Solutions: Treating Parkinson’s

The uncontrollable twitching began in Steve Sawyer’s big toe, on his right foot, about nine years ago.

Sawyer, then 49, went to see a neurologist, who thought it might be early-onset Parkinson’s disease, a degenerative brain disorder that initially affects motor skills, causing tremors,stiffness, slowness of movement and impaired balance. As the disease progresses, patients may develop cognitive problems, psychiatric alterations and dementia.

Steve Sawyer

Sawyer was referred to Joseph Jankovic, M.D., director of the Parkinson’s Disease Center and Movement Disorders Clinic at Baylor College of Medicine, who prescribed the typical regimen of medication, starting with a couple of pills a day. But Sawyer quickly discovered that as the disease progressed, more and more medication was required to control his tremors.

“Plus, the medication gives you sides effects, like drowsiness, so you have to take a medication to offset that,” Sawyer said. “It is a bad spiral you go down. Initially, it is a slow hill, but it seemed like overnight that it got pretty bad.”

Indeed, things got so bad that Sawyer began to refer to Jankovic not as his Parkinson’s doctor, but as his “pill doctor.”

Though it is hard for him to admit, Sawyer considers himself pretty lucky with the disease, because he only has bad tremors on his right side—in his leg and hand—and he can mask them by keeping his hand in his pocket. He was so good at hiding the symptoms of Parkinson’s that he didn’t reveal his diagnosis to his grown children until a year ago, around the time he decided to pursue a new treatment.

“They were getting started in life, and I didn’t want them to be burdened,” Sawyer explained. “I didn’t want people knowing and looking at me any differently. When I decided to do the new treatment, I started letting people know, like my family and neighbors. It was interesting to have them ask what I was up to, and to tell them I was going to have brain surgery.”

It was Jankovic who told Sawyer about an opportunity for a new treatment with Joohi Jimenez-Shahed, M.D., an assistant professor of neurology and director of the Deep Brain Stimulation Program at Baylor. Sawyer became the first CHI St. Luke’s Health-Baylor St. Luke’s Medical Center patient to receive an updated form of deep brain stimulation, a surgery reserved for patients with movement disorders who are no longer responding well to medications.

The deep brain stimulation surgery occurs in two stages. In the first stage, wires outfitted with electrodes are inserted into the brain. In the second stage, the wires are hooked up to a battery pack—a pacemaker-like device inserted into the chest—that controls the stimulation, Jimenez-Shahed said.

This type of procedure has been done for more than 20 years, but a new device from St. Jude Medical makes it possible to control the stimulation from the doctor’s office using a wireless iOS software platform on an iPad mini device. Doctors had not been able to do this before. Patients can also use an iPod Touch device controller to discreetly manage their symptoms.

“The device allows us more programming capabilities, like adjusting the stimulation to steer the electrical current right where we need it to go,” Jimenez-Shahed said. “That is important, because if the current is too close to adjacent brain structures, it might also deliver stimulation there and cause unwanted side effects.”

Sawyer liked the idea of a treatment that targeted the areas where his tremors occurred. The problem was that the device did not yet have U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval, so even though he had met the criteria to be a candidate, he had to wait. But not for long. Last October, the deep brain stimulation system received FDA approval. Today, five months after the device was implanted, Sawyer and his doctor continue to figure out how best to adjust the equipment settings.

Jimenez-Shahed said the battery pack will eventually need replacing, but can last between three and five years, depending on the amount of current.

Sawyer has cut back on all his medications, taking just one tablet four times a day. He used to take three tablets four times a day and one tablet at night to sleep.

The deep brain stimulator allows patients to better control their symptoms, reduce the “off” time when the drugs aren’t working as well and eliminate dyskinesia, or difficulty performing voluntary movements, Jimenez-Shahed explained. Overall, it helps patients feel less dependent on the medication.

That’s good for Sawyer, who continues to work as an architect at a construction consulting company. He said when the illness was at its worst, it was tough to work, especially because his job is stressful.

“Stress and Parkinson’s don’t go well together,” Sawyer said. “This procedure has been a benefit to me, though my doctor did tell me if I wanted to keep working, I needed to get a less stressful job.”

‘Early diagnosis means good treatment’

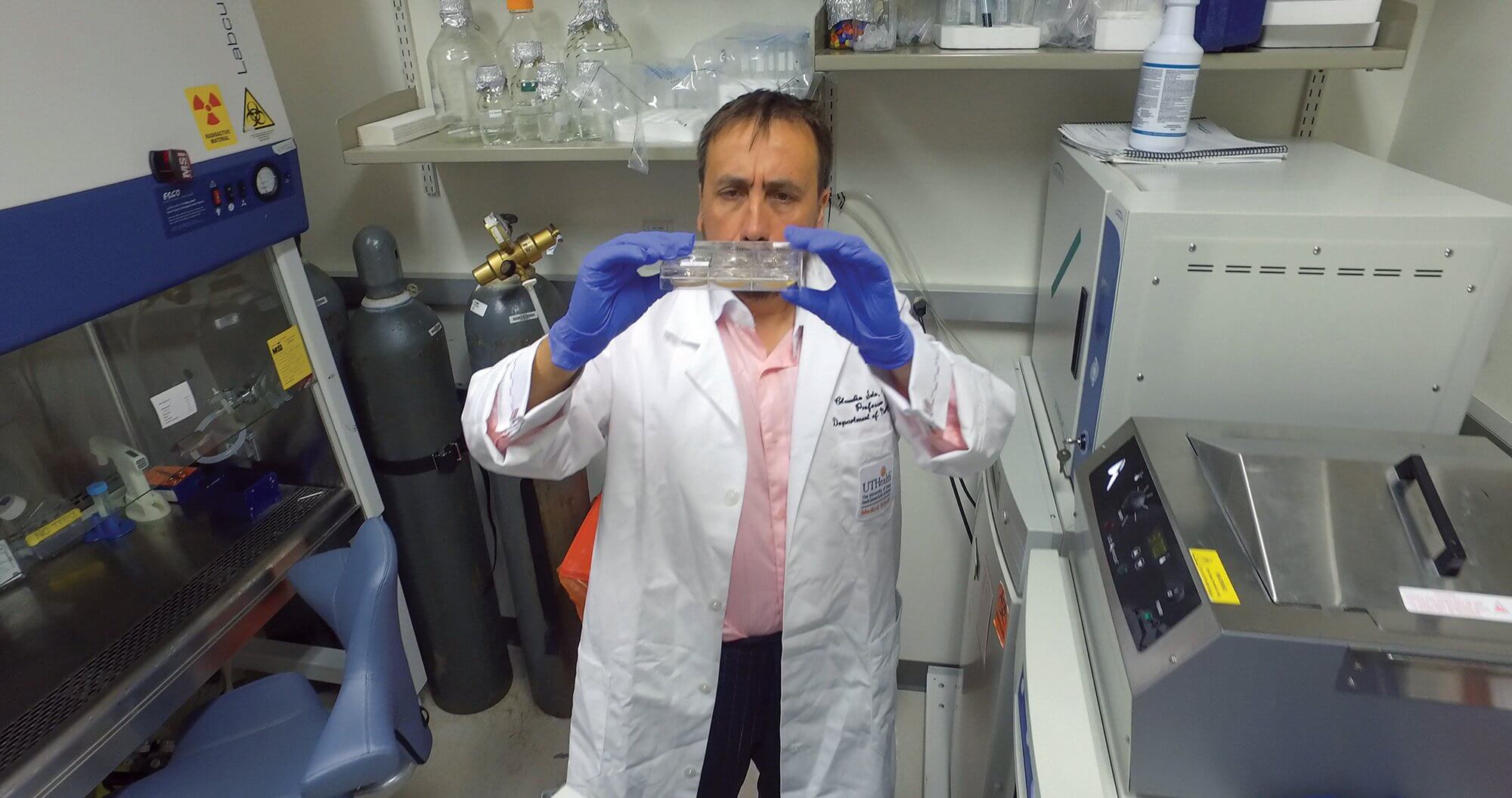

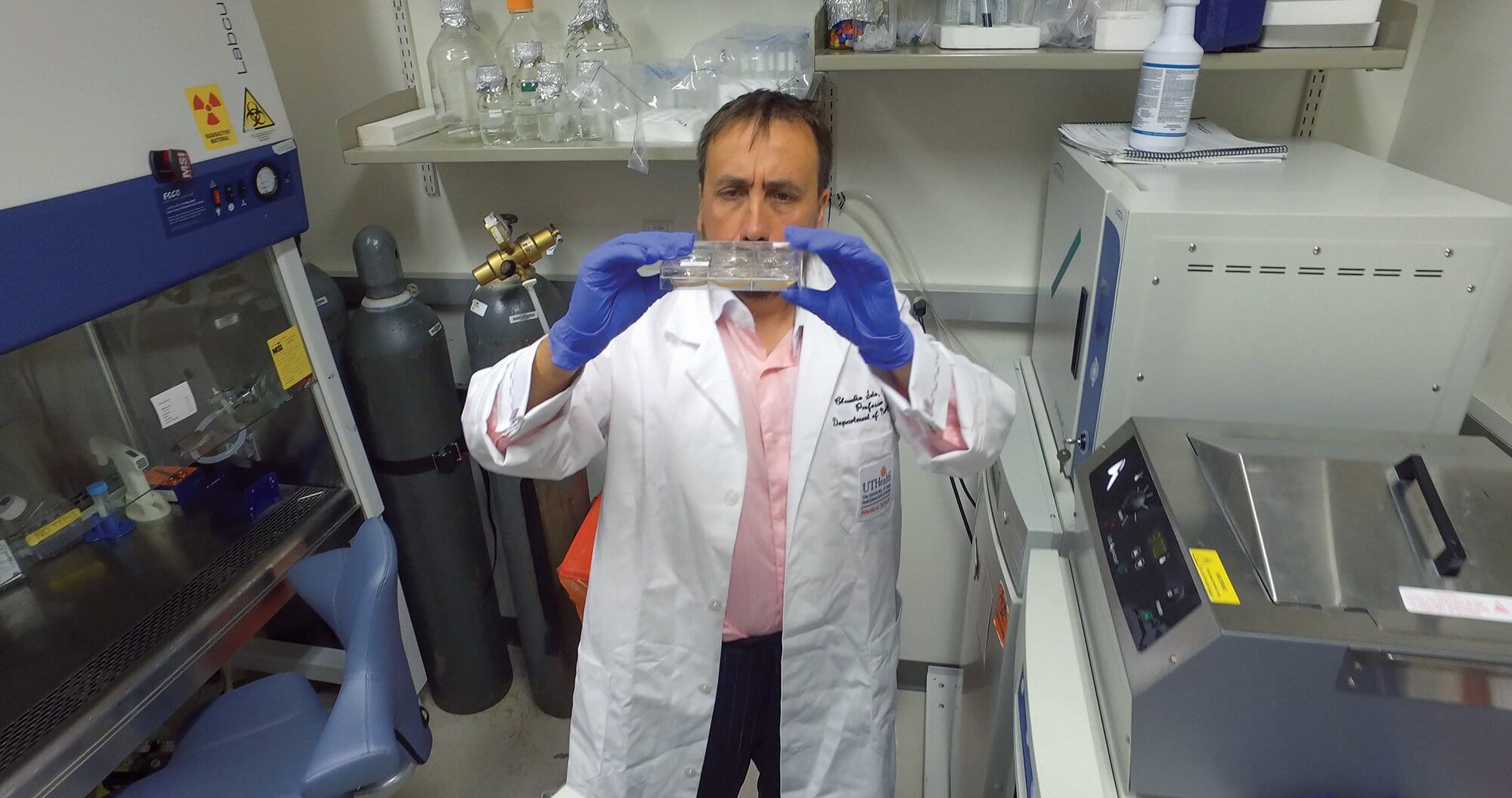

Meanwhile, scientists at McGovern Medical School at The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth) are working on early detection of Parkinson’s disease, so patients like Sawyer can get a diagnosis long before any tremors or twitches send them to the doctor.

UTHealth scientists are studying abnormal proteins associated with Parkinson’s disease in cerebrospinal fluid and trying to develop a biochemical test to diagnose the disease.

There are no current laboratory or blood tests that have been proven to help diagnose Parkinson’s, said Claudio Soto, Ph.D., a professor in the department of neurology and director of The George and Cynthia Mitchell Center for Research in Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Brain Disorders at UTHealth. By the time patients manifest symptoms, he said, their brains have already seen significant degeneration.

“At the clinical phase of Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases, there is substantial damage in the brain that is often irreversible,” Soto said. “The brain can cope with a large amount of damage, and only when brain degeneration becomes major is when people start getting symptoms.”

Soto wants to identify the brain damage responsible for Parkinson’s disease earlier. There are some experimental treatments for Parkinson’s out there, he said, but many scientists and clinicians say they have failed in clinical trials because the treatment started too late.

“Early diagnosis means good treatment,” Soto said.

His research, funded in part by grants from the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research, was published in the Dec. 2016 issue of JAMA Neurology, a journal of the American Medical Association. The first author of the paper is Mohammad Shahnawaz, Ph.D., of McGovern Medical School at UTHealth.

Using technology developed by Soto that has been shown to find abnormal proteins (known as misfiled proteins) associated with diseases such as Creutzfeld-Jacob and Alzheimer’s, researchers detected very small amounts of the misfiled proteins circulating in cerebrospinal fluid.

The hope is that someday, a simple test will be able to detect these misfiled proteins in blood or urine.

“We envision in the future a noninvasive test that someone would take during their 40s or 50s that would be as common as a test to check for cholesterol level,” Soto said. “The doctor would test for Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease, tell you if you have the abnormal protein and recommend what to do about it.”