Bioengineered lungs: How long from pigs to people?

In 2001, pediatric anesthesiologist Joaquin Cortiella, M.D., arrived at The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston for a job interview. Over lunch at the Galveston Yacht Club, he fell deep into conversation with Joan Nichols, Ph.D., a UTMB professor of internal medicine, microbiology and immunology.

As Cortiella and Nichols grew more and more impassioned about possible research opportunities, they started to scribble down ideas on a used napkin and came up with a bold plan: to create viable organs in the lab. In between the food stains, they sketched out a diagram for potentially infusing a combination of stem cells from Nichols’ lab with lung-derived cells on a scaffold—a DNA-free, blank-slate structure—and, subsequently, transplanting the lung into an animal.

“When we first wrote this out, it was like science fiction,” said Cortiella, who directs the tissue engineering and organ regeneration lab at UTMB. “A lot of things there didn’t happen until much later. We really thought outside the box at that time. … It’s still kind of science fiction-y now.”

More than a decade after their first meeting, Cortiella and Nichols took one large step toward turning science fiction into reality by creating and subsequently transplanting four lungs into adult pigs—with no medical complications.

Oreo cookies

Cortiella and Nichols hope to quell the national shortage of donor organs with bioengineered organs.

More than 113,000 patients are listed on the national transplant waiting list, according to U.S. Government Information on Organ Donation and Transplantation. Unfortunately, the organ shortage in the country continues to grow, as the number of patients in need exceeds the number of donors. Another person is added to the waiting list every 10 minutes, while 20 people die each day waiting for a lifesaving organ transplant.

Yet a large number of less-than- perfect donated organs are discarded because they don’t meet the strict federal criteria for transplantation. In 2016, nearly 5,000 donated organs were thrown out—including 221 lungs—because they were deemed “unsuitable” for transplantation due to “disease, injury to the organ, and the lapse of too much time between recovery and transplantation,” according to a 2017 report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

“There are more lungs that are being thrown away than there are being transplanted, so there are a lot more people also waiting on a list to be transplanted. Unfortunately, the majority of them don’t get it,” Nichols said. “This was a way to look and see if we could take a lung that they’re going to throw away or put somewhere, isolate the cells, take the scaffold and then start again.”

Throughout the entire study, the pigs were trained exclusively with Oreo cookies, which allowed the researchers to perform tests and checkups without the pigs squirming. The team’s veterinarian wrote an actual prescription with strict instructions to feed the pigs with Oreos for “pre- and post-transplant enrichment,” according to Nichols.

In total, the researchers harvested and transplanted four lungs. As the lungs stewed in the bioreactor for a month, Nichols treated each of the pigs and each lung like a patient awaiting a transplant.

“I’d come in in the middle of the night and check on them,” Nichols said. “We’ve got a lung for a pig, and the pig is waiting to receive the lung, so we’d better have a lung to give them. … They were all important to us. They were our transplant patients, and they gave us everything to do this research. We couldn’t have done it without their involvement.”

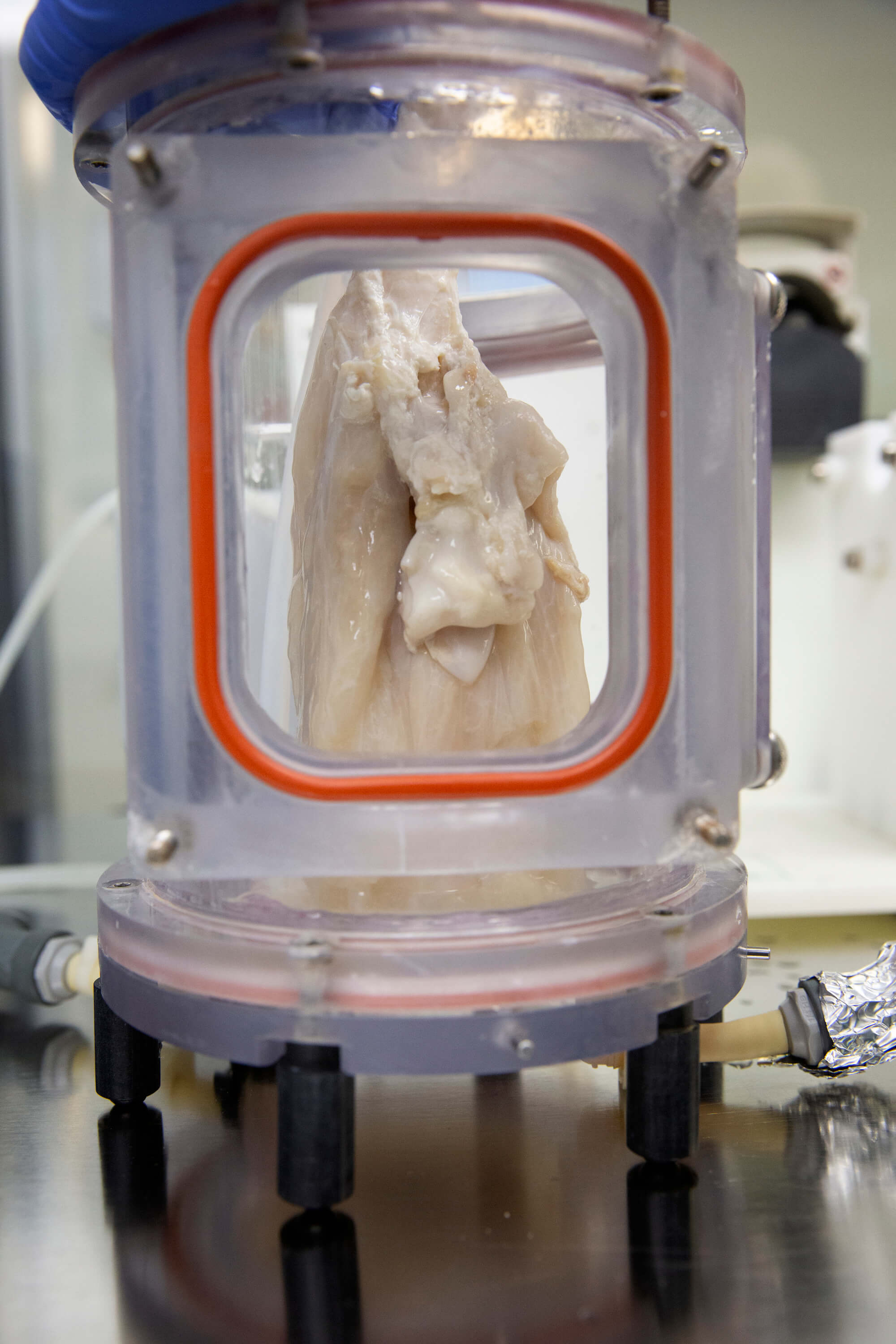

To create the scaffold, the team took a single lung from another pig and stripped the cells—a process called decellularization—using a detergent and sugar solution. The detergent removes all traces of blood and cells, while the sugar protects the collagen and elastin proteins from deteriorating. What is left is an off-white, gauze-like ghost of a lung. Washed clean of all traces of DNA, the lung scaffold is translucent, with only its branching arteries visible.

The scaffold is then hooked up to tubes and placed in a bioreactor, where it is infused with nanoparticles delivering a special concoction of growth factors—including platelet-rich plasma, fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2) and keratinocyte growth factor (KGF)—for 30 days. (The team handmade their first bioreactor in 2013 from a Petco fish tank and nuts and bolts from the local Home Depot hardware store.)

A bioengineered lung hangs in a bioreactor, where it is infused with nanoparticles delivering a special concoction of growth factors.

The team also reconstituted an immune system in the new bioengineered lungs by replenishing it, pre-transplant, with alveolar macrophages— which clear out infectious and toxic particulates that pollute the respiratory tracts—and infusing it with a serum made up of the pig’s blood cells.

“As an immunologist, I understood that if you just put in a sterile lung, you’re going to get an infection,” Nichols said. “Without an immune system in the lung as it developed, we don’t get past 15 days. You get a fungal contamination overgrowth.”

Where other researchers tried to transplant bioengineered organs and failed—because the animals suffered complications—Nichols and Cortiella had four pigs that thrived. The bioengineered lungs developed a fully functioning network of blood vessels and lung tissues without additional infusions of growth factors within two weeks of being transplanted.

All of the pigs remained healthy, but were euthanized post-transplantation after 10 hours, two weeks, one month and two months, respectively, so the team could assess how well the bioengineered lungs adapted to their new host environment.

While the animals’ blood oxygen levels were holding at 100 percent because each pig still had one of its own fully functioning lungs, the bioengineered lungs were not developed enough for the researchers to allow the animals to breathe exclusively with the lab-grown organs.

‘All of these little pieces’

Determining how well animals fare with only bioengineered lungs is the next challenge for Nichols and Cortiella.

As a byproduct of all their work with bioengineered organs, the researchers have made interesting and important discoveries that could impact science in a variety of ways. By learning how to revascularize and rebuild the vascular system, for example, they’ve developed a way to enhance tissue development, which has positive implications for wound healing.

“When you look at it that way, all of these little pieces that we’ve come up with don’t just impact what we’re doing for bioengineering lungs. They could be used to help in wound healing, other surgeries, transplantation and the development of other organs,” Cortiella said.

But the big question looms: When will they be able to develop a lung to transplant into humans?

Even with adequate funding, Nichols said it would take at least five to 10 years before they could produce a lung for compassionate use, a designation by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration that allows patients with immediately life-threatening or serious conditions to access investigational treatment.

“Although we worked as hard as we could and as fast as we could, there will always be people who hear about our work and say, ‘I’m willing to be a guinea pig because I need a lung today.’ That’s really hard,” Nichols said. “I spend weekends and holidays in the lab doing this work. You can never work fast enough … to get it to where it needs to be, but you always have to do it well.”

It’s a commitment Nichols and Cortiella are passing on to the next generation.

“We’ve made big advances within my lifetime. Definitely within my students’ lifetime, they’ll see clinical application,” Cortiella said. “Like a relay race, it’s their turn now.”