A vaccine doctor who’s an autism dad

Rachel Hotez was diagnosed with autism in 1994 at the age of 19 months. As she grew up, her father, Peter Hotez, M.D., Ph.D., a pediatrician-scientist who develops vaccines for neglected tropical diseases, witnessed the rise of an influential anti-vaccine community that persists in connecting vaccines to autism—even though the 1998 paper that first linked autism to the measles, mumps and rubella vaccine was retracted in 2010.

In his new book, Vaccines Did Not Cause Rachel’s Autism, Hotez, dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine and director of the Texas Children’s Hospital Center for Vaccine Development at Baylor College of Medicine, draws on his experience as a physician, academic and father to praise the effectiveness of vaccines and explain what experts are starting to learn about autism.

Q| In your new book, you write quite openly about your daughter, Rachel, and how your family coped with her diagnosis. Your other books aren’t this personal. Why write this book now?

A| I feel an urgency to speak out, driven by something terrible that’s going on in Europe and in many of the western states in the United States, and that is the return of measles. According to the World Health Organization, we had 41,000 measles cases in Europe the first half of 2018 and at least 37 deaths. We’ve got pockets in Texas and other western states where 10, 20, 30 percent of the kids are not being vaccinated, which means we’ll soon have measles return to the U.S. People forget that measles is a killer disease.

Q| Anti-vaccine groups attack you regularly on social media because you have spoken out so stridently against them and written op-eds and journal articles about the dangers of a resurgence of measles. How do you think they will respond to the book?

A| This is going to be a threat to them. They are going to try to exploit any vulnerability they can. One of the things that I anticipate—because they’re pretty nasty, they say I’m making millions of dollars from my hookworm and schistosomiasis vaccines, to which my wife says, ‘If only!’—is they’ll say I’m exploiting Rachel for some kind of personal gain.

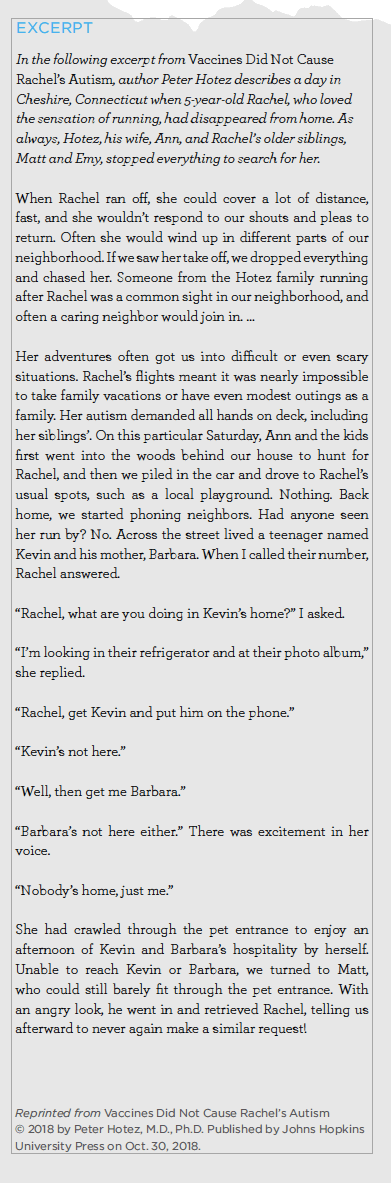

Q| As a little girl, Rachel often ran away. The book shares stories of you, your wife, Ann, and your other children searching the neighborhood for Rachel and alerting neighbors that she was on the loose. That “mostly noncompliant little girl,” as you describe her in the book, is now 26 and still living at home. What’s Rachel like today?

A| She’s still very strong-willed and very determined. She’s got, in some ways, a fuller life than she’s ever had, in part because we’ve given her a lot of freedom to walk in our Montrose neighborhood, where she has befriended various merchants. Everybody knows Rachel. She recruits allies and friends. We’ll go into the Hollywood convenience store and she’ll say, ‘Dad, this is my friend, Vin. He’s from Vietnam. He doesn’t speak English.’ And Vin will say, ‘Hi Rachel.’

Peter Hotez poses with his daughter, Rachel, in their Montrose home. (Credit: Copyright 2017 Brian Goldman/Goldman Pictures)

Q| You observe that Rachel’s autism is atypical but not as atypical as experts once believed. Can you elaborate?

A | This is one of the sub-themes of the book. We used to say autism was 10 to 1 boys to girls, but it’s probably far closer to 1 to 1 than we realize. It’s just different for girls on the autism spectrum. They camouflage it better; they’re more verbal, more interactive, but oftentimes in a very odd way. There are often high rates of comorbidities for girls or women on the spectrum, such asa high incidence of obsessive-compulsive disorder or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. We’re now realizing a lot of adolescent girls with eating disorders are actually on the autism spectrum. It’s the comorbidity that gets diagnosed, not the autism. That’s the big revelation in the book.

Q | In the book, you confess that it wasn’t the autism diagnosis that was so devastating to you and your wife. It was Rachel’s low IQ: “ … we came to an understanding that Rachel would have a very different life from what we had hoped for her. We faced a real possibility that she would not find a life partner, attend college, or have a meaningful career. There was a lot of sadness and sense of loss.”

A | If it was just her autism, per se, that’s not what’s so disabling. There are many men and women on the autism spectrum doing important things. It’s the associated disabilities, the comorbidities, that are so difficult. It’s hard to test her because she’s so impatient. Oftentimes, her verbal IQ is pretty good, but it’s the performance IQ that’s just dismally low. She won’t count money, for example. She can’t do that.

Q| What can you say about the genetic basis for autism? The expectation is that there will be 1,000 or so genes in the total sequencing. Where are we right now?

A | We’ve identified at least 65 genes and that’s just the beginning. One of the things that happened as I was finishing up the book is we did whole exome sequencing of Rachel here at Baylor College of Medicine in the department of genetics and we think we’ve identified a new gene for autism. The question is: What do you do with that information? Can you design interventions to improve especially the comorbidities associated with autism?

Q | These sound like questions for ethicists.

A | We’re already seeing, especially on social media, a lot of interesting questions about genetics from the community of people with autism. They’re saying, ‘What are you going to do with that information? Does that mean you’re going to weed us out? Is this a form of eugenics?’ So we’re really going to need an unprecedented dialogue between autism scientists, psychiatrists, neurologists and bioethicists and people from the autism community.

Q | What are the clinical markers of autism and how early do children receive this diagnosis?

A | The clinical expression of autism is at its most florid often around 18 to 24 months of age. That’s the time when, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a lot of children on the autism spectrum get diagnosed. That clinical expression of autism coincides with when you see a big increase in brain volume expansion on an MRI. We have a good MRI marker of autism through that brain volume expansion, and that’s important because that’s around the same time parents often remember their kid got vaccinated. Now, a research group at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill can go back a full year before and actually show changes on an MRI at six months of age that will predict which children are going to go on to develop those big changes at 18 months. And now a group at the University of California, San Diego can show that the changes are beginning prenatally. So we have a very good theory that there are genetic and epigenetic changes that are beginning prenatally that set into motion a developmental progression. The problem is, that’s not a soundbite.

Q | Rachel is now working at Goodwill. How is that going?

A | Goodwill really came to the rescue for us in a big way. The philosophy of Goodwill is: It doesn’t matter who you are, we’re going to make it work. It’s a very nurturing place. Rachel walks to work and spends two hours a day there, Tuesday through Friday, sorting clothes. You can’t underestimate the power of someone getting their first paycheck. In terms of affirming Rachel’s existence, the satisfaction she gets is huge. The pride she has in that job—you can’t put a price tag on that.

Q | Back to vaccines and measles. Anything you’d like to say to parents trying to decide whether or not to vaccinate their kids?

A | As recently as the 1990s, measles was the single leading killer of children in the world and we’ve allowed it to come back because we’ve allowed an anti-vaccine movement to go unopposed. Vaccines Did Not Cause Rachel’s Autism was very much driven by living in Texas and seeing what’s going on down here with large numbers of kids not being vaccinated—with seeing what an anti-vaccine movement looks like unfiltered, unopposed. Somebody’s got to speak out.

This conversation was edited for clarity and length.