Mentalization at Menninger

Kula Moore, a psychiatric rehabilitation specialist at The Menninger Clinic and a board-certified art therapist, combs through an oversized folder of her patients’ latest work to share with colleagues.

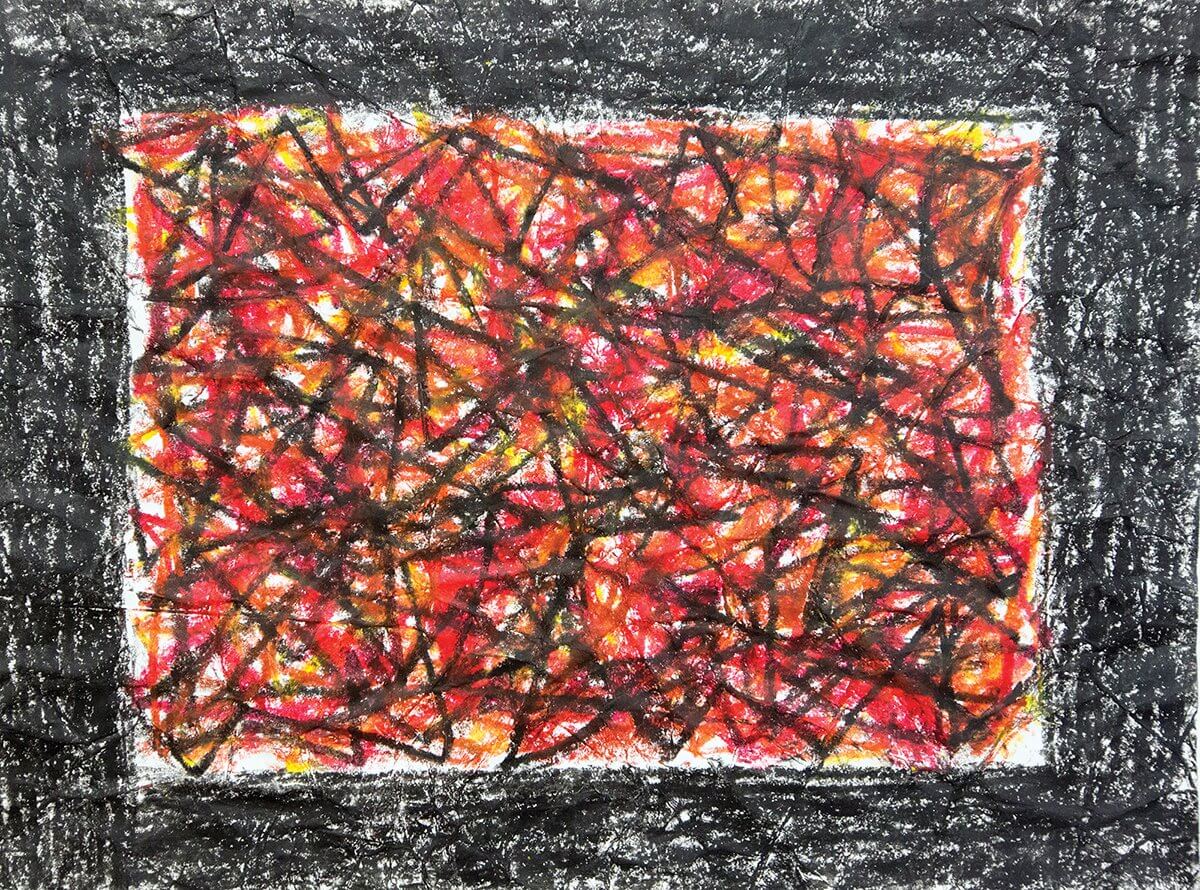

She lays out brightly-colored abstract drawings and flaming red pieces made with chalk pastels, markers, crayons and pencils on the surface of a table. Moore presents each drawing and shares what each patient was trying to express when they made each piece.

“Art therapy is not about making masterpieces or things that you would necessarily hang on your wall,” Moore said. “A lot of times the art people make is very personal and it deals with treatment issues.”

Moore’s evidence-based, mentalization art therapy groups at Menninger help her patients externalize their thoughts, emotions, feelings and relationships. Mentalizing helps patients connect with other people in their therapy group, the therapist and even with family and friends.

Moore starts each session by giving her groups a prompt. Sometimes she asks them to express emotions in a landscape, or she might invite them to represent a relationship that is important to them.

“Artwork is an accelerant to that process because they don’t expect to put as much on the page as they do,” Moore explained. “With our words, we can filter and we can hide and we can do more image control verbally than we can visually with art materials and paper. I think sometimes it is unexpected for patients—they don’t expect for it to be as powerful as it is.”

In addition to her roles at Menninger, Moore is the founder of Art Therapy Houston, an organization that provides art therapy and counseling services to children, adolescents and families. She is also working with a group from the United Kingdom to publish research that focuses on the difference between how patients understand visually as opposed to how they understand verbally. One of Moore’s patients in Menninger’s Compass Program, which serves individuals ages 18 to 30 who are struggling to manage the transition from adolescence to adulthood, found that art therapy unlocked feelings she had no other way of releasing.

“She came in with a lot of difficulties internally. She had a lot of difficulty expressing her emotions,” Moore said.

The patient made her first drawing with chalk pastels, filling an 8 x 10 page with fiery blasts of red, yellow, orange and black, surrounded by a large black border.

“She said that is how her anger feels, that it can destroy anything it touches and she is afraid of it and to let it out, afraid of it destroying her relationships and other people,” Moore said. “I remember perfectionism was a huge thing for her, so the fact that she pushed herself to use a more loose, messy material was a big step.”

After five weeks of working with the patient, Moore saw a shift in her art. Moore showed the group her patient’s final piece—a drawing made with markers that also included lightning bolts she added, using collage.

“The collage, I think, is interesting because it shows depth, how she used the cut and paste method,” Moore said. “It was consistent in what she was trying to represent—that there is complexity, that it’s not all bad. She can have moments of light where she feels like herself and lively again, which is what these bolts represented, versus the dark, which still exists. She’s still struggling, but the fact that she could recognize the moments where she could be fine, I think, is helpful.”