Finding Opioid Alternatives

Helen Brindell is not thrilled about taking pain medication.

“I want to manage the pain on my own,” Brindell said. “I like to keep my mind in focus rather than take the drugs and not know what happens.”

To watch Brindell on the job at a landscaping office or to converse with her, it’s hard to tell that behind her bubbly personality and distinct Louisiana accent is a woman who plans her day around the possibility of physical discomfort.

Treatment for a tumor at the top of her spine and fusion surgery on her lower back left Brindell in chronic pain.

In the current health care environment, where providers are increasingly hesitant to prescribe opioids, doctors and startup companies are finding innovative ways to help patients manage chronic pain without relying on high doses of medication.

Among the problem solvers is Rex Marco, M.D., vice chairman of the department of orthopedics and sports medicine as well as chief of reconstructive spine surgery at Houston Methodist Hospital. He said the opioid epidemic started 20 years ago when “pain” became the fifth vital sign monitored by hospitals. Since then, preventing pain with medication has become a standard practice.

As an alternative, Marco now recommends digital health applications, including Stop, Breathe & Think for mindful meditation and The Back Doctor for daily exercises—as a way to avoid taking medication or, at least, to take less.

Brindell tried both apps after going to Marco for her back surgery.

“It’s amazing. The app takes in the information and gives you meditation homework,” she said. “I had 20 minutes of meditation yesterday because my day was not so good.”

Brindell explained that stress exacerbates her pain, but combining meditation and back exercises at night often leaves her feeling better by the next morning.

“Do I feel 100 percent? No, I’m never going to feel 100 percent, but it is enough to get me through the day until I get home and do the meditation and Back Doctor again. It’s like exercising,” she said.

Recently, the meditation techniques got Brindell through a particularly painful medical examination during which a sudden move nearly caused her to jump off the table. Rather than react with anger, she asked for a moment to refocus her mind so she could better tolerate the pain.

Your brain on stress

Being more mindful is not only something Marco recommends to his patients, but a discipline he practices himself.

About three years ago, he started using meditation apps and practicing yoga following some life-changing experiences, including a divorce, one of his children almost dying from a fall and substance abuse problems in the family.

“I didn’t know this about myself, but my brain didn’t ever really stop,” Marco said. “Just sitting there or lying there and being present was a completely new concept to me.”

He has learned that being present is difficult for humans, who are often thinking about the future. While that kind of mental preparation can be helpful in finding success, the same mental acuity can lead people to dwell on what they could have done differently in the past.

“When we think about the future, we are really in a state of anxiety, and when we think about the past, we are often in a state of sadness or depression,” Marco explained. “I was trained to think about how to prevent problems. If you do this, this, this and this, then this horrible thing won’t happen. The people I revered the most were able to avoid problems and complications by having that approach.”

When someone is anxious, the brain tells the body to be stressed out. The amygdala, the part of the brain involved in experiencing emotions, triggers the pituitary gland to signal the adrenal gland to release stress hormones, Marco said.

Even in that situation, people can pretend they are calm even though they are constantly stressed. Marco identified as one of those people, but knew it was not healthy, so he worked to turn his life around.

During his early years of yoga and meditation, Marco found quieting his mind difficult. He would think about things going on in his life, his patients, what just happened moments ago and even what might happen in the next five minutes.

A self-proclaimed perfectionist, he would get upset with himself for allowing his mind to drift. It wasn’t until his instructor said it was acceptable to let his mind drift and come back that he allowed himself to take those steps.

“That was amazing to me,” Marco said. “Probably the first time I tried yoga, I felt a sense of calm.”

It was that sense of calm that inspired him to recommend the same exercises to his patients who were undergoing painful surgeries and wanted to reduce their reliance on opioids.

He read articles that discussed the amygdala as the center of fear and anger and how certain activities could calm those emotions and even help with pain cessation. When Marco sensed fear and anger in his patients, he suggested some of the meditation activities. Not only did patients report back that their anxiety was released, but, like Brindell, they were able to reduce pain, and, in some cases, stop using opioids altogether.

“It’s not going to get rid of all of the pain, but the pain can be lowered through endorphins,” he said. “I’ve seen patients come out of major spinal surgery without narcotics, but just taking regular pain medicine.”

Treating and avoiding addiction

Edythe Harvey, M.D., addiction psychiatrist at The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston (UTMB), treats patients for chronic pain who are addicted to pain medication.

More than 191 million opioid prescriptions were dispensed to American patients in 2017, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality estimates that more than 2 million Americans are dependent on or abuse prescription opioids. And the CDC notes that, on average, 115 Americans die every day from an opioid overdose, which includes prescription opioids, heroin and fentanyl.

Amid an opioid crisis, Harvey and her colleague, pain medicine specialist Courtney Williams, M.D., created a task force to share ideas about educating staff, identifying community resources, monitoring opioid data and examining opioid alternatives.

Harvey confirmed there was a push in hospitals to make sure no one was in pain.

“However, if you are addicted to opioids, what are you going to tell the nurse about your pain? That is a problem,” Harvey explained. “Lots of factors go into prescribing behaviors, which include prescribing more so the pain is taken care of.”

The UTMB Opioid Stewardship team, a result of the task force, is engaged in an awareness campaign. That work includes monitoring resources like the Texas PMP AWARxE system, a prescription monitoring solution to help identify people who may be going to multiple doctors for the same medication, and incorporating that data into electronic health records.

Team members are also exploring prescribing habits and opioid use.

“Most people need a little pain medication to get them through a surgery, but maybe that’s just three days’ worth rather than a 90-day supply,” Harvey said. “We aren’t trying to do a witch hunt—we want people to get their medication— we just recognize it is one of the problems out there.”

Relief at the push of a button

Simply moving can be difficult for people in chronic pain, as can getting a good night’s rest.

Richard Hanbury, who lived with chronic pain for 22 years as the result of a life-threatening car accident which left him in a wheel-chair, now uses his experience to help others.

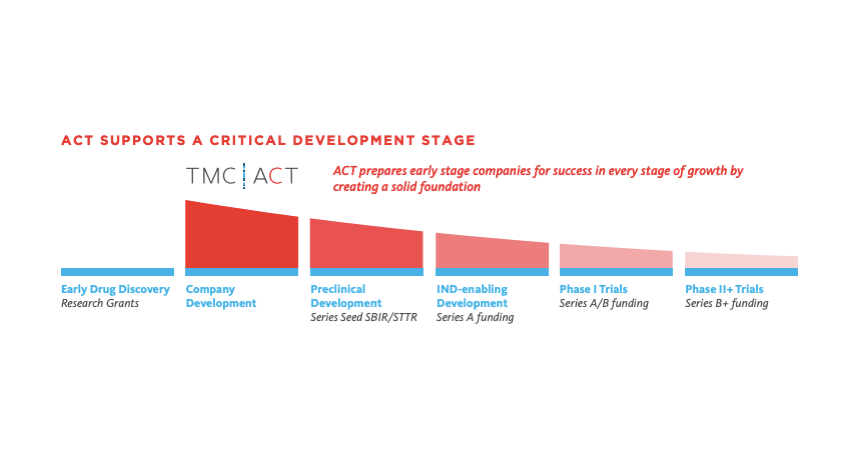

As the founder and CEO of Sana Health, a medical device company attached to the Texas Medical Center’s TMCx accelerator program for health care startups, Hanbury is developing a non-invasive pain relief device that resembles virtual reality goggles. Using neuro-modulated light and sound stimulation, the goggles help patients with severe pain enter a state of deep relaxation in about 10 minutes, which then reduces pain levels.

Hanbury says the device brings the patient to an “altered state of consciousness,” likening the experience to watching a good movie or being engrossed in a sports match. The first day he used the goggles, there was some trial and error, though he still managed to snatch a couple of pain-free minutes. Over time, as the team calibrated the device, Hanbury said those minutes turned into hours and now he is able to enjoy long periods without pain.

“I get normal pain, but I don’t have any nerve damage anymore,” he said, adding that the device was “literally life-saving. It’s given me freedom and more control of my life.”

Sana Health is currently conducting a clinical trial at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York and is moving toward U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval for the goggles. Hanbury will be demonstrating the goggles at the TMCx Demo Day event on Nov. 14 at the TMC Innovation Institute.