Dr. Winston’s Playbook: Leland Winston Chose Medicine Over Football, But Never Really Gave Up the Game

On Sunday afternoon, Jan. 11, 1970, more than 80,000 sports fans gathered at Tulane Stadium in New Orleans to watch the Kansas City Chiefs face off against the Minnesota Vikings for Super Bowl IV.

It had rained that morning and heavy clouds hung in the sky. The area was under a tornado watch and temperatures dipped into the low 60s. But devoted spectators—bundled up in sweaters and coats—still filled the stadium. The excitement was palpable.

The game began. Play after play, tackle after tackle, players from both teams pushed through the mud, struggling for a win. Ultimately, a combination of short passes and trick plays devised by Chiefs head coach and offensive coordinator Hank Stram led the Chiefs to victory over the Vikings, 23-7.

“That’s it, boys! Yaaaa-ha! Haa-haa! Waahh!” Stram cheered fanatically after Chiefs wide receiver Otis Taylor scored the game-clinching touchdown.

Stram and the rest of the players swarmed towards Taylor in celebration. But one football player—a young man who had an offer to play for the Chiefs—wasn’t among them. Leland Winston was watching the game 380 miles away, drinking beer and eating hot dogs in Galveston, Texas.

Dreams of his grandfather

Leland Winston, M.D., grew up in Lake Jackson, Texas, a small community 57 miles south of Houston where there was “nothing but tiny little towns and woods all around.” His grandfather often visited from North Carolina and took every opportunity to encourage young Winston to go into medicine.

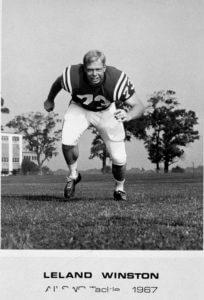

Rice University football player Leland Winston, All SWC Tackle (Photo/Rice Athletics)

“He would come by and tell me at the age of five that I was going to be a doctor,” said Winston, now 70. “I never had any other thought than ‘I’m going to be a doctor. That’s what I’m going to do.’ It was nice growing up knowing what I was going to do.”

Secretly, his grandfather had always aspired to be a doctor, as well, but was denied the opportunity by a wealthy aunt who urged him to become a Presbyterian minister. He eventually became a cowboy instead, but looked to Winston to fulfill his medical dream.

Winston attended Rice University, where he met his wife Pam, and graduated in 1969 with a major in biology. While he excelled in academics, Winston was also a stellar athlete. He had played every sport imaginable as a child, and in college, he was a track and field athlete and a two-time All-Southwest Conference lineman who caught the eye of the pros.

Before he graduated, Winston was drafted by the Kansas City Chiefs to play professional football. The team offered him $11,000 for the first year, an amount equivalent to nearly $80,000 today, but Winston was set on pursuing the dream he shared with his grandfather. He received his acceptance letter to medical school at The University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston in time to decline the opportunity to play for the Chiefs.

Winston still remembers his conversation with Coach Stram: “He said, ‘Well, we’re going to win the Super Bowl this year.’ I said, ‘Great. You do that.’ And they did!”

Still, Winston felt no pangs of regret. He was ready to close one chapter of his life and move onto the next.

“When you play football in college, you’re pretty much playing for your school—at least it was back then,” Winston said. “Once you get to the professional level, it’s different. It’s a business, and I wasn’t interested in going into it. I just wanted to get on with what I wanted to do, which was to be a physician.”

Inspired by his own proclivity for breaking bones from all the sports he played, Winston pursued a career as an orthopedic surgeon. It was a specialty that didn’t teeter on the edge of life and death, and married his two great loves: sports and medicine.

“I like the fact that I can meet a patient, take care of their problems, use my hands to fix it, and they can come back to see me after they’re well,” he said. “I get a charge out of that.”

Part of the family

Once Winston graduated from UTMB with his medical degree, he moved back to Houston to complete his residency at The University of Texas Health Science Center and start his practice at Houston Methodist Hospital, both just half a mile down the road from Rice.

Winston received the game ball award on Sept. 16, 2016, during the Rice vs. Baylor football game for his 50 years of service and commitment to the Rice community. (Photo/Scott Dalton)Houston Methodist Hospital, both just half a mile down the road from Rice.

Although he turned down his chance to join the NFL family, Winston found a different football family and a different Super Bowl stadium.

In 1974, while he was a resident, Winston became a consulting physician for the athletics department at Rice under the supervision of Rice team physician, James Butler, M.D. That same year, the NFL hosted Super Bowl VIII at Rice Stadium, where the Minnesota Vikings lost—again—to the Miami Dolphins.

“He’s not just our team doctor, he’s part of the family here,” said David Bailiff, the current head football coach at Rice. “He’s looking at these kids with these eyes like he’s their dad, and you feel that spirit with him that he just cares so much for these players and coaches and this team.”

In 1990, Winston assumed the role of co-head team physician alongside his friend Tom Clanton, M.D., treating student athletes who are balancing school and sports. It’s a juggling act he knows all too well from his days racing back and forth between the biology lab and the football field.

“He knows what these players are going through academically and athletically, and he really relates well to them,” Bailiff said. “He has an incredible manner about him where he can put them at ease and talk them through what’s happening and what they have to do to get well. There’s this trust and love that we all have in him.”

To this day, Winston can be found on the sidelines at practices and home games, watching over the athletes, ready to treat any injury or ailment. Knee injuries and shoulder dislocations are the most common injuries he sees. Thanks to advancements in modern medicine, they are no longer career-ending injuries, but they still take a toll on the body.

Men’s football claims the largest average annual estimated number of injuries in college sports, according to a 2015 study conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The dangerous high-impact nature of the sport and the possibility for subsequent injuries mean physicians must focus on treating the entire athlete, rather than just taking care of the specific injury when it happens.

Winston treats a Rice football player during practice.

“Sports medicine is about two things: Getting an athlete back into a sport safely, and recognizing what they’re going to be like for the rest of their life so you can counsel them on whether it’s going to be dangerous to keep doing it or not,” Winston said.

Most of the student athletes he treats are not going to make a living playing professional sports, he added, so there’s a moral and medical imperative to consider the long-term mental and physical effects of their injuries.

“They’re going to go out and live a normal life, so we have to look at the long-range plan,” Winston said. “Instead of asking how they’re going to be next season, more importantly, how are they gong to be in 20 years? Are they going to be crippled or not?”

Perhaps not surprisingly, Winston has inspired some athletes to pursue careers in medicine.

David Berken, M.D. a former Rice offensive lineman, is one of the many athletes Winston has treated. Berken sustained multiple injuries throughout his four-year college football career, but thanks to Winston, he continued to play the sport he loves while discovering a newfound passion for medicine.

“He was taking somebody that wasn’t able to continue playing and make them better to the point where they were able to get back out and perform at their original capabilities and potential,” said Berken, now an orthopedic surgeon in Shreveport, Louisiana. “I thought that was the coolest thing he was able to do … for an athlete or anyone in general.”

Because of his injuries, Berken spent a lot of time rehabilitating with Winston, working part time at Winston’s office and talking with him after practices. Berken became inspired by witnessing first-hand the kindness and the care Winston brought to his patients, whom he treated and viewed like family.

“That type of experience isn’t something you always get in health care, but that was always the thing you heard about Dr. Winston,” Berken said. “That’s something Dr. Winston does extremely well, something I’ve taken to try and use in what I do in my patient care.”

Balancing act

Winston greets his daughter, Carol Olivero, and granddaughter, Katie, in the stands. (Photo/Scott Dalton)

Winston has spent long hours and late nights building his own practice and taking care of his Rice athletes. His arduous work paid off, but it wasn’t without some sacrifices along the way, like missing his son’s golf tournaments and games as a kid.

“The hardest thing is balancing everything,” Winston said. “Keeping everything—your job, your interest in the sport, time for your family and your spiritual life—balanced. It’s a tough … act for anyone.”

These days, Winston is constantly surrounded by family: his wife of nearly 50 years, four grown children, 10 grandchildren, Rice athletes and patients. While things could have turned out very differently for Winston had he accepted the offer to go pro, there’s no version of this story in which he’d trade his white coat for an NFL jersey.

“I wouldn’t change a thing, not a thing,” Winston said. “I’m having a great time.”