Musician Plays Flute During Deep Brain Stimulation

Anna Henry raised the flute to her mouth, took a deep breath and recalled from memory the notes of one of her favorite classical concertos. Her fingers flitted over the keys as she slowly, carefully played each note. After she finished the song, the room burst into applause.

But this wasn’t a typical concert performance.

Henry, 63, was lying on her back on an operating room table surrounded by doctors and nurses. Part of her scalp was peeled back to expose her skull. Surgeons had drilled two nickel-sized holes into her skull and inserted a tiny 1.3 mm-thick electrode into both sides of her brain where her thalamus is located.

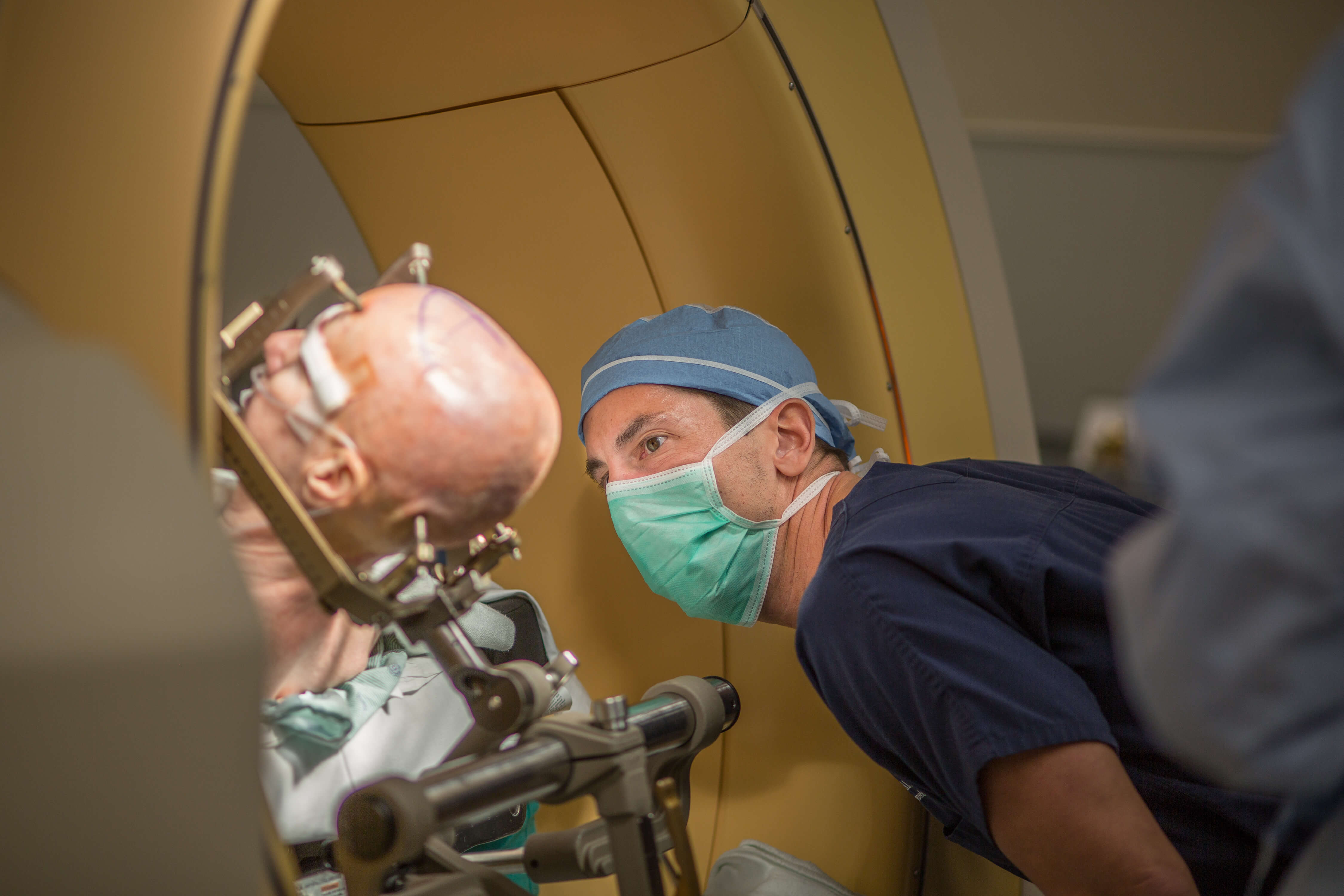

The surgical team prepares Henry for surgery.

The surgical procedure, called deep brain stimulation, is used to treat the neurological symptoms of certain movement disorders. Surgeons implant tiny electrodes into the brain to deliver a constant electric current that significantly reduces movement and neuropsychiatric issues.

“Deep brain stimulation is a really fantastic tool in how we can modulate a perturbed, dysfunctional system in the brain and make it more normal,” said Albert Fenoy, M.D., neurosurgeon with the Mischer Neuroscience Institute at Memorial Hermann-Texas Medical Center and UTHealth, who specializes in the procedure.

‘Resetting’ the brain

Although the exact science and mechanisms behind its therapeutic benefits are unclear, deep brain stimulation has proven to be highly effective in “resetting” the brain and eliminating tremor.

“Why these patients have all these issues, like Parkinson’s disease, is because a circuit is abnormally functioning. It’s oscillating at a rate that, for whatever reason which we still don’t know, is wrong. It’s causing the detriment that they’re experiencing,” Fenoy explained. “By overriding that abnormally oscillating circuit with high frequency stimulation, you can override that dysfunction and train it to be a more normalized firing pattern.”

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved deep brain stimulation to treat four conditions: essential tremor, Parkinson’s disease, dystonia and obsessive compulsive disorder. Because of its effectiveness, researchers are studying deep brain stimulation as a possible intervention for chronic pain, post-traumatic stress disorder, major depression and other conditions.

Fenoy checks in on Henry before he and his team begin the surgery.

Deep brain stimulation has been shown to have a high success rate for patients whose conditions no longer respond to medication.

“A lot of patients, unfortunately, go into denial and say, ‘I don’t need brain surgery for my tremor.’ Every patient who has surgery says, ‘I’m so glad that I had it.’ But they have to overcome that early [hesitation],” Fenoy said. “All patients have success. Our goal is to greatly reduce their tremor. Will it be 100 percent gone? I don’t guarantee that for any type of surgery, but the tremor will be 70 to 80 percent better than it is now. That is a vastly significant improvement.”

A better state

For Henry, deep brain stimulation was her final hope. She knew early on in her childhood that she would inherit her father’s shaky hands. He suffered from a disease called essential tremor, the most common movement disorder.

Henry began experiencing tremors in her left hand and fingers in junior high. It started with a slight quivering in her left hand, but as the years went on, her tremors intensified to a point where she could no longer perform simple everyday tasks with her dominant left hand, such as writing her name, drinking soup or sewing. The combination of beta-blockers and an epilepsy drug prescribed by her doctors—propranolol and primidone, respectively—no longer worked and caused muscle weakness and eye problems.

“It was frustrating to see that [control] disappear gradually and just to realize that my control wasn’t what it used to be,” she said.

Worst of all, Henry’s tremor prevented her from doing what she loved the most: playing the flute. Henry is the principal flutist in the Big Spring Symphony and a music teacher who has been playing the flute since she was 11 years old.

“The ability to express things through my music in a way that I’m used to isn’t there anymore, no matter how hard I practiced,” Henry said. “I love practicing, but I’ve gotten to the point where I don’t like practicing because I’m not getting anywhere with it. It’s not making me improve like it always had.”

Henry’s neurologist in Lubbock approached her four years ago about the possibility of treating her tremor with deep brain stimulation, but the idea of brain surgery was frightening to her.

“At that point, I didn’t want anybody poking a hole in my brain,” Henry said. “As the symptoms got worse, the proposition of doing that got a little less daunting, especially when it came down to keeping the tremors for the rest of my life, letting it get worse and giving up playing—or going for it.”

She flew to Houston with her husband, Bob, on Monday, March 26. The following morning, she met with her surgical team and prepared for the operation. Henry, who arrived at the hospital with short, strawberry blonde hair, had her head shaved and was fitted with a stereotactic frame to secure her skull in place before she was wheeled into the operating room.

Her surgery unfolded in two parts: first, surgeons inserted the electrodes into the thalamus, which modulates and fine tunes movement; and second, they implanted a rechargeable battery pack in her chest that will last up to nine years before it will need to be replaced.

Henry’s anesthesiologist administered a local anesthesia to the scalp to numb the pain, but Henry was wide awake for the first part of the surgery. Fenoy and his surgical team made an incision across the front of her head and another on the side. They gently peeled back her scalp and used a special drill to bore through the 7.1 mm of bone in her skull. Fenoy then inserted the stimulating electrodes through the holes to her brain and applied the electric current.

Fenoy marks on Henry’s shaven scalp where he will make the incision.

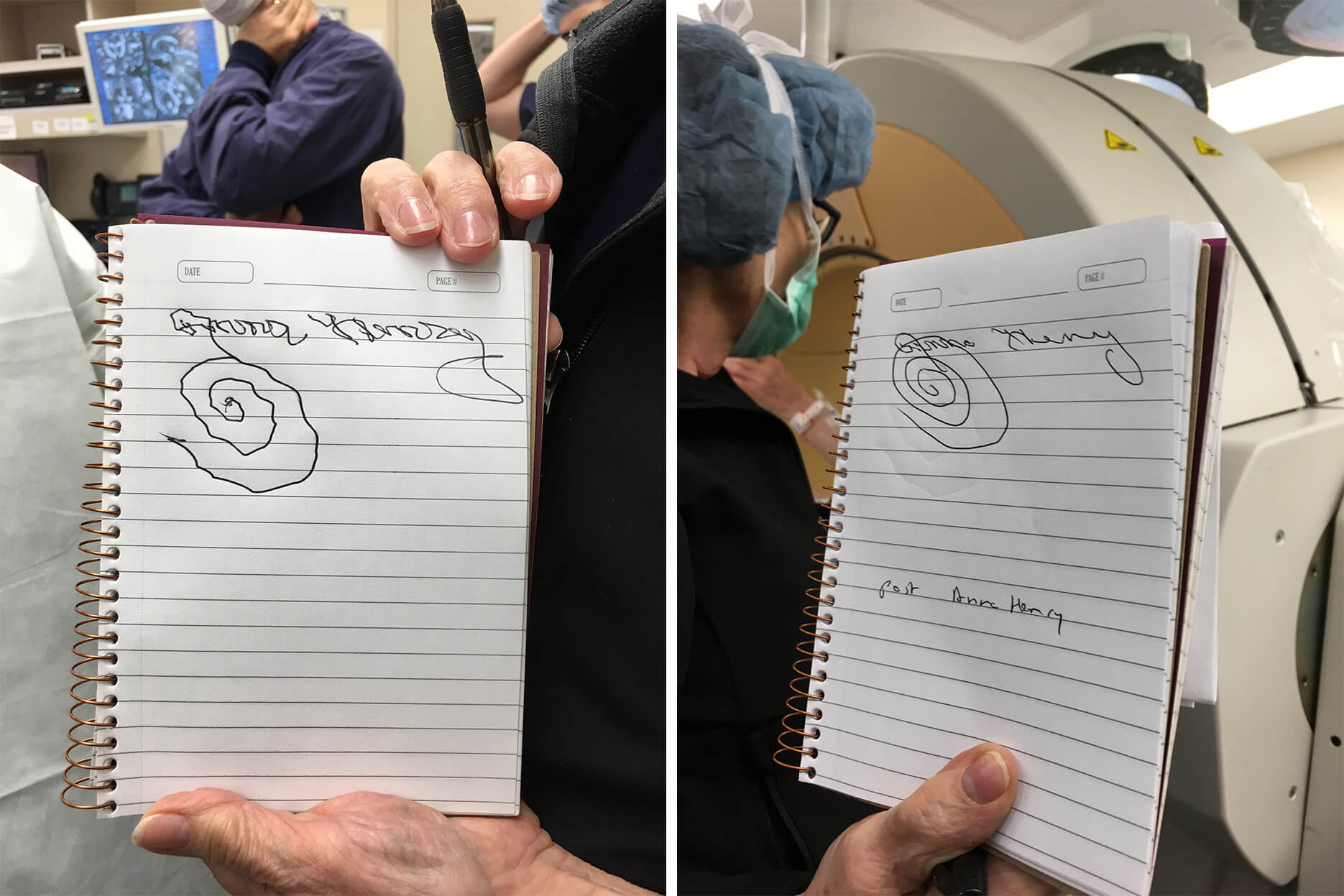

The result was like flipping a switch. Prior to the surgery, Henry’s neurologist, Mya Schiess, M.D., of the Mischer Neuroscience Institute at Memorial Hermann-Texas Medical Center and UTHealth, ran a few motor control tests. Henry could barely sign her name, let alone hold a pen. When handed a cup of water, her hand shook so intensely that the water splashed inside the cup.

But after the electrodes were placed in her brain and the thalamus was stimulated, Henry’s hand was still and stable, without a single detectable tremor. When she signed her name a second time, each pen stroke was smooth and clean. Her handwriting was legible for the first time in decades.

Before and after: Henry’s handwriting test before the deep brain stimulation (left). Henry’s handwriting test after the deep brain stimulation (right).

Henry plays the flute while on the operating room table during her deep brain stimulation surgery.

The surgical team handed Henry her flute to test if her hands were stable enough to play. As she remained on the operating bed, she lifted her flute to her mouth and treated everyone in the operating room not only to a sweet melody, but the joy of seeing her tremor disappear.

“[Deep brain stimulation] works amazingly well,” Schiess said. “If you have a tremor that is truly interfering with hand function, lifestyle, head or voice, honestly, there isn’t a medicine out there that’s going to really put you in a better state.”

For Henry, deep brain stimulation helped her get back to doing what she loves. Although her tremor had interfered with her quality of life and nearly put an end to her musical career, she refused to quit.

“My folks lived through the [Great] Depression,” Henry said. “If there’s anything they taught me, it was that an obstacle is not something that stops you; it’s something you find a way around.”