Bracing for a Deficit of Doctors

The exodus of baby boomers from the workforce has begun and, with it, the retirement of tens of thousands of physicians.

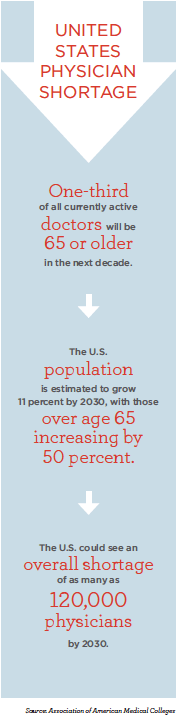

The United States could see a shortage of as many as 120,000 physicians by 2030, according to a recent report published by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). Fueling the shortfall is population growth, an increase in the number of aging Americans and the retirement of doctors.

Should doctors work longer? Should they retire at 65? And what does the exodus mean for other physicians and patients?

“We actually need physicians to stick around longer,” said Barbara Bass, M.D., executive director of the Houston Methodist Institute for Technology, Innovation and Education (MITIE) and president of the American College of Surgeons. “We are anticipating major shortages in general surgery, orthopedics and urology in the next decade or two as the current crop of physicians retire.”

A 2016 study published in the Annals of Family Medicine found that primary care physicians who retired from clinical practice between 2010 and 2014 were 65 years old on average.

Bass recommends finding ways to keep retirement-age surgeons in good practice for a longer period of time. One suggestion: fewer hours.

“We come to work at seven, go home at seven, and you couple that with a few nights of being on call and being up all night, it really takes its toll,” she said. “It’s one thing to stay up all night when you are 22, but when you are 62, it’s really hard.”

Our work does demand a certain degree of physical performance and fitness—whether that is just standing for a long time, visual acuity or manual dexterity.”

In a study released by American Medical Association Insurance— “The 2014 Work/Life Profiles of Today’s U.S. Physician”—researchers found that 21 percent of responding physicians aged 60 to 69 worked fewer than 40 hours per week, but another 20 percent of the same age group worked more than 60 hours per week. Across all ages, nearly half the physicians surveyed said they would prefer to work fewer hours.

Still, a national movement that supports older doctors working fewer hours has yet to take root.

Tests and teaching

Some have suggested that physicians who hope to work past age 65 might benefit from regular testing to gauge their mental and physical acuity. Others counter that, although no mandatory evaluation process for aging physicians exists in the U.S., board certification and hospital regulations help ensure that patients receive the best quality of care.

“The closest thing really has to do with re-credentialing—that has to happen at all hospitals on a two-or three-year basis,” said Savitri Fedson, M.D., associate professor in the Center for Medical Ethics and Health Policy at Baylor College of Medicine. “To maintain hospital privileges to do a certain procedure, you have to have demonstrated that you have done a certain number of procedures in the last two years with an acceptable complication rate.”

In addition, she said, physicians with board certification receive continuing education in their specialty and keep up with advances in technology, patient safety and more. A “board-certified” physician is dedicated to providing top-notch patient care via a rigorous, voluntary commitment to lifelong learning.

Some physicians are able to shift into academic roles in their later years, but that’s not a viable option for the majority.

“One of the things that happens in academic centers is that as people get older and you try and get them out of clinical responsibilities, they certainly have a huge wealth of knowledge and would be some of the best teachers for medical students,” Fedson said. “But that is not a financially feasible model the way our health care is set up, because the reimbursement for teaching is not done to the same extent that reimbursement is done for procedures and, therefore, it is hard to justify salaries.”

Brain drain

Experts anticipate a massive brain drain in health care as baby boomers leave medicine.

“The concern for me is the loss of wisdom that comes from people who are still practicing at a good level,” said Joseph Kass, M.D., Baylor professor in the departments of Neurology, Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and in Medical Ethics and Health Policy. “Maybe their hand skills aren’t as amazing as they used to be, but they still have a wisdom and a knowledge—not just because they have been doing this for 40 years, but because they have kept up with developments, they have perspective and know history and the human mistakes of yore.”

Intergenerational learning also offers tangible benefits to younger physicians immersed in technology, said Kass, who is also Baylor’s associate dean of Student Affairs.

“There is an art to medicine that does get lost because of technology,” he said. “Technology is great—we want the imaging, we want all of these things to diagnose better, but there is still the laying of hands on a patient and being able to take a really good history. Those are the things we stand to lose.”

Managing patient expectations

The AAMC estimates a shortfall of between 14,800 and 49,300 primary care physicians by 2030.

“Part of the problem with that is that we still have a relative deficit of primary care physicians,” Fedson said. “We have made up some of that with the wider acceptance of physician extenders—the use of well-trained nurse practitioners and physician assistants to help, but I think the impending shortages of physicians will mean that it will probably be more difficult to do some things.”

Certainly, patients will need to be more realistic about where they receive their care.

“Part of the expectation in this country is that ‘I have a right to see whatever specialist I want to.’ So patients think if you have joint pain, you should go see an orthopedic surgeon. That is not necessarily the case,” Fedson said. “If you have joint pain, once you exclude trauma or break or anything mechanically wrong, you could see a physical therapist instead. That gatekeeper can be beneficial for patients and streamline appropriate care for patients with a dwindling number of sub specialists.”

Managing physician expectations

Aside from the impact retiring baby boomers will have on the health care industry, it is worth considering what retirement will mean for physicians who have been practicing for close to half a century. Physicians contemplating retirement should reflect on their hobbies and interests before making a move, Fedson said.

“In medicine, we get positive reinforcement nearly every day. People thank you for what you do and while we don’t explicitly need the thanks, I think everyone likes to know that what they are doing has value,” she said. “You go from working in a field where you know, on some level, what you are doing makes a difference. And then not to have that, suddenly, can be very, very difficult from an emotional well-being standpoint.”

As long as aging physicians can complete their duties, Bass said, keeping them around and delaying retirement could be beneficial.

“If their performance is strong and capable, let’s figure out ways to keep them on board as opposed to ways to shut them down,” Bass said. “We need capable, happy, healthy physicians that can provide care to our patients. As we look ahead to the anticipated shortage of physicians, if we can find a positive way to extend one’s career—even on a part-time basis—that is going to be a good thing.”