More Than a Biomarker

According to the American Cancer Society, approximately 48,960 people in the United States will be diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in 2015; 40,560 of those individuals are expected to die from the disease. This devastatingly low survival rate—as little as one percent for most Stage IV diagnoses—is partly attributed to the fact that pancreatic cancer is seldom detected in its early stages. All this may change, however, thanks to tiny, virus- sized particles called GPC1+ crExos.

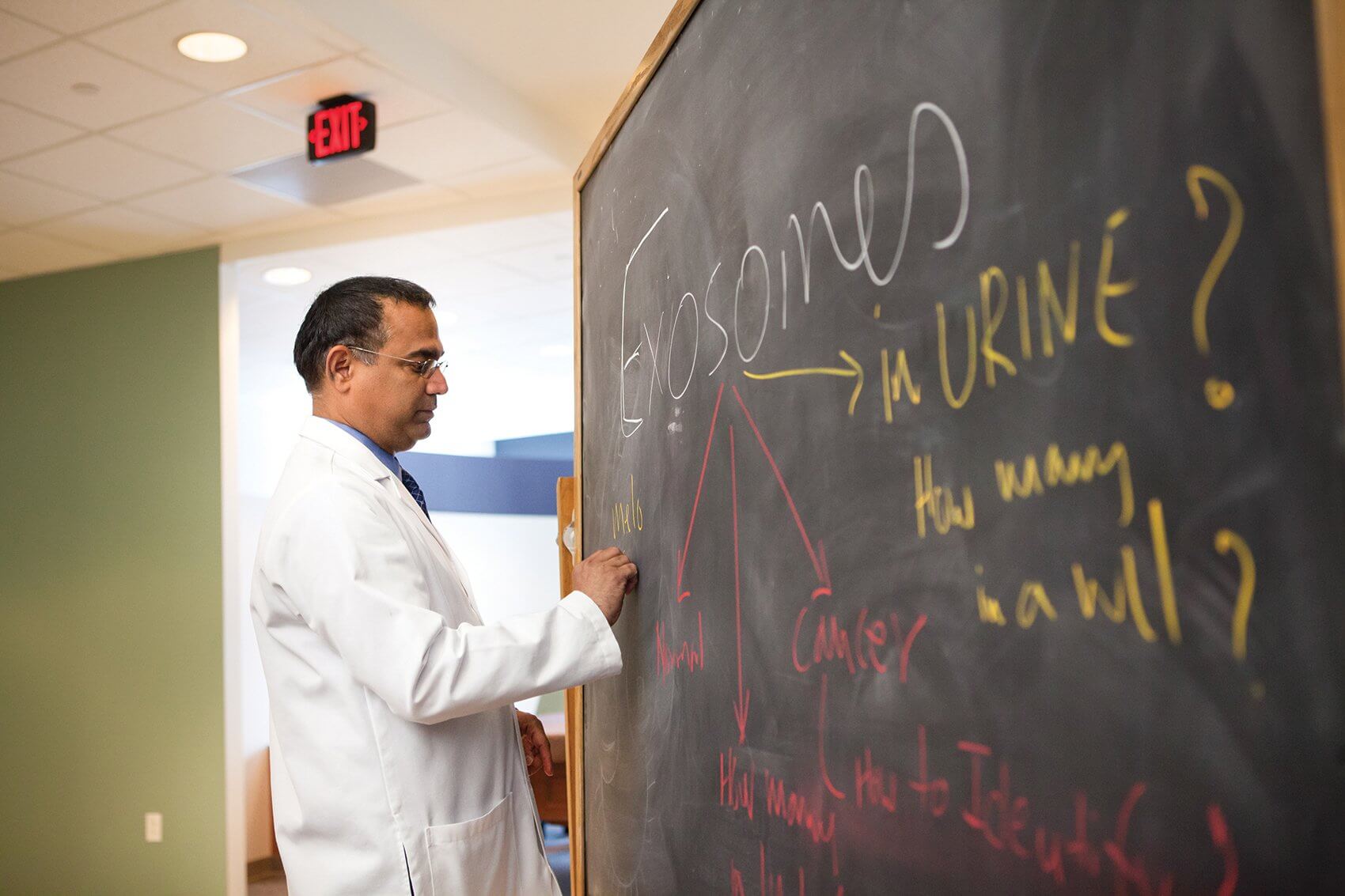

Discovered in the blood of patients with pancreatic cancer cells by researchers at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center and collaborators in Spain and Germany, the presence of these particles, known as exosomes, could be used as a non-invasive screening tool to diagnose early stages of the disease—and as with any cancer, earlier detection corresponds with increased survival.

Published in the June 24, 2015, issue of the journal Nature, the study tested the blood of 251 patients with pancreatic cancer and found evidence of these cancer exosomes in each and every sample. GPC1+ crExos were not detected in the blood of patients who did not have cancer.

“So far, our study shows that with 100 percent sensitivity and specificity, we can detect all pancreatic cancer patients as having these exosomes,” said Raghu Kalluri, M.D., Ph.D., chair of cancer biology at MD Anderson and lead researcher for the study. “Whether that number remains the same when we test 5,000 patients, we don’t know. With any such discovery, you need more validation and proof from various other sources, but this is by far the best we’ve seen compared to any other biomarker available today.”

Because these exosomes are present in large numbers in the blood of patients with pancreatic cancer, the hope is that ultimately, a simple blood test could diagnose the disease. This could have far-reaching implications for screening, diagnostics and treatment, considering there is nothing like it in the field today.

Currently, pancreatic cancer is not generally diagnosed early because symptoms are all but absent until the disease has progressed to a late stage. By the time a patient presents with abdominal pain, weight loss, jaundice, nausea or enlarged lymph nodes, the cancer is almost always too advanced for surgical treatment, which offers the greatest chance of survival by far.

Routine screening for the disease, even for patients with high risk factors such as family history, is prohibitively expensive and can result in false positives—and, because detection relies on imaging such as MRIs and CT scans, still may not spot the cancer in its early stages. A blood test, however, which could measure even the slightest presence of these cancer exosomes, could be offered to the general public, and, based on the results of this study, would provide a definitive—and most importantly, early—diagnosis.

“The hope is that if we can create a tool for early detection, patients will have the opportunity to get surgical intervention for these pancreatic tumors and survival rates will go up,” said Kalluri.

In addition to offering a revolutionary method for exposing the disease at its earliest stages, GPC1+ crExos testing could also be utilized as a monitoring tool for patients already undergoing treatment for pancreatic tumors.

“We could use the test to tailor chemotherapy—to show how well chemotherapy is working or not working, or in the context of relapse or remission or therapy resistance,” said Kalluri. “Based on the levels of the exosomes we see in the blood, we could get an idea of what the tumor burden is in a particular individual, then customize treatment.”

It is important to mention that the most notable pancreatic tumor marker currently recognized in clinical practice, carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA 19-9), is already being used to monitor the progression of pancreatic tumors. Unfortunately, the American Society of Clinical Oncology discourages the use of this antibody for screening purposes due to high incidences of false readings.

Although more research needs to be completed through clinical studies, Kalluri and his colleagues are hopeful that GPC1+ crExos may lead to a breakthrough in pancreatic cancer diagnostics. Interestingly, their study also revealed the presence of these exosomes in some breast cancer patients, suggesting further analysis may offer widespread significance in the broader field of cancer research. If these exosomes are, in fact, present in patients with other cancers, disease-specific assays coupled with genetic analysis could lay the groundwork for blood test screening for numerous types of malignancies. Even more, because exosomes contain RNA, DNA and proteins, GPC1+ crExos may provide additional cancer-specific genetic information and potentially lead to new therapies for the disease.

“More work needs to be done, but we are excited about what we’ve seen so far,” Kalluri said. “These exosomes could prove to be life-saving biomarkers for pancreatic cancer, and, depending on what we discover through further analysis, maybe much more.”