Correcting a Gene that Causes Blindness

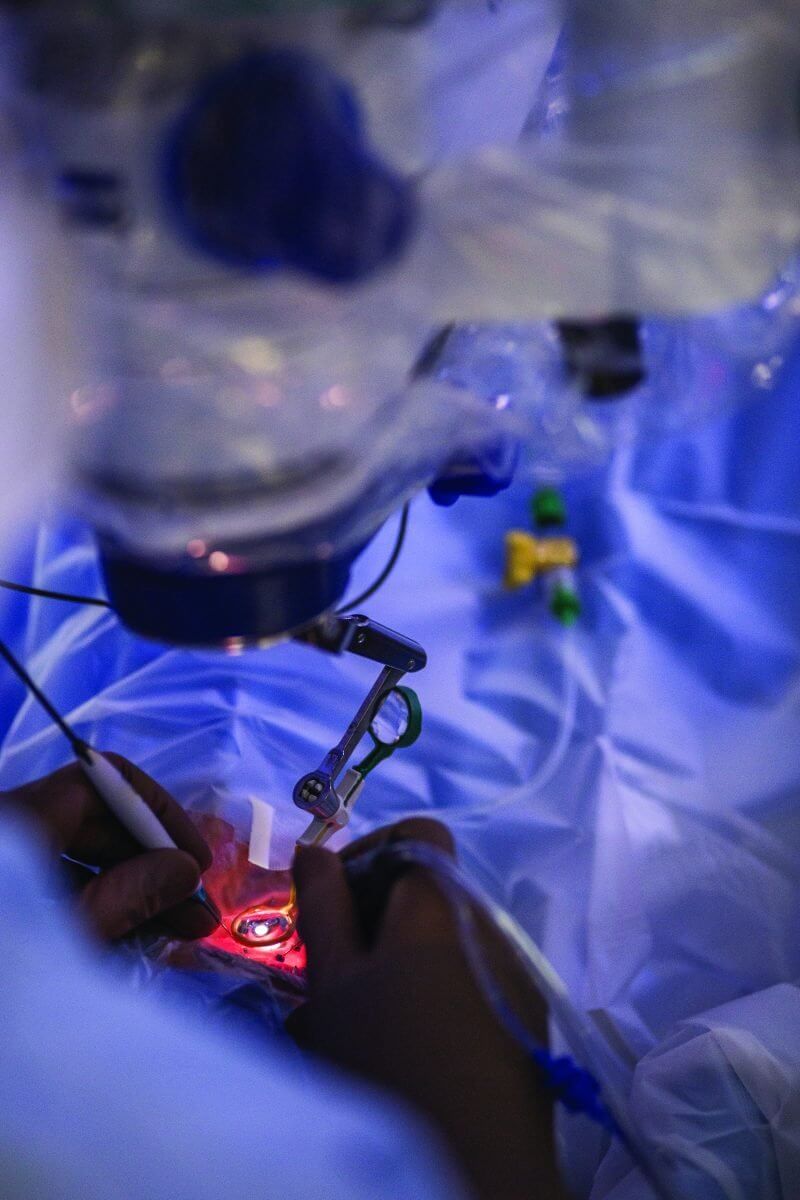

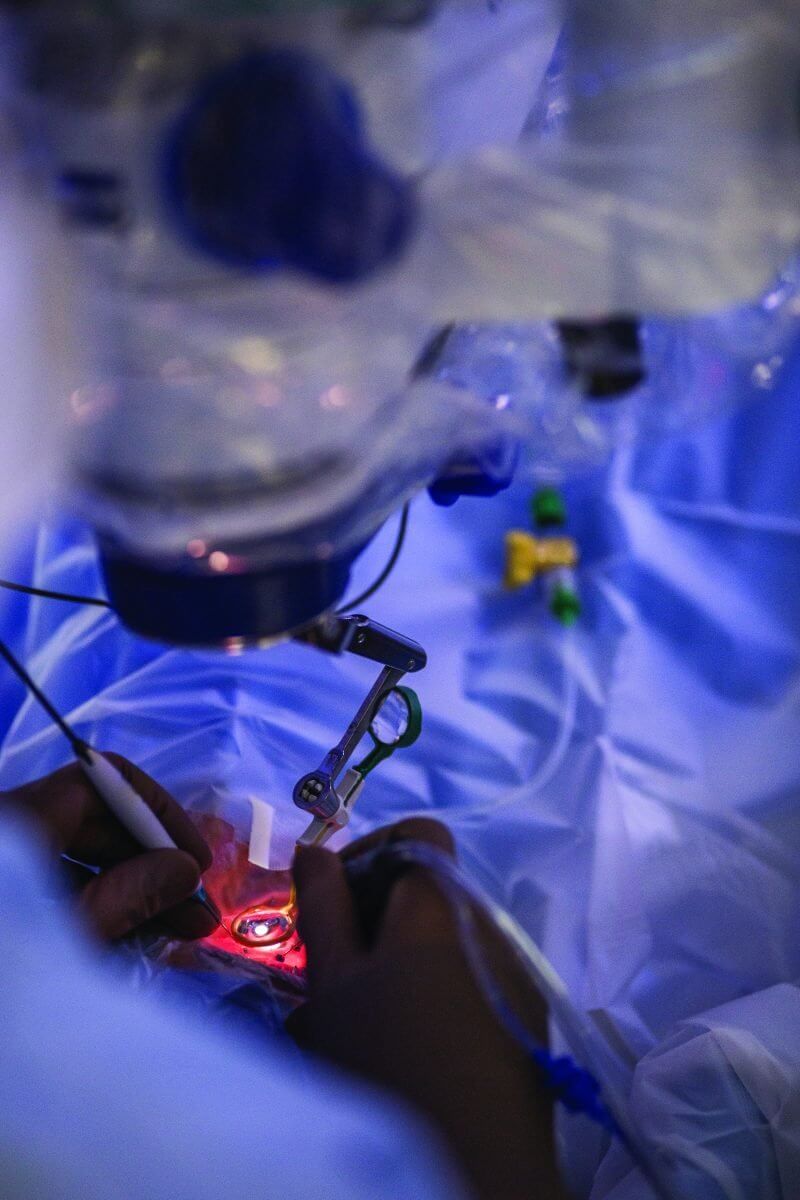

Sixteen-year-old Amanda Martin lay on the operating table under full anesthesia, her body covered in sterile cloths one shade shy of peacock blue. Only her right eye was exposed, the word “yes” scribbled in marker above it—visual verification that it was, indeed, the correct eye. Numbing drops pooled over her cornea and spider-like surgical equipment held her lid wide open in preparation for surgery.

Within minutes, Christina Y. Weng, M.D., assistant professor of ophthalmology- vitreoretinal diseases and surgery at Baylor College of Medicine’s Cullen Eye Institute, would begin a pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) to remove the vitreous gel from Martin’s eye. For Martin, the procedure would create space for an artificial lens, but a PPV is also part of the ground-breaking genetic therapy recently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat a rare form of blindness—the country’s first directly administered gene therapy approved to target a disease caused by mutations in a specific gene.

‘A remarkably beautiful ballet’

Pharmaceutical company Spark Therapeutics got the green light in December to market Luxturna, a drug injected directly under the retina to correct a mutation on a gene called RPE65. One of the most common conditions associated with the mutation is Leber congenital amaurosis, or LCA, which is characterized by severe visual impairment at birth. Until now, no treatment options were available.

“It’s a very exciting time for the retina world right now,” Weng said. “It’s taken giants in the research and clinical worlds to really consolidate their efforts toward developing something that could finally treat disorders that we once thought were untreatable.”

The mechanics of vision are multifaceted. Light meets the cornea, travels through the pupil, the lens, and finally penetrates the gelatinous material in the center of the eye, called the vitreous, to reach the retina—a membrane lining the back of the eye that converts light information into electrical signals for the brain to understand.

“There is a lot of complexity in how the retina does that—there are lots of moving pieces,” said Timothy Stout, M.D., Ph.D., director of the Cullen Eye Institute. “Typically, these are proteins that are expressed in the retina that allow this conversion from light information to electrical information to take place. There are hundreds of thousands of moving parts that do that. It’s a remarkably beautiful ballet.”

But as with everything in the human body, one small mutation in the genes that code these protein parts can wreak havoc on the whole system. How that translates to vision impairment depends on the gene affected.

“You can have some mutations that are in certain moving parts that are so absolutely deleterious that you can’t see light from day one of life,” Stout said. “Then, on the other end of the spectrum, there are problems with proteins in your retina that may be so mild that maybe when you’re 70 or 80 you may have some issues, but other than that, you’re good.”

What typically happens in Stout’s clinic is that parents notice a problem—their child fails a school screening or can’t see well when the lights go out or has trouble distinguishing colors. That information, he said, helps guide him toward which moving parts might be problematic, though some form of gene sequencing is required to make a conclusive diagnosis.

“I might find out that the reason Johnny can’t see well is because he’s got a mutation in both copies of gene ‘X,’” Stout said. “So what we’ve started to say is, ‘If Johnny’s not seeing because he doesn’t have a normal copy of the gene ‘X’ and can’t make protein ‘X,’ what if we put a normal copy of that gene into a virus and then put the virus near the cells that are affected, infect those cells with the virus, and then have that normal protein be expressed?”

And that’s exactly what they did for RPE65.

Fourth-grade graduation

Leber congenital amaurosis is so rare it is thought to affect only a few thousand individuals in the U.S. But it presented a perfect opportunity for gene therapy trials because it is caused by a relatively straightforward mutation. The disease typically manifests when both parents carry and pass on a copy of the mutation, an inheritance pattern known as autosomal recessive.

“What we’ve done is we’ve put a normal copy of the human RPE65 gene into an adeno-associated virus, which infects the right cells inside the eye but doesn’t cause disease,” explained Stout, who worked on the research trials that led to the development of Luxturna. “Viruses have evolved over millions of years to be gene delivery systems. They’re really, really good at doing that. Adeno-associated viruses are expressed for a long time—we believe that they express forever—which is something we want for an inherited disease. The virus goes into the cell, infects the cell, then it’s over.”

That, in a nutshell, is gene therapy. Once the corrective copy of the defective gene infects the abnormal cells, genetic information should start processing correctly. In the case of RPE65, that means making a once-missing protein.

The surgical procedure to inject the drug requires special technical skill. Currently, the therapy can only be administered at eight U.S. sites; Baylor College of Medicine is one of those sites and four surgeons there are trained to perform the surgery.

The first step is the pars plana vitrectomy. Surgeons make micro-incisions through the wall of the eye and use a special hollow needle housing a blade whirring 2,500 times a minute to remove the jelly-like vitreous, which is too viscous to simply suction. Once the PPV has cleared a path to the retina, an even smaller needle—about the circumference of four strands of brunette hair—is used to inject a small blister of Luxturna just underneath the retina. That injection is loaded with the adeno-associated virus carrying the corrected RPE65 gene.

Clinical trials showed extremely promising results, although Stout and his fellow researchers did observe that the treatment worked best in younger patients, perhaps because their cells carrying the RPE65 gene had not yet reached a point of no return.

“You probably can’t treat dead cells, right? Once you’re dead, it’s kind of game over,” Stout said. “But what we don’t know is where in the disease process those cells become fated to never be repaired. So we’re expecting that there’s going to be a spectrum of susceptibility for gene therapy for different diseases and different genes.”

Still, many of his patients were able to see for the first time in their lives, and the trial’s success has paved the way for the development of genetic therapy treatments for other inherited diseases.

“One of the young girls I treated in Oregon did so well that she invited me to her fourth-grade graduation,” Stout said. “She was in the Washington State School for the Blind and she invited me to graduation because they were kicking her out. The school threw a big party—they’d never been able to kick anybody out before.”

Baylor is currently working on additional trials involving other genetic mutations that cause ocular disease, but will continue the research and surgeries that are literally shedding new light on their patients’ lives.

For Martin, who had the lenses in both eyes removed at age two due to complications from congenital cataracts, that means not wearing glasses for the first time ever. To celebrate, her aunt took her to buy a pair of Ray-Ban aviators, but she’s most excited about going back to Disney World. A roller coaster junkie, Martin can now ditch the special goggles with lenses as thick as magnifying glasses.

“I’m excited, because I’ll actually be able to see the rides this time,” she said.