Anatomy of a Workday

Just shy of 5:30 a.m. on a recent Wednesday, Brennan Roper, M.D., arrives at Memorial Hermann-Texas Medical Center. The first-year resident in the department of Orthopedic Surgery at McGovern Medical School at UTHealth lives less than five minutes from the hospital. He set his alarm for 4 a.m. so he would have time to shower, review anatomy books, and make his daily breakfast: an egg and turkey sandwich on a toasted English muffin. On this particular day, he will not touch food for another 12 hours.

By 5:40 a.m. Roper is bedside, speaking with a patient from his previous day’s rounds. Twenty minutes later, the team convenes for their morning meeting. Residents, nurses and physician assistants are always joined by the on-call attending physicians to review the day’s case list and to discuss diagnoses, doses and expected outcomes.

The human body contains a mighty 206 bones, but there are infinitely more ways to break them. Roper ticks off a list of likely sources: monkey bars, excited dogs, contact sports, slippery tile, upturned rugs, rollerblades, ATVs, cars, baseball bats, and guns. People fall, trip and crash. And the orthopedic trauma team at the nation’s busiest Level I trauma center puts them back together.

A Bloody, Mangled Hand

At 7 a.m. Roper hurries to McGovern Medical School to attend a lecture led by Kyle Woerner, M.D., an assistant professor in the department of orthopedic surgery. Woerner, who specializes in the upper extremities, begins his PowerPoint with a close-up photo of a bloody, mangled hand.

“Can anyone tell if the flexor tendons were cut here?” he asks.

“Definitely,” a student calls out.

Woerner smiles. “Look carefully,” he says. “Do you see the cascade? All the fingers are still slightly flexed.”

What follows is an animated overview of surface anatomy (bones, tendons, nerves), common pain points (distal radius metaphysis, anatomical snuffbox, hamate hook, dorsal triquetrum), and range of motion diagnostics (pronation/supination, wrist flexion/extension, radial/ulnar deviation, digital motion, the forming of a full fist).

“Be curious little kids,” Woerner says to the class. “You don’t want to miss anything.”

After the lecture, Roper joins members of his team in the operating room to clean infected hardware in a leg. By 9:15 a.m. he’s in the emergency center at the Memorial Hermann Red Duke Trauma Institute rounding on a list of new patients. His typical questions: “Do you smoke? Are you feeling sick? Are you having any problems with your heart? Fevers? Chills?” He often tells his patients: “You’ve been through a lot. We are going to take great care of you.” To babies, he tries to speak softly, soothingly: “Hi, sweetheart. I’m sorry, sweetheart.”

Bone Phone

As a first-year resident and intern, Roper gets some of the most monotonous jobs. Glued to his hip is the so-called “bone phone,” dialed for all ortho-related requests. His days are constantly interrupted by its ring and he often adds names of patients to a list he keeps in the back pocket of his scrubs. The most common ask is for surgery consent—a tedious task but an important one.

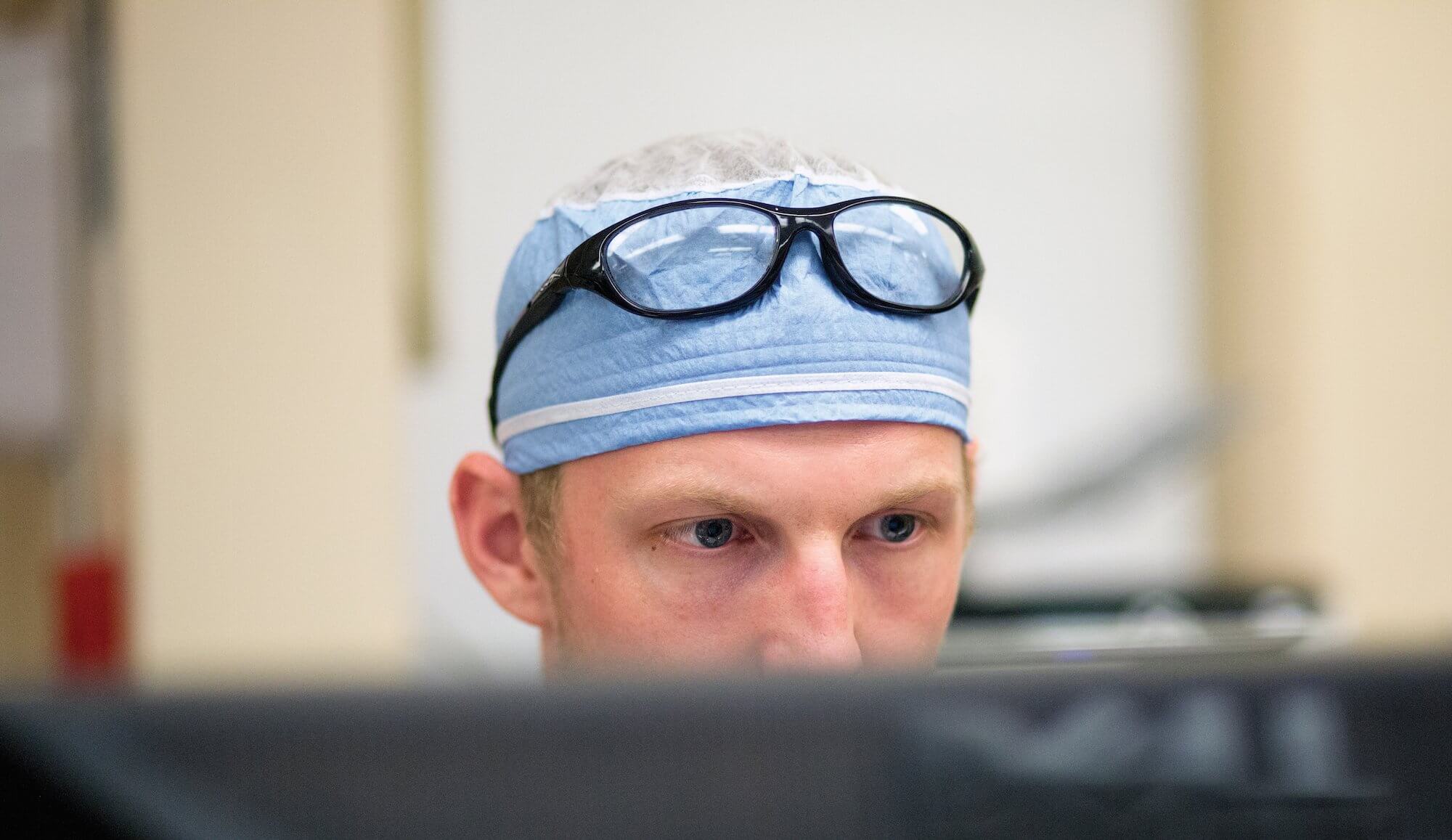

At lunchtime, Roper chooses to skip the cafeteria to input patient notes into the medical records system. He knows the inside of Memorial Hermann as well as he knows the intricate anatomy of a hand. Even though his residency has just started, the campus is familiar: he studied here as part of his curriculum at McGovern Medical School, his top choice after attending The University of Texas at Austin for undergrad.

Roper always enjoyed playing sports and appreciated the intricacies of the human body, but he didn’t always plan on being a doctor. After some trying family medical experiences and surgeries of his own, however, he set his sights on becoming a physician and never looked back. At times he questioned whether he had what it took to really make it to medical school and beyond, but with constant encouragement from professors, he kept pushing.

“I’ve had a lot of great mentors and influences in my life all along the way that have helped guide me and get me to this point,” Roper said. “I wouldn’t be here without them.”

Being Thankful

At 5 p.m., followed by a medical student who has been assigned to shadow him, Roper walks back to the classroom to attend the weekly fracture conference, where residents and faculty eat pizza, present X-rays and ask questions. It lasts until his 7 p.m. team meeting.

Everything is a learning opportunity, a charge to be better.

There is a strict rule that says residents may work no more than 80 hours a week. Even that might seem excessive, but for new doctors, excited about their first jobs, the cap can be frustrating. Roper is 26. When asked about exhaustion and burnout, he says he tries to focus on being thankful instead.

“We’re very lucky to get to do what we do, and sometimes we forget that when we work really long hours,” he explains. “We get to help people and be an important part of their lives. Not everybody gets an opportunity like that.”

After the evening meeting, Roper heads back to the ER to complete a few more patient consults and write a few more patient notes. After a 16-hour workday, his final stop is home, where an anatomy book waits, open, on the kitchen counter.