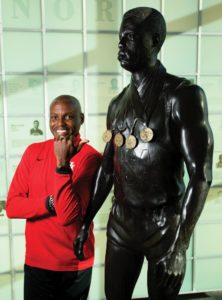

TMC Spotlight: Carl Lewis

Track and field star CARL LEWIS won nine Olympic gold medals and eight World Championship gold medals over his 17-year career. Lewis spoke with Pulse about his family, his “terrible” jogging, and coaching at his alma mater—the University of Houston.

You were born in Birmingham, Alabama in 1961. Tell me about your parents and their involvement in the Civil Rights Movement.

They ended up in Montgomery, Alabama, after college. My mother became friends with Rosa Parks. When the bus strike happened, it just so happened that my parents were teachers and had a car. Because of that, it was all hands on deck. If you have a car and if you see someone walking to work, pick them up. That’s what drew them into it.

Then we became close with Dr. King and the family. We were part of the church and my brother was baptized by Dr. King. We went through that period. When they moved to Birmingham, we moved to Birmingham, where my sister and I were born.

We were at the frontlines. My parents were marching and doing all the things that were happening at that time.

Then in 1963, we moved to Willingboro New Jersey, where they were just finishing up a Civil Rights lawsuit for equal opportunity housing. Willingboro was founded as an all-white community. There was gentleman, named W. R. James, who sued to get in and that was part of the equal opportunity housing act.

Civil Rights has always been a part of my upbringing, and we just happened to go places where it was put in the forefront.

I can tell your parents played key roles in shaping who you are today.

I think my father was a lot like the people of his era. He wasn’t the kind of guy who would say, I love you.’ I don’t even remember him saying it more than a couple of times in my life, but he showed it. Dad had your back. He was really strict on discipline and structure. We always said, ‘Bill Lewis did not play.’ He did not like bad kids. He not only understood how to raise a young man (and daughter, like my sister Carol), but also a black man. I didn’t realize it until I got older and especially when I had my son while he was growing up that there was a difference. We’re starting to see there’s a different way to raise a black man, unfortunately, than other men. I didn’t realize it then, but Dad was very good at that because he and my mother were coaches in the community and they were teachers.

My mother was a visionary. When she moved to New Jersey, she wanted track and field. In the ‘60s, they mainly had softball, field hockey and basketball, but they didn’t have track and she was like, “Girls should have a track program too. Why do the boys have track and girls don’t?” That’s how the Willingboro Track Club started because she was like, “If they won’t put it in the schools, then I’m going to start my own club.”

Our summers evolved around the track program. I lived in New Jersey, 40 minutes from the shore, but I never went one time in my life. I did not know it existed because we were at track meets or this or that. They were down eating saltwater taffy and I was at track meets eating cold chicken.

You ended up attending the University of Houston. What made you choose to become a Cougar?

There were three powerhouses: Villanova, Tennessee and Houston. I originally wanted to go to UCLA, but that didn’t work out. It came down to these three.

When I came to Houston on a visit, it was the worst. I got here, a guy took me around and it was boring. He just talked my ear off. He wanted to talk about the past, but I wanted to talk about the future.

The head coach asked me to meet him at the track office Sunday and he would take me to the airport. I get there and the track was a dirty track. It was just ridiculous. I’m saying, ‘This is such a waste of my time.’

When I went into that meeting with the head coach, he pulled out some videos and we watched them in his office in a rickety old building. He’s talking about the long jump, he’s talking about the jumpers, and I’m like, ‘Wow, this guy understands the long jump!’

He said, ‘You’re tall. You’re fast, I think you can break the world record and be an Olympic champion.’ That was it. That’s what I wanted to hear, but I didn’t know it until I heard it.

You’re back at the University of Houston as a coach. How do you incorporate that “be the best you can be” attitude into your track and field program?

Renu Khator [UH president and chancellor of the UH system] and I have become very good friends. We’ve won conference every year I’ve been here. Every time I see her, she says, ‘How many Olympians?’ And that’s the visionary in her. She’s seeing the program beyond college. Being someone who wasn’t born in America, she sees the world in a different way.

I only want to recruit a kid who wants to become an Olympian. That’s it. That doesn’t mean you’re going to be, but I want someone with that vision.

We’re an Olympic-based program, so if you’re not thinking of that—whether you make it or not—you don’t fit here.

My greatest accomplishment, I’d say, is the longevity in my sport. Jesse Owens, who is a huge idol of mine, didn’t have a chance to go back to the Olympics or he would have been Athlete of the Century. I think it’s the fact that I went 10 years in a row without losing a long jump against anyone. Through that period, it was three Olympic Games. I won four Olympics in a row, and was No. 1 in the world over 10 years in the sprints. These are things that may not happen again. It’s the longevity, the fact that I improved as I got older because I had to to meet the challenges.

You became a vegan in 1990. Did it help your athletic performance?

I wanted to keep my weight down, but I did it by not eating. I would skip breakfast every day, skip lunch most days, and eat dinner. It was just unhealthy. I started doing some research on what I had to do to maintain a better diet. It came out to vegetarian and vegan diet. The biggest challenge wasn’t shifting to that diet because that was easy for me. It was changing my mindset to eat more. I had gotten so used to turning away breakfast because I’d gain weight, so early on, I was calorie deficient and listless. I was eating 2,500 calories a day, that’s it. We were training, so we were burning thousands of calories.

It took a while for me to get used to eating three vegan meals a day. After that, I really loved it because I could eat these huge meals and snacks. My chef became so creative in the way she cooked, cooking vegetarian lasagna with spinach and soy cheese. But I’ll eat meat sometimes. I don’t trip out on it.

You say that you don’t like running, but as an Olympic sprinter and long jumper, that seems kind of counterintuitive.

No, I don’t like jogging at all! Actually, I’ve never liked distance running, never liked jogging. Coach Tom Tellez at UH used to always laugh and say, “It’s good, because you’re the worst looking jogger. You look terrible jogging!”

You tried to run for state Senate in New Jersey in 2011, but were disqualified because officials said you did not meet the four-year state residency requirement. What did you learn from that experience?

I ran because I wanted to make a difference. In South Jersey, there were a few things. Number one, I was at a restaurant and denied service. It was bizarre to me because I had been around the world, but five miles from my home, some woman said she’s not serving me. I thought, Well, that story needs to be told.’

Someone also needed to fight for pension issues and plans. South Jersey is one of the most segregated public school systems in America. I grew up there, had a wonderful time and loved it. Then I moved to Houston and to California. I traveled to over 200 countries and started seeing the world.

I started saying, ‘Wow, this place is so backwards,’ so I wanted to make a difference.

I wasn’t afraid to stand up to the government at the time. Everyone was like, ‘Oh my God!” But I just said, ‘Dude, are you kidding me?’ I would have been an outspoken senator.

I ran and they fought me at the state level, from Governor Christie all the way down, and kept knocking me off the ballot. Finally, I realized that the reason I was running was because the people who were there weren’t stepping up to have the community they wanted. It was probably the community they were happy with, but it wasn’t a community that I was happy with. I finally saw it this way: If everyone says one thing and you say something else, maybe it’s you. I realized it was me, so I moved back to Houston. I didn’t leave pouting. I just was in the wrong place.

As someone who stays incredibly busy, how do you unwind?

I love nature, so I garden. I love my yard. We cut down every single tree in the yard and replanted 75 plants. I enjoy doing that. If there’s a tree that needs to get cut, I’ll cut it. But I won’t cut grass. I hate cutting grass; I had to do it when I was young.

I love to ride my bike and zip through the city, especially Houston, where they have so many bike trails now. This is the great thing about Houston: it’s an international city, so let’s step our game up. The parks are beautiful. We already know the culture’s there and the museums and the theater scene are fantastic. I know they say it’s hot and everything, but we want to make the outdoor opportunities as great as we can, like Memorial Park.

I love history, too, whether it’s reading about history or watching documentaries. Matter of fact, we used to have documentary Sundays. Growing up, it used to drive my son crazy. He admits it wasn’t that bad, though.

What’s the best nickname you’ve ever been given?

I have an Indian spiritual name. It’s Sudhahota, but a lot of people call me Sudha. It means ‘unparalleled sacrifice for immortality.’ Sri Chinmoy, the Indian spiritual leader, gave me that nickname. He’s passed away now, but we were friends for years and he gave me that name back in 1983.

And the worst nickname?

That came from people in track. When I was a kid, I had the nappiest hair. Kids used to call me “spit” because my hair was so nappy growing up. It was horrible. Back in the ‘70s, I used to put those blowout kits in my hair because, if I didn’t it’d be really nappy and lint would catch in it. People would be like, ‘It looks like people spit in your hair.’

Carl Lewis was interviewed by Pulse reporter Shanley Chien. This interview has been edited for clarity and length.