Baylor Employee Shares Story of Childhood Trauma in Hopes of Helping Others

On Sept. 5, at the Baylor College of Medicine Grand Rounds for OB/GYN physicians, residents and medical students, guest speaker Gregory Williams turned off all the lights in the auditorium and began a short video clip.

The video showed images of children with hands over their mouths, hunched over and ashamed. A brooding cover of “The Sound of Silence” by heavy metal band Disturbed played while statistics flashed on the screen: every 98 seconds, someone is sexually abused in the U.S.; 1 in 4 girls have been sexually abused; 1 in 6 boys.

Williams, a member of the senior administrative team in the department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Baylor, was one of those boys.

“It took me approximately 35 years before I ever told anybody,” he said after the video ended. “And being 55 years old, you can start figuring out that my life was shattered.”

Williams kept the lights off through the remainder of the lecture, but his message Wednesday morning was one of encouragement, of gently persuading victims to speak. He explained that his song choice for the video was intentional, that, as the song goes, his own silence was like a cancer.

“The longer I kept it down in me, the more it started to fester, the more it started to develop into things that I didn’t want it to develop into,” he said, citing OCD and PTSD, among other conditions and symptoms.

Sharing the secret

But one day, three years ago, he unexpectedly blurted out his secret during a presentation.

“You know, I was abused as a kid,” he recalled saying in front of a large audience.

It was the first time in his entire life that he’d ever told anybody.

As soon as he said it, all of his fears rushed forward. “I thought, nobody’s going to like me, nobody’s going to care about me, everybody’s going to shun me, nobody’s going to talk to me anymore, my family is going to alienate me, I’ll be totally alone,” Williams said. It was the refrain he’d been telling himself for decades.

At age four, Williams’ first recollection of being raped, his father threatened to take him from his family and put him up for adoption if he told anyone. Williams also suffered from shame and guilt—common feelings among survivors of abuse.

But after that seminar when he’d shocked the room with his deepest, darkest secret, more than 20 people were waiting in line to speak with him. In those conversations, he remembered, every person said, “I’ve never told anybody either.”

Now, Williams wants to help others through their own trauma of sexual abuse by telling his story. He travels the country for speaking engagements and has recently published a book about his past.

“I wrote this book and, since it’s come out, I’ve talked to over six doctors on our floor that have come to me, closed the door and said, ‘Greg, this happened to me, too,’” Williams said. “I’ve had several admins come to me and tell me the exact same thing.”

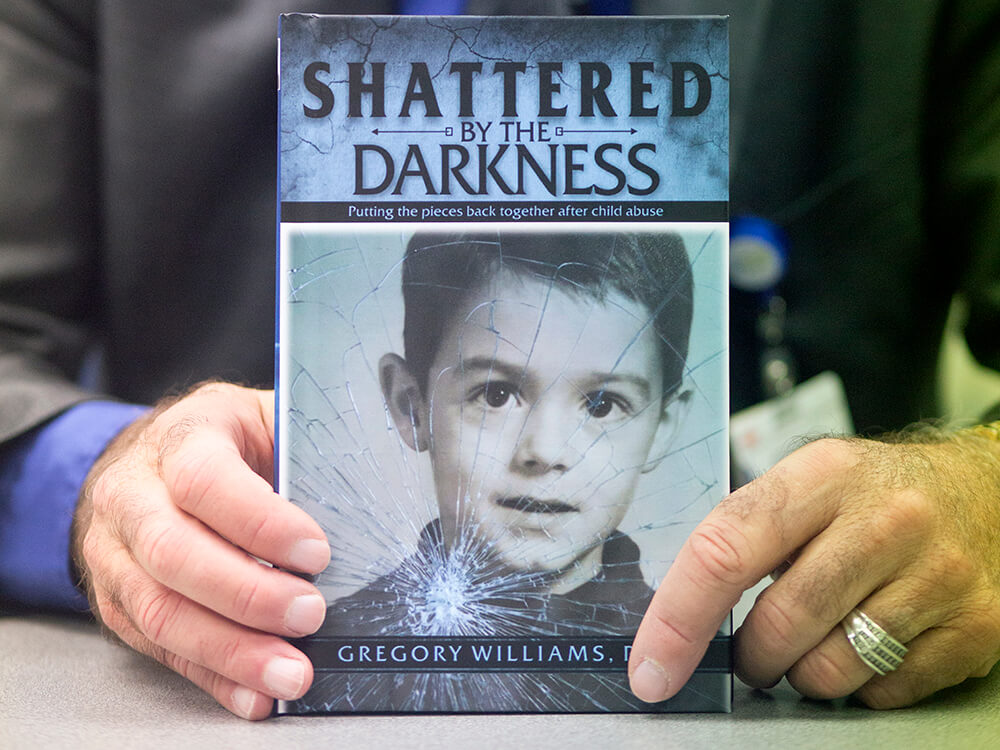

Titled, Shattered by the Darkness, the memoir describes Williams’ life at the hands of an abusive father.

“I don’t want it to happen to my grandson. I don’t want it to happen to anybody that I love. I didn’t want it to go another generation,” Williams said. “I’m using the rest of my life for this one mission: to go around all over the country and to speak and tell people that no matter what happens to you in the negative side of life, you have the opportunity to turn it into something positive. And the only way to be able to do that is to be able to start talking about it. If you don’t let it out, you’ll never get help.”

Gregory Williams holds a copy of his book, Shattered by the Darkness.

Heart trouble

The effects of sexual abuse last a lifetime. Williams still has nightmares in which he wakes up screaming after reliving particularly horrendous episodes, and sundown almost always brings on suffering.

“That’s why I come to work at 4 o’clock in the morning now,” he said. “I hate night. I hate going to bed. I hate evening-time. I just prefer to stay up.”

Williams cited research to illustrate how a negative childhood experience like sexual abuse can have a lifelong impact on physical health. Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) have been linked to risky health behaviors, chronic health conditions and mortality, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The risk of these outcomes increases with the number of ACEs a child has suffered.

Williams himself experienced this firsthand. In 2010, doctors discovered his heart was failing and he was in urgent need of major surgery. But they were also puzzled; all signs had pointed to a healthy cardiovascular system and doctors couldn’t understand why one valve had just stopped working.

Later, another doctor told Williams that internalizing so much childhood trauma had left a toxic trail in his body that had affected his heart.

“I was one of those statistics that the ACEs talk about,” Williams said, adding that he had scored an 8 out of 10 on an ACEs questionnaire, with 10 being the worst.

At the end of the lecture, Williams asked if there were any questions. A doctor in the audience raised her hand.

“Did a physician ever ask you if you’d been abused? We’re taught to ask if there are any problems with alcohol, smoking, drugs—but did anyone ever include in that list abuse?”

“No,” Williams answered. “I never recall a physician asking me that—ever. Even to this day.”

“Say that louder,” the doctor requested, “so that all the students in the room can hear.”