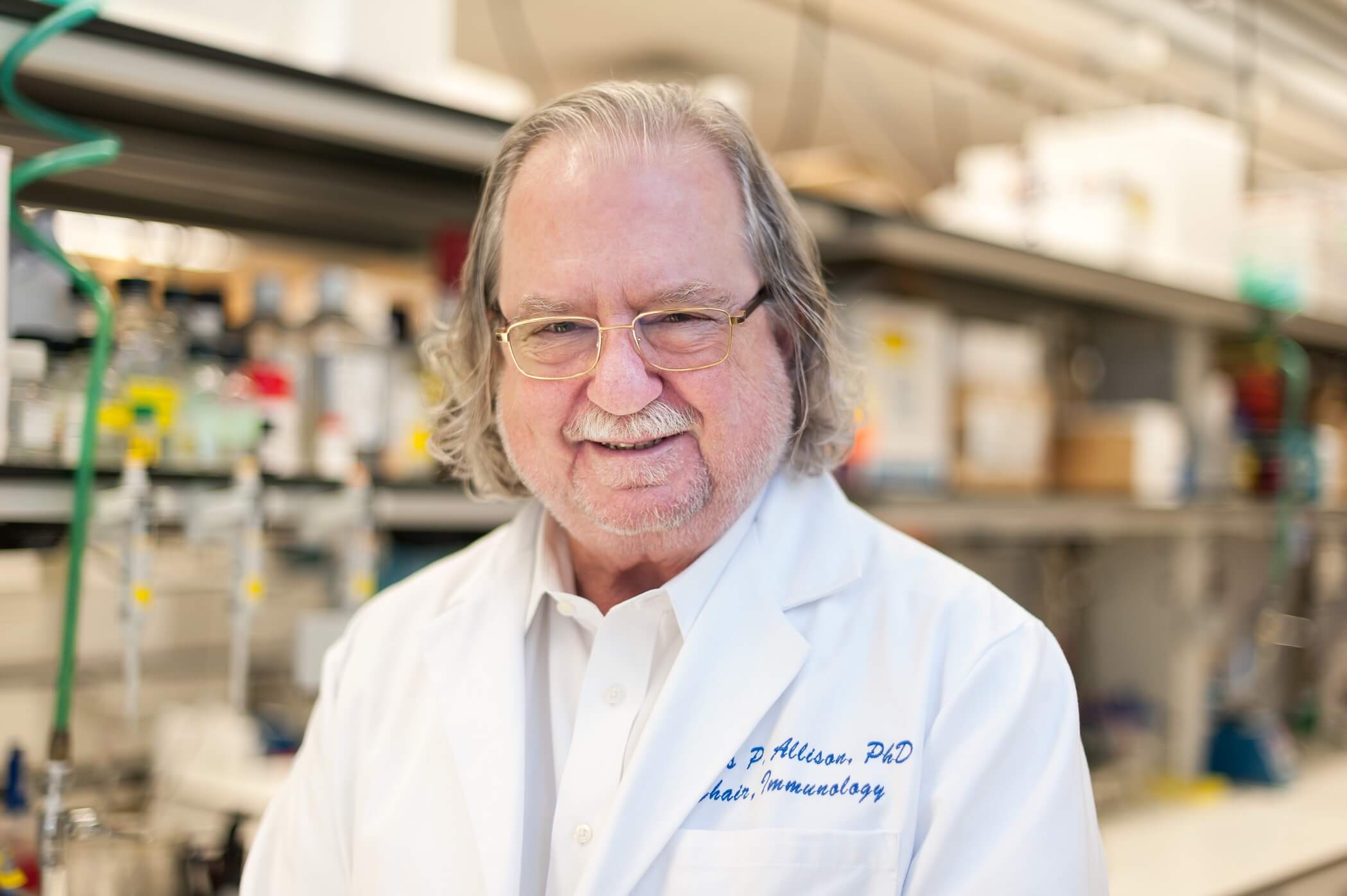

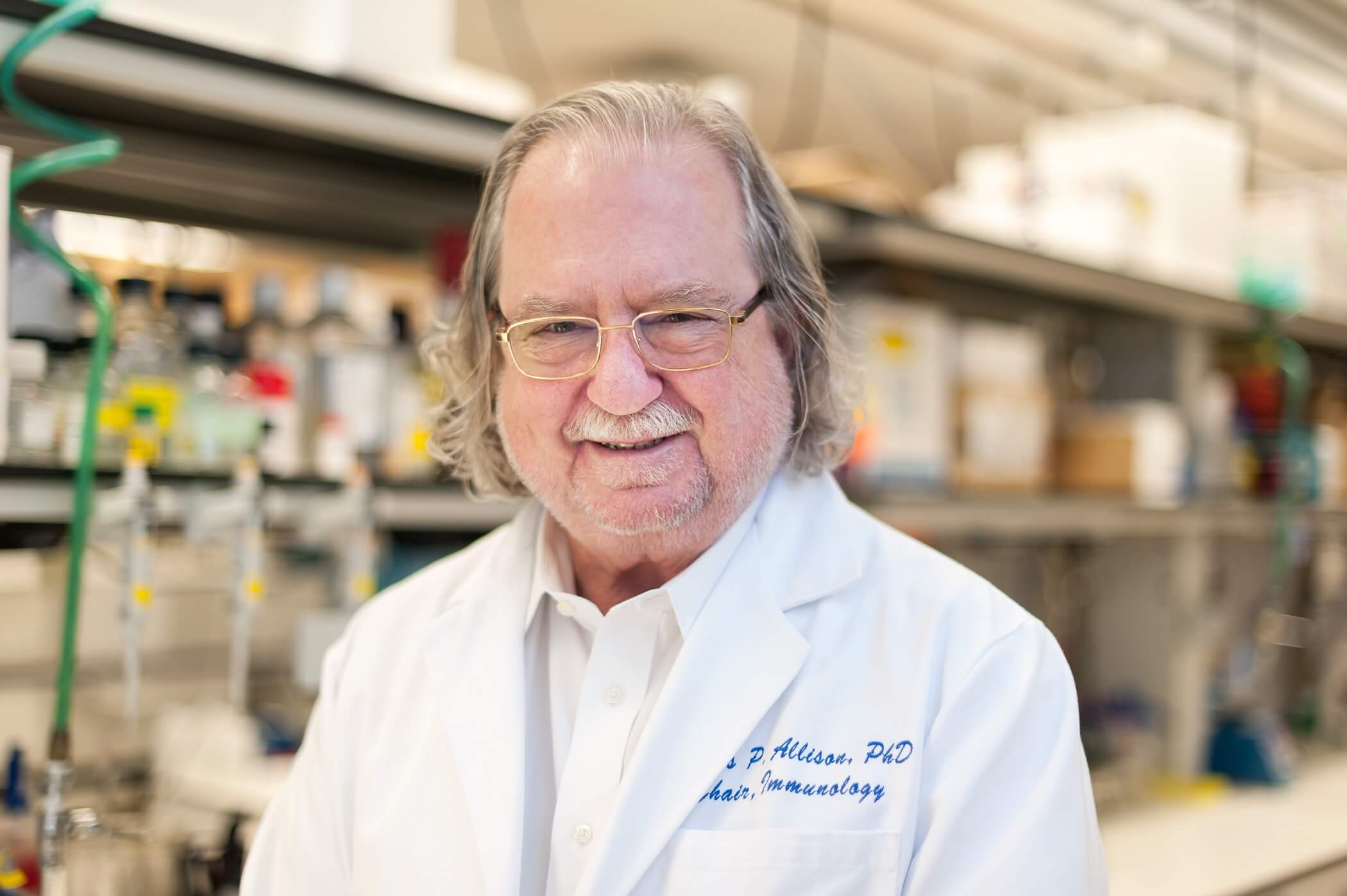

MD Anderson immunologist James P. Allison, Ph.D., named Nobel laureate

James P. Allison, Ph.D., an immunologist at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, was awarded the 2018 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine jointly with Japanese immunologist Tasuku Honjo, M.D., Ph.D. on Oct. 1, 2018 for the discovery of cancer therapies that stimulate the immune system to attack tumor cells.

“I’d like to just give a shout-out to all the patients out there who are suffering from cancer, to let them know that we are making progress now,” Allison said during a news conference broadcast on a live feed from New York City, where he is attending a Cancer Research Institute conference. “The reason I’m really thrilled about this is that I’m a basic scientist. I did not get into these studies to try to cure cancer. I got into them because I wanted to know how T-cells worked. … I’m lucky enough as a basic scientist to see my work actually end up, 20 years later actually, really helping patients.”

Allison, 70, studied a protein that puts the brakes on the immune system. He recognized that releasing the brakes meant that immune cells would be free to attack tumors. Honjo, 76, of Japan’s Kyoto University, discovered a protein on immune cells that also serves as a brake, but through a different mechanism.

“Allison and Honjo showed how different strategies for inhibiting the brakes on the immune system can be used in the treatment of cancer,” the Nobel Assembly at Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm said in a statement. “The seminal discoveries by the two laureates constitute a landmark in our fight against cancer.”

‘No instant gratification’

Allison said he remained in “a state of shock” several hours after the news.

“I was told by the Nobel committee when I was called this morning that this was the first prize they’d ever given for cancer therapy,” he said. “I want to thank a long line of students and post-doctoral fellows and colleagues at MD Anderson and UC Berkeley and Memorial Sloan Kettering over the years.”

Later in the news conference he added, “Science is a long and frustrating road. … There’s no instant gratification. … You’ve got to be comfortable with a lot of failures to get there.”

Allison explained how his research has driven cancer treatment closer to a cure.

“There are, built into the immune system, these inhibitory circuits that stop the immune system at a certain point so that it doesn’t hurt normal tissues, but that also keeps it from attacking tumor cells as effectively as the T cells might. So we found a way to temporarily suspend the brakes and let them take off,” Allison said. “After many years of resistance, I think the cancer field has begun to accept immunotherapy now as the fourth pillar—along with radiation, surgery and chemotherapy—of cancer therapy. What we have to look forward to is that, unlike the other three, immunotherapy can be used in combination with the other three. I think that what we are looking forward to is combinations in the future—not just of multiple checkpoints—but of checkpoints with radiation, checkpoints with chemotherapy, checkpoints with genetically targeted small molecule drugs. I think that … it’s not going to replace all those others, but it’s going to be part of the therapy that essentially all cancer patients are going to be receiving in five years or so—and they’re going to be curative in a lot of patients.”

Disabling the brakes

Born in Alice, Texas with a father who was a “country doctor,” Allison said his research was motivated, in part, by the deaths of loved ones.

“I’ve had a lot of cancer in my family. My mother passed away from lymphoma when I was 10 years old and she’d had radiation therapy, and one of her brothers died of lung cancer and had chemotherapy. I saw the ravages of those kinds of treatments. As I got into immunology … it was always in the back of my mind—it wasn’t the reason I was doing the work, but whenever I could, I would take a rest from thinking about the problem and look at our data and say: What does this tell me that I could use to treat cancer?” Allison explained during the 30-minute news conference. “It was one of those moments when we figured out that CTLA-4 was the brakes on the immune system. Well, let’s just disable the brakes and see if it that would allow the immune system to attack cancer—and it did.”

Allison is professor and chair of the department of Immunology and the executive director of the Immunotherapy Platform at MD Anderson. He holds the Vivian Smith Distinguished Chair in Immunology and serves as deputy director of the David H. Koch Center for Applied Research of Genitourinary Cancers in the Department of Genitourinary Medical Oncology. He also is a director of the Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy, a consortium of experts—including Allison and Sharma—from the nation’s leading cancer centers, including MD Anderson. The immunotherapy platform is part of MD Anderson’s Moon Shots Program, an ambitious effort to more rapidly reduce cancer deaths and suffering by developing advances in prevention, early detection and treatment based on scientific discoveries.

The Nobel Assembly announced Allison and Honjo as the medicine laureates at 11:30 a.m. Sweden time (4:30 a.m. Houston time) before international members of the press and an online live feed. About the same time, 5:30 a.m. in New York, Allison received a call from his son delivering the news before Nobel officials. Shortly after, colleagues showed up at Allison’s hotel room with champagne to celebrate with him and his wife, Padmanee Sharma, M.D., Ph.D., a professor of Genitourinary Medical Oncology and Immunology in the Division of Cancer Medicine at MD Anderson. She and Allison are longtime collaborators in immunotherapy research. A 2017 profile in The Washington Post dubbed them a “cancer-fighting power couple” and noted that “Allison has battled early-stage melanoma, bladder and prostate cancers.”

‘Time is right’

During an interview in Sweden immediately after the Nobel announcement, German immunologist Klas Kärre—a member of the Nobel Committee for Physiology or Medicine—responded to a question about Allison finally receiving the award after being discussed as a potential laureate for some time.

“Time is right,” Kärre said. “The first approved drug based on this treatment came in 2011 and patients have been treated for seven years now and we can see the long-term outcome and it’s very convincing and considered, really, a big step in the fight against cancer.”

Allison developed an antibody to block CTLA-4, which turned into the drug ipilimumab, used to fight metastatic melanoma. Ipilimumab, now known as Yervoy, showed unprecedented results and was approved in 2011 by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

In 2014, the FDA approved the drugs Keytruda and Opdivo, which inhibit another checkpoint molecule, PD-1, for the treatment of metastatic melanoma. (PD-1 is the protein Honjo discovered in 1992.) In 2015, Opdivo was approved for lung cancer treatment.

Allison said he has been professionally friendly with Honjo since the 1980s. In 2014, the pair jointly won the inaugural Tang Prize for Biopharmaceutical Science for their research leading to cancer immunotherapy.

TMC News spoke to Allison in 2015 about the emergence of immunotherapy and in 2017 when tech billionaire Sean Parker gifted $250 million to form the Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy.

MD Anderson created a website for its first scientist to become a Nobel laureate and issued a news release along with a timeline of Allison’s accomplishments.

The Nobel Committee announcement also included Allison’s affiliation with the San Francisco-based Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy. Allison and Honjo will share a $1 million prize. Each will receive a medal and diploma in Sweden during a Dec. 10 ceremony.