After the Flood: Health Dangers Left in Harvey’s Wake

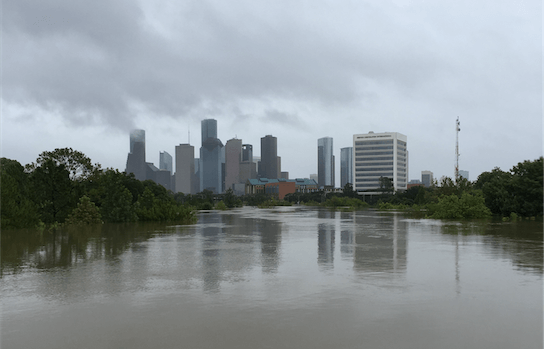

After five days of catastrophic flooding, Houston is just beginning to assess the extensive destruction Tropical Storm Harvey left in its wake. Even after Harvey’s floodwaters recede, health risks remain.

Floodwaters introduce a slew of health concerns, including infections, mosquito-borne diseases, allergic reactions and respiratory problems, according to Peter Hotez, M.D., Ph.D., dean for the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine.

“We actually have an interesting body of literature now of the infectious disease problems that people faced after Hurricane Katrina more than a decade ago,” Hotez said. “There are some similarities—because it is the Gulf Coast region—between what we saw in Katrina and what we can expect in Harvey, so it’s instructive to look at that.”

Infections and wounds

After Katrina, there were several cases of skin infections from staphylococcus, including an antibiotic-resistant staphylococcus, called methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus or MRSA. Additionally, more than 20 illnesses and five deaths were caused by wounds contaminated with vibrio vulnificus, a type of flesh-eating bacteria that can be found along the Gulf Coast.

“What that means is people who have been exposed to floodwaters, especially if they have wounds, want to keep those very clean and get medical attention for them,” Hotez said.

Because floodwaters can introduce bacteria from soil, dust and manure into the body through punctures in the skin, it’s important for people who have been wading to wash themselves thoroughly and to stay up to date on tetanus shots to protect against disease, Hotez said.

“You don’t need to do a mass immunization of tetatnus. The recommendation is that you should get a tetanus booster every 10 years,” he said. “If you’ve not had one recently, then go and get one—no rush. If you have a wound, then you probably want to accelerate that and get one as quickly as you can.”

Breeding site for mosquitoes

Hurricane Harvey, which was downgraded to a tropical storm Tuesday, descended onto the Houston area on Friday, inundating the city and its neighboring regions with heavy, persistent rain. Floodwaters displaced thousands of people and continue to submerge homes in many areas. Experts say it could take days to weeks for the water to clear.

Standing water becomes an excellent breeding site for mosquitos, particularly for Culex mosquitoes that transmit West Nile virus and the Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes that transmit dengue, Zika and chikungunya.

“That’s going to be something we’re going to have to look after, whether we’re going to see an uptick in any of those mosquito-transmitted viral diseases in the coming weeks,” Hotez said.

And it may take some time for these diseases to develop. The number of reported cases of West Nile neuroinvasive disease nearly doubled in Louisiana and Mississippi a year after Hurricane Katrina hit.

Even after floodwaters recede, the damage left behind in homes can threaten the health of residents if mold and bacteria grow in water-damaged walls and floors. Exposure to mold can cause severe allergic reactions, respiratory symptoms and asthma, and can pose a more serious threat to immunocompromised individuals.

Prevention

As the mosquito population increases in the next few weeks, it’s important to use insect repellent that contains DEET to reduce the risk of contracting any mosquito-borne illnesses.

Overall, Hotez said, the best thing to do is to “have a low threshold for getting medical attention.”

“If you start developing symptoms of diarrheal disease or respiratory infections or if you have a wound that looks suspicious, then you want to get that taken care of,” he said.

In the aftermath of Harvey, public health and emergency preparedness become the center of discourse for city and state officials, but Hotez said preventative measures for infectious and tropical diseases in the Gulf Coast are still disregarded.

“If you look at where we live on the Gulf Coast, it represents our nation’s most vulnerable area to disease,” Hotez said. “Everybody’s focused on the two coasts, especially the urban centers in Boston, New York, Silicon Valley and Los Angeles, and we forget everything in the middle. Yet the Gulf Coast, because of the factors of poverty, climate change, rapid urbanization and human migrations, I think that creates this perfect storm that makes this region particularly susceptible. It’s not really happening on a national level to recognize the vulnerability of this region.”