Santa Fe Survivor: Inside the race to save Officer John Barnes

On the morning of May 18, 2018, Officer John Barnes arrived at work hungry. It was the Friday of National Police Week, and Santa Fe High School had planned an omelet breakfast for its school resource officers—a gesture of thanks and appreciation for keeping students and faculty safe throughout the year.

Barnes can remember the omelets, that they were supposed to be served that morning. But his memory grows foggy when he tries to recall why he first stepped into the hallway, where a woman approached him to report sounds of gunfire. Just one month earlier, Santa Fe High, located about 36 miles southeast of Houston, had ordered a lock-down after rumors of an active shooter circulated; Barnes assumed that this morning’s report, too, would turn out to be a misunderstanding.

But then the sting of gunpowder hit his nostrils. The smell was unmistakable.

Barnes quickly removed his pistol from his belt as a fire alarm pierced the hallway and a rush of students poured out of the gymnasium. Gun by his side, he pushed through the crowd, craning his neck as he listened for gunshots and scanning every square inch of his sight line for someone with a weapon.

Then, he said, it all went to hell.

“People are getting shot in front of me,” Barnes recalled. “And very quickly, everybody either exits out the door or goes past me.”

Barnes was left standing in the hallway, blood smeared on the ground in front of him and glass shattering behind him. Another Santa Fe Independent School District (ISD) officer, Gary Forward, was close behind. Could there be more than one shooter? One behind and one in front? Never, not once, did Barnes think his confusion would be explained away by the wide spray of small metallic spheres from the shell of a shotgun, a weapon worshiped by hunters for its deference to destruction above precision.

Barnes barked into his radio, then focused his attention down the hallway. Slowly, carefully, and with his gun drawn, he slid his body along the left side of the wall, using it, and the corner, as a shield. He was going to sneak up on the shooter. With his pistol out front, he hugged the corner of the wall and drew himself out.

The assailant—Dimitrios Pagourtzis, at the time a 17-year-old student, is accused of the shooting rampage at the school—was standing there with his father’s shotgun, waiting. The teenager allegedly pulled the trigger as soon as he saw the officer’s right arm.

Only 60 seconds had passed since Barnes first stepped out of his office.

**

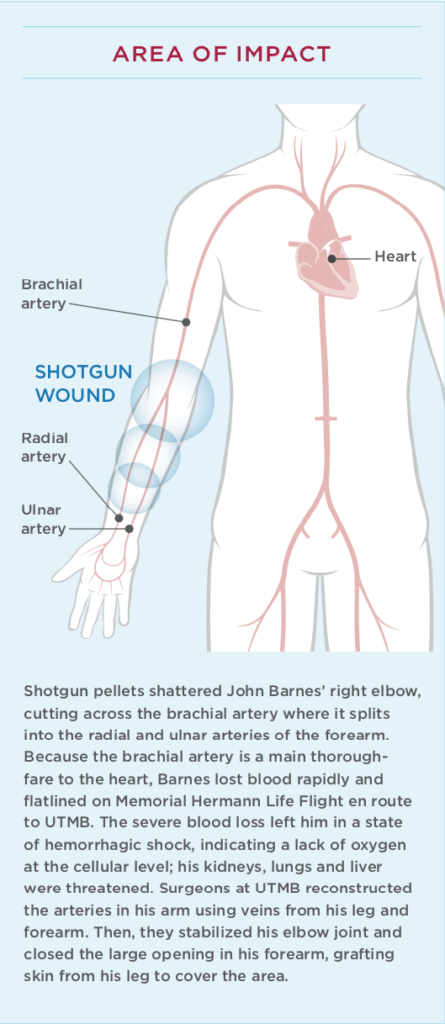

Shotguns are not loaded with the same slick, ogival-nosed bullets found inside handguns or assault rifles. Instead, they use shells packed with tiny metallic projectiles known as shot. Once fired, the shot sprays the target, creating multiple entry points; if a shooter’s aim is off, he or she may still hit a target’s periphery.

Every shotgun shell holds a certain number of pellets. In Barnes’ case, at least three pellets tore through his right arm, shredding his brachial artery, a main thoroughfare to the heart. Barnes, a husband and father of two, would have bled to death within minutes had it not been for Officer Forward, who pulled a tourniquet from his vest and swiftly wrapped it around his friend’s arm. The team had only begun to carry the military-grade devices a month earlier, an addition Barnes had initially dismissed as frivolous.

“It was like somebody stuck a hose in it and it was just draining out,” Barnes would later say of his wound. He can remember looking down at the large hole in his arm and feeling sick.

The two officers kept their eyes fixed on the hallway, waiting for the shooter to swing back around the corner at any second. Barnes kept telling Forward to leave; the thought of a colleague taking a bullet while tending to his arm was unbearable.

But Forward refused, and once the tourniquet was secure, he held open the door to a nearby dance classroom so that Barnes could crawl inside. Then Forward left—

back to the hallway, to the corner and to the shooter. Soon, a group of officers found Barnes and helped him to his feet. He only made it about 10 yards before collapsing to the ground.

“Drag me, just drag me, just drag me,” he remembers pleading. With the threat of the shooter looming, one of the officers, unthinking, grabbed Barnes’ right arm. Pain stunned his whole body.

Ultimately, Barnes was dragged out of Santa Fe High by his duty belt, leaving a trail of blood behind him. Paramedics lifted him onto a stretcher as close friend and fellow Santa Fe ISD officer Elizabeth “Cibby” Moore rushed to his side. They could still hear the roar of gunfire inside the school.

Barnes felt faint, his head somehow both airy and weighted, like he was floating under a lead blanket. His blood was everywhere but inside his body. Amid his haze, he could make out that he was riding in an ambulance. Then, he caught a glimpse of a helicopter. A veteran of the Houston Police Department, Barnes knew Life Flight was his best chance at survival. He turned to the nurse beside him and mustered the strength to speak.

“Get me on that [expletive] helicopter, or I’m going to die,” he said.

***

Word of a school shooting in Santa Fe first made its way to the trauma center at The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston (UTMB Health) when an alert was pulsed out over Emergency Medical Services (EMS) dispatch radio. Abby Anderson, a registered nurse working that morning, said that after one of her coworkers got a call from a student running away from the high school on foot, she and the trauma team began to prepare for victims. This is real, Anderson remembered thinking. This is happening.

Meanwhile, up in the air with helicopter blades whirring above him, an unconscious Barnes had flatlined—his heart stopped beating. The nurses on Memorial Hermann Life Flight pumped two units of blood into his body and he was intubated and fitted with a LUCAS device, a mechanical chest compression system that pulsed his heart with systematic accuracy, automating its beat.

By 8:31 a.m., less than an hour after he had been shot, Barnes was lying in exam room 102 at UTMB. He woke briefly for about 30 seconds, and although he couldn’t open his eyes or even wiggle a finger, he could hear the trauma team calling out orders. He was lulled back into unconsciousness with the assurance that people were trying to save his life.

****

Trauma teams are charged with preserving life and keeping death at bay. Like school resource officers, police and EMS personnel, they are a first line of defense in a medical crisis.

A typical UTMB trauma team is made up of a physician faculty member, three residents and emergency room nurses. The team worked on Barnes for 50 minutes in the emergency room; they inserted a catheter, took an X-ray at the bedside to peer inside his ruptured arm, and packed the wound with QuickClot combat gauze—a fabric impregnated with a clay derivative that clots blood. A nurse initiated a massive transfusion protocol and, shortly thereafter, coolers of blood and plasma and platelets arrived from the local blood bank. They filled Barnes with five units of packed red blood cells, desperately hoping to replenish all that he had lost.

William “Bill” Mileski, M.D., chief of trauma services at UTMB, helped the team stabilize Barnes so that he could be transferred to the operating room for surgery. Described by colleagues as a bear without claws, Mileski can come off as gruff, but if you are in near-irreversible shock from hemorrhaging, you want him in the room.

When a body loses as much blood as Barnes’ did, it pools whatever reserves it has left and drives that blood to the core—one last-ditch effort to survive. But if organs like the kidneys and liver are deprived of blood for too long, their cells begin to die. When the condition hits a critical point, it is called irreversible shock. The patient will enter kidney failure, liver failure, respiratory failure, or all of the above, and it is almost always fatal.

The trauma team at UTMB worked to get Barnes’ blood pressure up to a point where blood and oxygen could still reach his brain—if only barely. At 9:21 a.m., they packed up the coolers of blood, steadied the gurney and rushed him to the OR.

William “Bill” Mileski, M.D., is chief of trauma services at UTMB.

*****

Cibby Moore raced down Interstate 45 toward UTMB in her police cruiser, lights and sirens screaming. Beside her was Barnes’ wife, Ashley, at the time a vice principal at Wollam Elementary School, located just three miles east of Santa Fe High.

Ashley knew her husband had been shot, but nothing else. Finally, Moore turned to her. “Do you want me to tell you what happened?”

Ashley nodded and braced herself. Moore told her that her husband had been shot in the arm. A wave of relief swept over Ashley.

“As soon as I heard that I was like, ‘OK, we got this. We’re in the arm. It’s not in the chest. He’s alive,’” she later recalled.

When the two finally reached UTMB’s waiting room, Ashley took note of the swarm of police officers. How nice, she thought. But when she was escorted from the main area to an isolated room nearby, she grew nervous. Why do I have to be in the ‘Your-husband’s-dead room?’ Ashley took deep breaths. She reminded herself that it was just a gunshot wound to the arm, oblivious to the severity of his injury. Moore remained by her side, her uniform splattered with blood. When Ashley finally noticed, she knew, without question, that the blood belonged to her husband.

Family and friends circled through their small room. Police officers came to pay their respects, even Houston Police Department Chief Art Acevedo. Finally, hours after Ashley had arrived, Mileski appeared.

“He is very sick,” the surgeon told her. “He is very sick.”

******

In the operating room at UTMB that morning, anesthesia was started at 9:23 a.m. The surgeons’ task: determine exactly what damage had been done to Barnes’ body and what needed to be repaired. Everything was recorded in what would ultimately become nearly 900 pages of medical records. A “problem list” outlines the severity of Barnes’ condition:

Gunshot wound

Traumatic hemorrhagic shock

AKI (acute kidney injury)

ATN (acute tubular necrosis—kidney disorder from damage to the tubule cells)

Shock liver

Laceration of right brachial artery

Olecranon fracture

Pellets from the shotgun had shattered Barnes’ right elbow, including the tip, known as the olecranon. The blast transected the brachial artery just where it splits into the radial and ulnar arteries and tore a hole along the front of his forearm. It was no wonder he couldn’t keep blood inside his body.

By 10:20 a.m., the team began to reconstruct the arteries, harvesting fragments of Barnes’ saphenous vein (which runs the length of the leg) and right forearm cephalic veins (large veins often used for drawing blood) for the repair. Three-and-a-half hours later, with a strong pulse in place, the team set to work stabilizing Barnes’ elbow joint using pins and an external fixator. Finally, they closed the large opening in his forearm with the help of wound-VAC, a vacuum-assisted technique that decreases air pressure in and around the wound to promote healing. Last, they grafted skin from his leg to cover the large, delicate area.

The surgeries, finally over just after 4 p.m., required expertise verging on perfection, but Mileski would look back on those first seven and a half hours and say that it was nothing heroic.

“We’re pretty well conditioned to respond to the needs of patients and prioritize what we have to do to get them well,” he said. “You don’t really think that much, as silly as that sounds. It’s like a football player playing football— you react to the circumstance, you don’t sit there and run through a lot of thought, at least not if you’ve been doing it for 30 or 40 years.”

*******

Dimitrios Pagourtzis is accused of killing 10 people in Santa Fe, Texas, and wounding 13, including Barnes.

More than half a century ago, on Aug. 1, 1966, another Texas city ushered in the first mass school shooting in modern America, when a 25-year-old engineering student at The University of Texas at Austin climbed the campus clock tower with an armful of guns and ammunition and shot and killed 15 people.

Since then, the names of the schools around the country where students and faculty have been gunned down are forever fixed in public memory. Columbine. Virginia Tech. Sandy Hook. Marjory Stoneman Douglas. Santa Fe. There are many, many others.

Increasingly, districts are hiring school resource officers to protect students from dangerous situations, including mass shootings. They are usually armed. School resource officers are commissioned, sworn law enforcement officers—not security guards—trained to move directly to any threat, as quickly as possible, and then to neutralize the threat to prevent loss of life or injury, according to The National Association of School Resource Officers.

An estimated 20 percent of all U.S. K-12 schools, public and private, are served by school resource officers.

John Barnes had been a school resource officer for just four months when he rushed toward the sound of gunfire at Santa Fe High. Barnes spent nearly 25 years as a police officer with the Houston Police Department, 10 of those patrolling some of Houston’s toughest neighborhoods and another 13 doing detective work, making a name for himself investigating sex crimes. In January 2018, hoping to slow down a bit and prepare for retirement, Barnes began working at Santa Fe ISD.

Despite more than two decades in law enforcement, May 18, 2018 was the first time Barnes had ever been shot.

Barnes visits exam room 102 at The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, where he was first treated by the trauma team after arriving in the emergency room.

********

When Ashley was finally able to see her husband in the intensive care unit (ICU), his skin was void of color, ashen, “almost all the way through,” she recalled. His body was freezing to the touch.

Barnes came close to losing all the blood in his body, Mileski said.

“It’s difficult to describe the ravages of severe hemorrhage,” the trauma surgeon later explained. “He had lost as much blood as a person can lose and still survive. Honestly, I was surprised he did survive. I didn’t think his kidneys were going to come back, or his lungs, for as sick as he was. But he got lucky.”

Barnes cannot recall anything from his first week in the hospital. In all, he spent nearly three weeks in the ICU, undergoing dialysis to support his kidney function. On June 6, he was discharged and sent to TIRR Memorial Hermann in Houston for inpatient rehabilitation. Then, on Wednesday, June 20, he was finally well enough to go home. Nine days later, he celebrated his 50th birthday.

In August, Barnes made a special trip back to UTMB. He and his wife, with coffees in hand, spent a morning in the ER and at Sealy Hospital, meeting the people who saved his life.

Nurse Abby Anderson, one of the first to treat Barnes on that May morning, spoke up.

“We never get to see this side. We send people that were in your condition to the OR, or up to the ICU, and then we’re done,” Anderson told Barnes. “We may find out from the trauma team later how they’re doing or, you know, what happened, but that’s it. That’s as far as we get. You know, I’ve been doing this for five years, and there’s always patients that stick with you, and you stuck with me for some reason.”

Standing in exam room 102, where crisp white sheets stretched across an empty bed, Barnes grew emotional, thanking those who surrounded him for, in his words, being so good at their jobs. He knew how much that mattered; ballistic analysis would eventually reveal that Barnes’ aggressive march toward the alleged shooter kept the teenager contained, that despite classrooms full of students hiding all around them, Barnes was the last person shot at Santa Fe High that day.

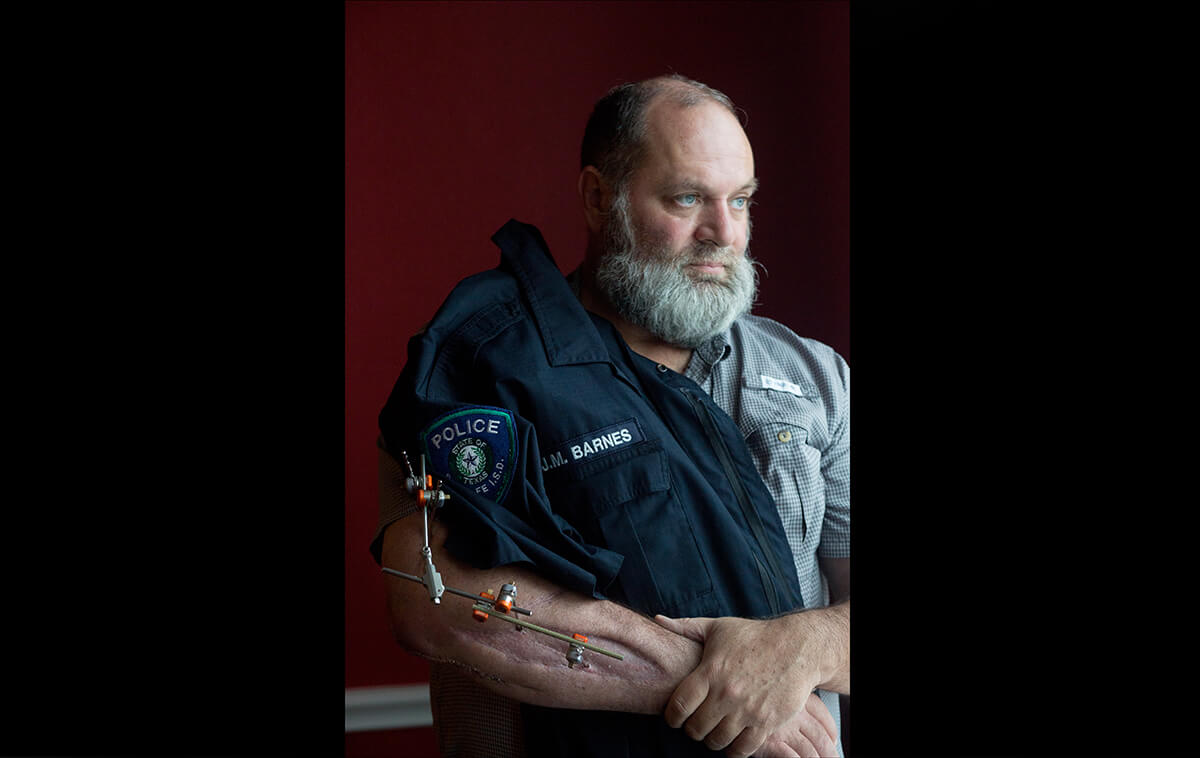

Barnes in August 2018 while visiting with members of the team who cared for him at UTMB.

*********

On a Tuesday morning in early January, John Barnes sat in his home in League City hooked up to an IV drip full of antibiotics. His living room still shone with the relics of Christmas—an unlit tree in the corner, heavy with ornaments, a forgotten Elf on the Shelf, his two children’s wish lists on display. A few months prior, Barnes had awoken with a fever, and then a day later, his arm grew warm. Doctors at UTMB discovered a staph infection and operated quickly, leaving a new scar hugging the length of Barnes’ shattered elbow. It would mark his eighth surgery, with more on the horizon.

Now, every day at 10 a.m., he will hook the IV to a port in his chest until his bones are finally healed enough for surgeons to remove the plate in his arm—a magnet for bacteria. Barnes believes the infection will set his rehabilitation back at least six months, a disappointment in light of how far he’d come re-establishing his range of motion. But aside from his goals of mountain biking again and living without pain, Barnes said life is finally feeling settled. He can take trips with his family. He can enjoy a bourbon and a cigar. He can make plans for the future.

“It’s as normal now as it’s probably ever going to be,” he said. “This is my life now.”

Barnes has been shown the surveillance video from the day of the shooting. He has counted the seconds on the ticker and analyzed every possible scenario, wondering if he could have saved anyone else with the information he’d had that day. He has watched the student with the shotgun wait for him as he turns the corner. It’s surreal, Barnes said—even at the time, he felt like he was inside a movie: His body was responding, his brain was reacting, but he still couldn’t believe it was happening.

He has declined to review all the evidence from the shooting, though. For now, Barnes is focused on healing.

Barnes sits in the dining room of his League City, Texas, home.