‘Do you want to have your flu shot?’” Wootton explained. “A presumptive framing is more effective than the ask, and that’s a simple thing to train providers on.”

In August, STAT News published a story about an initiative in Québec that stationed a new workforce of vaccine counselors in maternity wards. Their goal was to employ a “no-pressure strategy,” using a technique called motivational interviewing to speak to parents about their opinions about vaccinations and then offer to answer any questions or concerns they may have.

Other methods are in the works. At the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases, Saad B. Omer, MBBS, Ph.D., director of the Yale Institute for Global Health, encouraged pediatricians to frame the conversation in a way that focuses on the disease and its potential consequences rather than the safety of vaccines, according to a June article published in Pediatric News.

But one of the issues at hand is not simply how the conversations are being framed, but if a meaningful conversation can take place at all.

“Most parents aren’t deeply dug in—they’re just scared and inundated with misinformation, and it requires a conversation, and sometimes that can go on for 20, 30 minutes,” said Peter Hotez, M.D., Ph.D., dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine and director of the Texas Children’s Hospital Center for Vaccine Development at Baylor College of Medicine. “The problem you get into is the logistics of having a 30-minute conversation in a busy pediatric practice.”

It makes sense, then, that the initiative in Québec included a new classification of employees— rather than tacking on a time-consuming yet critical task to the caseloads of already-busy pediatricians and nurses.

Agreement and divergence

The anti-vaccination movement continues to rise, in part because its members are vocal, social-media savvy and appeal to some of the most basic of human desires: that of a freedom to choose and a longing to keep loved ones safe.

And therein lies the crux of the issue: While the medical community has proven time and again that vaccines are safe and effective in preventing a multitude of diseases, many vaccine-hesitant parents still conclude that the safest choice for their children is letting nature take its course.

“The one thing we can all agree on is that we want our children, and we want our families, to be safe and healthy,” said Rekha Lakshmanan, MHA, director of advocacy and public policy at The Immunization Partnership, a Houston-based nonprofit that promotes vaccination through education initiatives, policy efforts and community outreach initiatives. “Where there is some divergence, however, is where and how you get the information, and what information you use to make that informed decision.”

According to experts, parents are increasingly turning to the internet as their voice of authority on the topic.

“There is a lot of misinformation, and I think it’s really hard to navigate what’s out there—we call it ‘Dr. Google,’” Wootton said.

Hotez noted that the latest data suggests there are at least 480 anti-vaccine websites, many of which are widely circulated throughout social media.

“You’re more likely to download misinformation than you are real information,” Hotez said. “Most of the time, parents are willing to have their kids vaccinated; it’s a very small percentage of parents who are deeply dug in. It’s just that they’re scared because they download all the misinformation, which is ubiquitous on the internet.”

Lakshmanan echoed Hotez’s assertion that the anti-vaccination movement is small but powerful.

“At the end of the day, people who are opposed to vaccines are a relatively small group of people, but they are extremely vocal and engaged in advocacy, and as a result of their loudness, they look and feel a lot bigger than what they really are,” Lakshmanan said, adding that The Immunization Partnership urges parents to listen to their physicians rather than what they’ve read online.

“Although physicians educate their patients, they also need to advocate for strong, sound immunization policies and educate policy makers,” she added. “Physicians are not only a trusted voice to patients, they are a trusted voice to policy decision makers.”

At the moment, the number of unvaccinated children in Texas is rising.

“We’ve got over 64,000 kids not getting vaccinated, and these are the ones we know about—we don’t know anything about the home-schooled kids,” Hotez said. “This issue is not going to go away any time soon.”