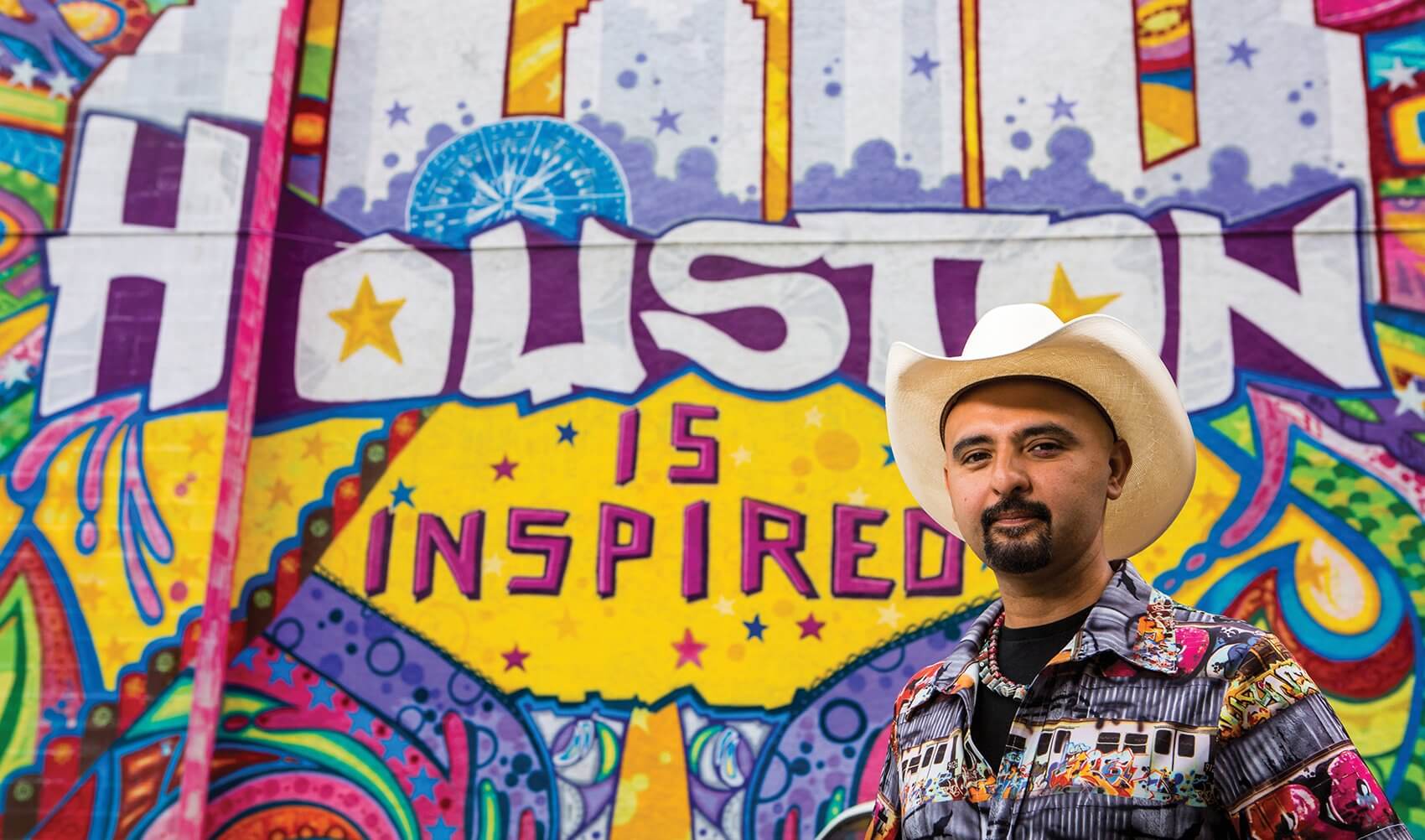

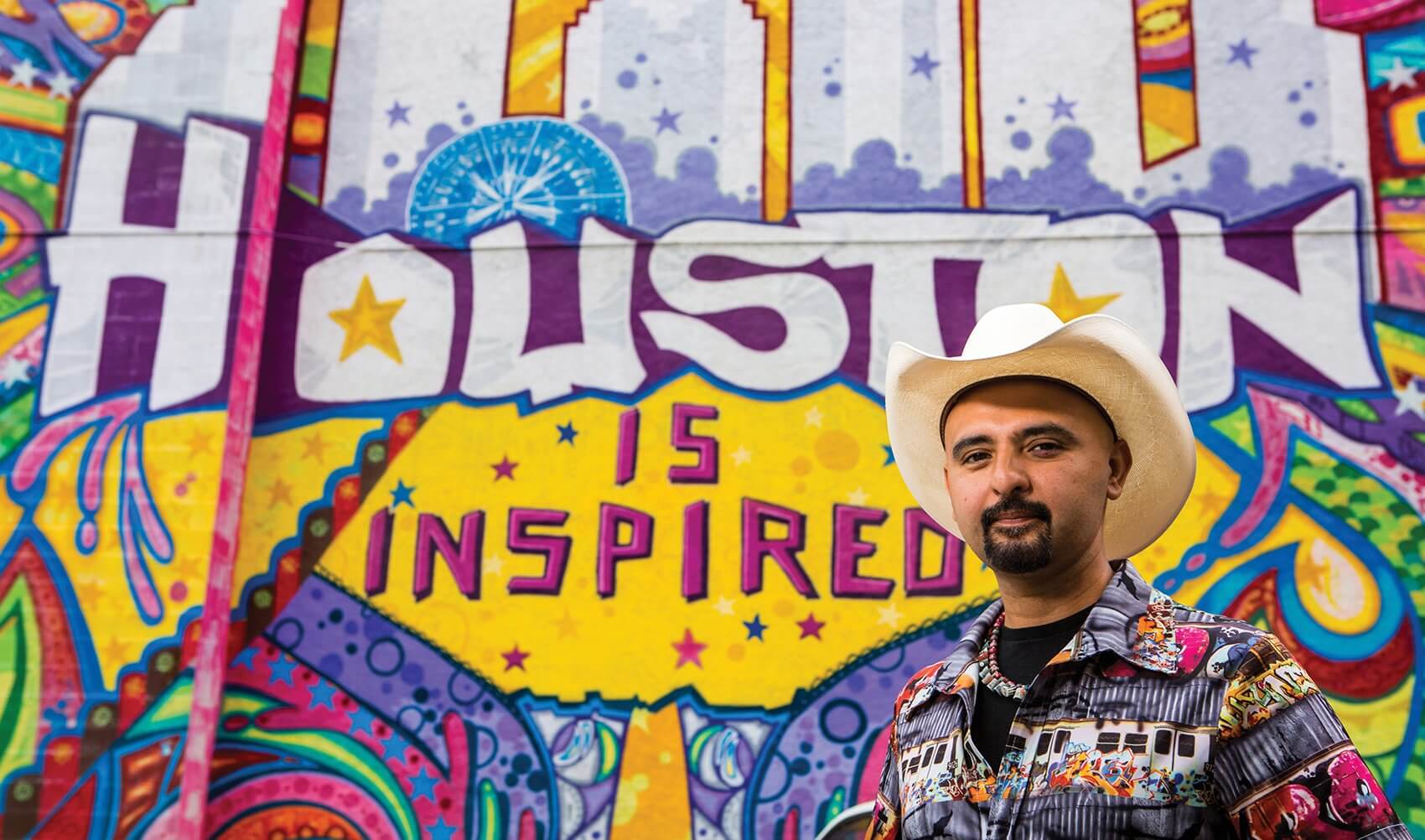

Mario Enrique Figueroa Jr., “Gonzo247”

Houston-born and raised, Mario Enrique Figueroa Jr., “Gonzo247,” artist, founder and chief of operations for Aerosol Warfare, is known for his vibrant murals that capture the spirit of Houston, as well as his creative involvement with promotions for the Houston Zoo, Houston Dynamo and, most recently, the 2016 NCAA Men’s Final Four. He sat down with Texas Medical Center Executive Vice President And Chief Strategy And Operating Officer William F. McKeon to reflect on the history of graffiti art and his own personal journey from an anxious young street artist to a fixture on Houston’s art scene.

Q | Tell us about your formative years.

A | I was born and raised here in Houston and am very proud of it. My parents immigrated here from Mexico. My mom is from a very small farming community, right across the border from Brownsville, Matamoros. It’s like 10 minutes past the border. My dad comes from further south, an area called Michoacán. Both came to the United States. By sheer luck and the power of God, I was born here in Texas. But I tell people, before I claim to be Mexican, before I claim to be American, I claim to be 100 percent Texan. I am very proud of being from this area, and I try to take Houston and Texas anywhere I go.

I grew up here on the east end, Second Ward to be exact, and growing up, we were surrounded by family. Every day we were visiting some other family member. The bulk of my family lived and still lives here in the east end. So it was family, it was church, and always good times. I think I was always artistically inclined. I was always creative, but I didn’t start drawing much until I was a little older—I would say seven, eight, nine. One thing that really affected me, and I think really helped me to see something different, was I had family that lived up on Canal Street. And if you have ever driven up the east end in the last 30 years, there is this mural that was painted by now famous artist Leo Tanguma. At the time, it was the biggest mural in Houston, and I believe it was also the biggest mural in Texas.

The mural was dedicated in ’73, I was born in ’72. So pretty much my entire life I saw this mural while driving up and down Canal Street. At that age, the scale of the work was so incredible to me. I couldn’t fathom how someone could paint that large. The mural was called ‘The Rebirth of our Nationality,’ and it spoke heavily on the Chicano movement of the late ’60s and ’70s in Houston and overall. I didn’t really understand the content, but the images were so powerful, I got a lot of emotion out of it. But that really inspired me.

I thought, ‘Man, it would be great if one day I could create something this big.’ In the mid ’80s, I started listening to what was, at the time, this really underground counterculture music called rap.

Back then, Houston got everything last. So hip-hop in general started filtering into Houston. And for those who don’t know, rap music is one part of the hip-hop culture. So there are four elements in the hip-hop culture: rap is the vocal, DJing is the musical side, break dancing is the dance form of it and the final element is graffiti art. Graffiti is the visual language component of hip-hop. So they are called the four elements, and those four elements are what create hip-hop.

Nowadays, unfortunately, it has gotten so commercial that the only thing that is highlighted when you say ‘hip-hop’ is the music, the rapping. But that’s just one small part of a bigger culture. So that’s kind of how I fell into this, through the music first, and then the break dancing, then the turntables. And this was right at the time when MTV was starting to pop up, and more content was starting to arrive, so through the music I would see the guys on the stage, and in the background was always something really colorful. And that was what started to catch my eye. Once I figured out what it was and who was doing it and how it was done, I was immediately drawn to that genre. I finally found an art form that I connected with. I found an art form that I understood and I found an art form that I felt I could use as a medium or a vehicle to express myself.

Q | Graffiti has had some negative connotations in the public, as well. What is the origin of graffiti, and how did you personally find your way down this path as an artist?

A | Of course, everyone has their own history and everyone has their own version of what happened. But for the most part, a big part of what we consider today to be modern-day graffiti was started in Philadelphia. Most people think it started in New York, but it started in Philadelphia and spilled over to New York. At one point, Philadelphia was considered the graffiti capital of the world. But then it spilled over to New York, and once it got attached to the subway system in New York, that’s when it really just exploded.

And part of the stigma is that graffiti is illegal. For the most part, a lot of it is in the sense that that’s how it started. A bunch of kids were using public mass transit as their rolling billboards to convey their messages. So, being here in Houston, we aren’t East Coast, we aren’t West Coast, we are what we call the ‘third coast.’ And there was no graffiti, or at least nothing that I saw or could reference. Sure, there were the scribbles and miscellaneous writings on the wall, but it wasn’t graffiti as in the modern-day New York style. It was just handwritten stuff. So knowing what I wanted to do, knowing there wasn’t much influence here or anything I could use as a gauge, I realized I had to go research it. And this was back in the mid ’80s, very early ’90s, and there was no Internet. So where does one go for information? And I thought of the library. So I went to the library and I started looking for anything. I wasn’t really sure what I was looking for, but I figured there had to be a book or something written about it.

Nowadays, if you go to the bookstore, there is a whole category just dedicated to graffiti and street art. Well, back then, I wasn’t so lucky. I had to dig using those ancient technologies like the card catalog. So I went through the card catalog looking for graffiti, and there was maybe one card. And the first book I found was about why people write on the bathroom walls. And I kept digging and finally found this card that said, ‘The Faith of Graffiti,’ so I thought that sounded promising. I went and grabbed the book and it was written by Norman Mailer, and at the time I had no clue who he was, but it turns out he is a Pulitzer Prize winner. Very famous. So I read that book, and as weird as it sounds, that was probably the first book that I ever really read, if that makes sense. I felt the book was written about me and for me at the same time. He was one of the first intellectuals to look at graffiti not as in kids who are lunatics and vandals, but he took more of an analytical perspective, and it helped me understand a lot of what was going on.

So reading that book, I near memorized it, and then I started quoting it, and people thought, ‘Man, this is a pretty intellectual dude.’ And I would say, ‘Well, it’s not me, it’s Norman Mailer.’

I’m paraphrasing, but we live in a society where to own property is to have an identity. It’s about what you drive, where you live. So when you have an area like New York back in the day, the younger people back then, you don’t own things, basically you are owned. You don’t have any property. To have the opportunity to be able to grab a can of paint and go to a subway train or climb a billboard and put your name on there, you are essentially letting the world know that you exist. And a lot of this was younger kids just wanting to have a voice, wanting to say that they exist, and wanting to be able to show people that whether you like it or not, I’m here and want to be heard. And that’s kind of where I was at the same time. The difference was, here in Houston, there really wasn’t anyone else doing it.

Of course, yes, in the initial stages of this entire thing, there was that illegal aspect of it. And that’s actually a big drive for the younger generation. The best way I can say it is, until you have done it, it’s really easy to knock kids for doing it. But until you go out there at night with a can in your hand, and navigate through the concrete jungle, find a place to put your name, get in and get out without being caught, it’s hard to describe the adrenaline. It’s very romantic in a sense of a Huckleberry Finn, Tom Sawyer adventure. Very military. You have to do your surveillance, you have to know where you are going to be, what are your exit strategies in case something happens. There is a lot that goes into it. There is a lot of pre-work before you go out and do it. And it’s fun to navigate all of that.

And that’s how I started out doing it. I’m not a hypocrite. I don’t hide my past. I would go out and become this midnight Picasso. But even back then, I did my best to find areas that were already dilapidated, areas that people already gave up on. So for me, my mission was, ‘Why can’t I turn this into something beautiful? It’s already decayed anyway, so why not have some beautiful decay?’ So that was kind of what I was doing.

But then, in 1990, I was graduating from high school and was at that point when you can go in a million different directions. And I didn’t really have a vision yet. I knew that I liked art, and that was about it. I knew I was doing graffiti. So the school that I ended up graduating from brought a motivational speaker to come out and he was high-fiving everyone and telling everyone, ‘You’re going to be somebody.’

So he was talking about all of the things that people do after high school. Some of you guys are going to college, some of you are applying and got accepted. Some of you are going to the military or straight to the workforce. So he gave all of these options as to what people normally do. And I was in the back, thinking, ‘Man, my life must really suck because none of those options appeal to me.’ Toward the end of his speech, he said something to the effect of, ‘Before you go off and do whatever it is you are going to do for the rest of your life, I will ask you one question: What’s the one thing that you love to do so much that you would be willing to do it for free?’ And for me, that was graffiti. I do it for free anyway. And he said, ‘Whatever you are thinking about, you should do that as your career.’

And that just blew my mind. Graffiti as a career? But of course, he is a motivational speaker, so he makes you believe you can do it. So I got really excited. And back then, in 1990, graffiti was still brand new in Houston.

And it was definitely lumped in with gang-related activity, although I was never associated with any gang, but it was just negative—vandalism, mischief. But I had a vision. I wanted to become a full-time graffiti artist. Well, how do you do that? I don’t know. That’s the challenge.

One of the biggest things that I had to do was shed light on what I was doing. And part of that was I had to stepoutfrombehindtheshadows.I realized that people fear the unknown. So as long as everything is in the dark, it is never going to get the light of day. So at that time now, there were other people writing graffiti, and they kind of looked at me like I was crazy, like I was selling out. Why would I come out? I just figured I saw a long-term vision. I wasn’t looking at today, I was looking at 15 years from now, 20 years from now, where are we going to be. So I figured there has to be a face for this—not that I was the official spokesman and represented everyone. But I thought if I could talk to people, shake someone’s hand, communicate what was going on and educate the public, the easier it would be for them to appreciate or even accept. And little by little, that’s what started happening.

I also figured out that if you are going to make money and sell your art, you have to put it in galleries, like put it in museums. There are a lot of options. So, I went to the yellow pages—the old-school Google—and I looked up art galleries or basically anything that said ‘art’ in the phone book. I just went everywhere. I said, ‘Hey, my name is Gonzo, I want to sell my art here.’ And it was funny because pretty much everyone said, ‘You’re a gang member.’ ‘This is vandalism.’ ‘Graffiti isn’t art.’ ‘Get out of here or I’m going to call the cops.’ And I was really taken aback. I thought this was it, this was my ticket.

At the time, it wasn’t considered art. It was slowly making its way through the art community. But I realized, in the ’80s, graffiti was coming off of the subway trains and it was moving above ground onto walls and into galleries, so again, going back to the library, I started digging for more info. I pulled every book off the shelf that was art in America, art news, all of the art publications that they had from 1980 to 1990, because I knew that was when that transition was happening, and something in there had to be something that I could use. I felt like Indiana Jones, digging through the catacombs, and sure enough, flipping through those pages, every now and then I would see an ad for an exhibition featuring ‘Crash’ at this gallery. Perfect. I would write down the information and go home and write letters. ‘Dear so and so. My name is Gonzo. I live in Houston. I saw this ad from a magazine back in the 1980s and I am trying to get information about the artist.’

Writing letters, it was like notes in a bottle. I was just throwing them out there. And this was not email. You put a stamp on it, you put it in the mailbox and you wait. It was a waiting game. And every now and then something would trickle in. But little by little, through that paper pushing and hustling, I started making connections, and through that, I started meeting some of the original, old-school New York subway artists. And I think, at least my impression is, that they probably took a shine to me because I was just this kid from the middle of nowhere interested in what they were doing. So I think that was helpful because we would befriend each other, and develop pen pal relationships, and send photos back and forth of what was happening. So that really also helped show me the vision.

Q | There seems to be a unique naming convention used among graffiti artists. Tell us a bit about that.

A | In the graffiti world, looking more at the historical true nature of the game, the graffiti name is whatever name

you choose to write on the wall and a number associated with it. That’s a true graffiti name. Because back in the day in New York, when the kids were writing graffiti, there would be one guy who was writing Cliff. And then another guy from another part of town, they have never met, he is writing Cliff on the upside of town. And the trains would cross and now there are two Cliffs on a line. Which was which? Did you see my new piece? That one wasn’t mine. And so to distinguish who was who, they figured out a really cool system of adding either the street number you lived on, or the apartment number you lived in. So you can now be Cliff183, because you lived on 183rd Street. Or you could be Cliff62, because you live in apartment 62.

Q | So why Gonzo?

A | I needed an identity. I couldn’t just go out and write my real name on the wall at night. I mean, I could, but why would you? I was trying to find an identity, and a couple things happened. Growing up, people liked to call me Gonzo, and I always thought it was a Muppet.

But one day I ran across the definition of the word. I had no idea it was an actual word, I thought it was just a Muppet. And when I read the definition—unconventional or unrestrained, zany, eccentric, extreme—I immediately connected with the definition. It described who I was, what I was doing, how I was doing it, how I was living life, and I just connected.

So, being from Houston, we don’t really live on numbered streets, and I never grew up in an apartment, so I had to come up with a number to make my name real. So at the time, I thought 24 hours a day, seven days a week. That was how graffiti was part of my life— constant. And I stuck with Gonzo247, and then, I want to say mid to late ’90s, I was watching TV and there was a commercial about Walmart being open 24/7. Any time something gets to the Walmart level, it’s dead. So I was like, ‘I can’t be 247. That’s just not cool. That’s not what I want to be anymore.’ So I dropped the numbers for a while, and I was just Gonzo. But to be honest, I missed that component of my name. It was like a half name. So I thought about it and really liked the numbers, so I brought them back, but say Gonzo 2-4-7, not 24/7.

So I like the traditional aspect of keeping the name and number. Nowadays though, it has gotten crazy. It’s to the point where if you write the same name as someone else, there’s trouble. There is no sharing of the name anymore. I think, fortunately, it’s almost like trying to get a Twitter handle or email address, if you are old enough to be in on the start of it. Now all of the good names are taken. So I was fortunate that I latched on to Gonzo.

Q | Is there a piece here in Houston you are most recognized for?

A | I think the most notable today is in Market Square. And that was a great project. It was, I guess you could say, an experiment. Houston First contacted me with this idea. Long story short, I was part of a photo campaign to advertise Houston as a cool place to be. They were doing a spread of creatives in Houston and had curators, art directors and artists, and I was fortunate to be included in this photograph to represent the street art community, to show that Houston is in touch with that.

So through that, I was asked to create a piece of artwork that they could include in the media packet. I painted a canvas that was probably three or four feet, and we did a high-resolution scan and they used that image, and it was great. And they ended up liking that image so much, they said, ‘Wow, this is cool. Can you reproduce this on a larger level?’ And I said yes. And they said, ‘How big can you go?’ And I said, ‘How big of a wall can we get?’ So we were scouting locations, and it just so happened that Treebeards downtown used to have a mural on the side of the building that depicted Market Square. It was more traditional, had fruits and vegetables, and it was a beautiful mural, but unfortunately the wall had structural damage, so they essentially had to take that wall down and rebuild it. So they had just rebuilt that entire wall, and now where there used to be color was just cinder block. And they found out about this idea and said, ‘Well, we have a wall here. We used to have a mural up and we would like to get something new.’ So it was decided to do that.

When the word got out that a graffiti mural was being put up, there was some pushback, like this was going to ruin the neighborhood. There were some doubters. There was pressure on me to create something that was who I am, but I also didn’t want to offend or scare anyone off. So the piece was created and very fortunately, the response has been overwhelmingly positive, to the point where this has become a landmark and an icon for the city. And I really don’t think any of us thought it would go that far. To the point where I want to say that two years ago, Instagram put out this report and this was the number one image that was tagged or posted for Houston that year, to give you an idea of how big that mural became.

Q | How much has the eld evolved to allow for a demand for the commissioning of street graffiti?

A | I’ve been very fortunate, or probably too stubborn to give up on this dream. But it has been a journey to get to this point. It definitely wasn’t overnight success. I don’t even like to use the word success. But I am a full-time artist. This is what I do for a living, and I am very appreciative any time anyone wants to work with me. I just recently completed a wall for the Dynamo. They did a really cool unveiling of their new uniform, and asked me if I could paint this giant wall as part of the media release. And I did that in like 12 hours, the side of a building.

It was a challenge. I have a lot of great things in store for 2016. I’m actually currently working on some design work for the NCAA Final Four. I’m designing the actual bracket that will be used for the tournament, among other things. So it’s always exciting. I have done work with a lot of great companies here in the city. And people will ask why I am doing this corporate work, but I feel that companies are people too. And any time they want to work with a local artist or support local arts, how can you deny that they are reaching out? It’s easy to say, ‘Don’t do corporate work. You are going to sell out.’ But at the same time, it’s like what’s the point of having that attitude if they are reaching out to have you create something that is going to broaden their reach and talk to another audience or demographic? I think that’s a perfect vehicle to also share the art form.

But on top of that, I also do private commissioned artwork, where people come in and see what I do and they commission me to do private work. And we just recently founded the first street art museum, which is another vehicle for us to be able to showcase the history, document, preserve the culture, and be able to use that as an educational tool to show people where it came from so they can appreciate where it’s at now.

Q | Any closing thoughts?

A | I applaud the work that the medical center is doing. It is such a big part of my life in the sense that the medical center took care of my mom when she had leukemia. The medical center just recently took care of my father-in-law who has Parkinson’s. The medical center employs my aunts and uncles at all levels, and other family members. And I feel that it is such a big part of the city. It is obviously its own city within the city, but I enjoy the fact that when I drive through the city, I can see downtown, I can see the medical center, and be proud of what we have here.