Closing the Gap in Fetal Surgery

When Althea Canezaro discovered she was pregnant, she couldn’t wait to add a new member to her family. Unfortunately, her routine 22-week ultrasound revealed something she didn’t anticipate—spina bifida. In 2014, she and her son, Grayson, became part of a pivotal moment in fetal medicine as the first patients at Texas Children’s Fetal Center to undergo a minimally invasive, two-port procedure to repair spina bifida in-utero.

“After the diagnosis, it was like sitting on a roller coaster ride, except you were sitting still and everything else was moving at a fast pace,” Canezaro recalled. “My physicians in Baton Rouge immediately referred me to Texas Children’s Fetal Center.”

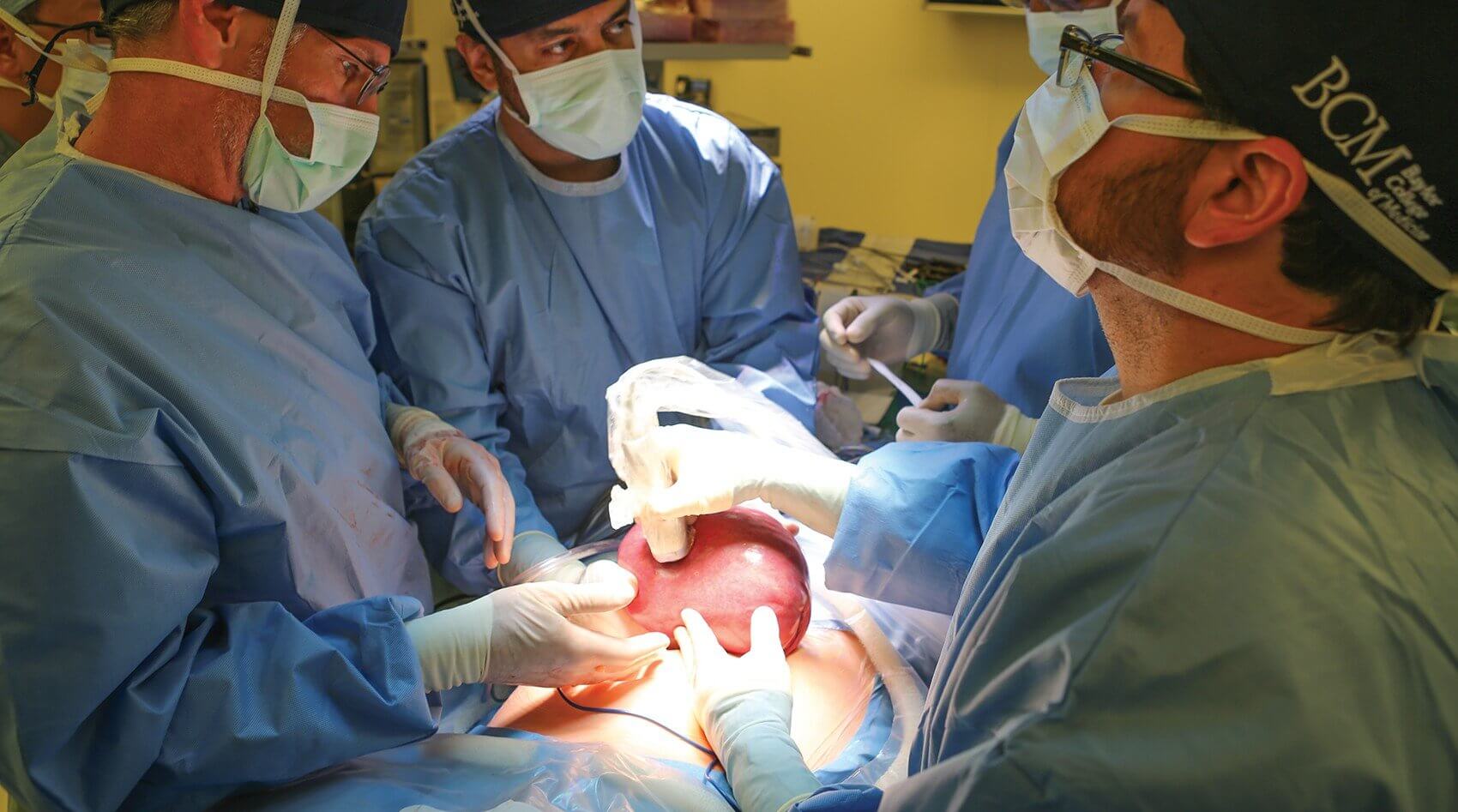

On July 30th, 2014, aided by an expert operating room team and nursing staff, a multidisciplinary team of specialists from Texas Children’s Fetal Center and Baylor College of Medicine performed the in-utero spina bifida fetoscopic closure on Grayson—their first patient. It is believed that this is the first time this type of two-port fetoscopic procedure has been performed in the United States. Prior techniques used a three-port method.

Utilizing an approach developed by Michael Belfort, M.D., Ph.D., obstetrician and gynecologist-in-chief at Texas Children’s Hospital, and William Whitehead, M.D., pediatric neurosurgeon at Texas Children’s Hospital, the surgery was over three years in the making. At 25 weeks gestation, the team successfully closed the opening in Canezaro’s unborn baby’s spine.

“The real innovation here is that we’re doing this repair through two ports with a full neurosurgical closure, using a new kind of repair that Dr. Whitehead has developed with a different suture material from what has been used before,” said Belfort, who is also professor and chairman of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Baylor College of Medicine. “We’re not compromising on the closure of the spinal cord defect, because the only way that this becomes solidified as a success is if the repair is as good as—or better—than an open fetal repair.”

Myelomeningocele, or open neural tube defect (NTD), is a form of spina bifida that occurs in 3.4 out of every 10,000 live births in the U.S. and is the most common permanently disabling birth defect for which there is no known cure. A developmental defect in which the spine is improperly formed and the spinal cord is fused with the skin, myelomeningocele is usually associated with hydrocephalus—a buildup of cerebrospinal fluid in the brain and a leading cause of morbidity in patients.

“Somewhere between 24 and 28 days from conception, an area of the developing spinal cord doesn’t close properly, and the neural tube defect is formed,” said Belfort. “The lesion may have a covering of membrane or be totally open, but either way the nerve tissue is still exposed to the surrounding amniotic fluid. In addition, the defect allows the leakage of the fluid that surrounds the brain causing the lower part of the brain to descend towards the top of the spine. It’s our belief that the exposure of these nerves to the amniotic fluid, compounded by the trauma of them bumping up against the side of the uterus, leads to ongoing damage.”

Previously, closure of the defect occurred either after the birth of the baby or in the first days of life, which had the unfortunate consequence of an 80-90 percent chance that a shunt, a medical device that drains fluid from the brain to the abdomen, would be required and remain for life.

In February of 2003, the National Institutes of Health launched the Management of Myelomeningocele Study (MOMS), a landmark clinical trial in the treatment of spina bifida. Probing the benefits of prenatal surgery, the study demonstrated that a fetal surgical repair leads to lower rates of hydrocephalus, decreases the need for a

cerebrospinal fluid shunt and improves leg function when compared to a standard after-birth repair of the condition. Texas Children’s Fetal Center adopted the technique as a treatment option and began open fetal surgery to treat spina bifida in 2011.

“At the same time, with an open fetal surgery, prematurity is a major risk to the fetus, and in the worst cases, fetal death is a possibility,” said Whitehead, an associate professor

of neurosurgery at Baylor College of Medicine. “Our technique may lower the rate of prematurity—by implementing the two-port procedure, the babies may have a longer gestational age before they’re born, which would be an extraordinary benefit.”

The current open fetal surgery technique involves a uterine incision to accommodate the repair, which has the potential to cause significant maternal complications. The risks of preterm delivery, the necessity of a cesarean section in that pregnancy and all subsequent pregnancies, and the risks of uterine rupture all loom large. In an effort to build upon the success of the MOMS trial, with a focus on reducing the risks to the mother, the team at Texas Children’s Hospital sought an alternative path. Their journey would entail years of preparation and training, both domestically and internationally.

Across the Atlantic, Jose Luis Peiro, M.D., and Elena Carreras, M.D., of Vall D’Hebron Hospital in Barcelona, Spain, had been working on a technique to repair spina bifida in fetal sheep, an initiative that Texas Children’s Hospital supported from the beginning. Working together, the teams at Texas Children’s Fetal Center and Vall D’Hebron Hospital ultimately developed a new way to perform this fetoscopic surgery. A small telescope that can be combined with tiny instruments to allow surgery inside the uterus, a fetoscope would eliminate the need for the 5-6 centimeter opening required for an open procedure.

Designed to counter the risks associated with an open procedure, such as preterm delivery and poor healing of the uterine scar, the new, experimental technique may permit the fetus to be born vaginally, rather than with the cesarean section required for all other babies with spina bifida.

“Our methodology is different,” explained Belfort. “We open the maternal abdomen and exteriorize the uterus—the mother still gets a scar on her belly, but we don’t make the 5-6 cm opening that is required in her uterus for an open procedure. What we’re trying to do is convert a reasonably morbid open procedure into one where the mother’s life is less at risk and her fertility and future pregnancy history are less impacted.”

Refining their technique, the two surgeons performed more than 30 simulated procedures, including two full simulations, gowned and gloved, under actual operating room conditions with a full support team.

“Myelomeningocele repair is a routine part of a pediatric neurosurgeon’s practice,” said Whitehead, “but I’m not used to taking care of fetal patients—we definitely need each other.”

“Incorporating a coordinated approach is absolutely critical when you only have two ports to work through,” added Belfort. “A lot of these other groups have had one person trying to do everything by themselves, but in this technique we work together—I hold the scope and a grasper and Dr. Whitehead performs the suturing and repair procedure. Our instruments have to work together and not impede each other, and given that it involves two people doing one task, it’s not something that’s inherently intuitive. This is an area where nobody has specific expertise, and we’re teaching and training each other while simultaneously developing a new field.”

Belfort affirmed that while the results of their initial cases have been very encouraging, this procedure is still an experimental operation. “We only offer this less-invasive option to patients who have already made the decision to have open fetal surgery because we can always opt for that if needed,” he clarified. “The Texas Children’s Fetal Center is one of the few centers in the United States that performs the open procedure, and the only one to offer both open and fetoscopic approaches.

“We’d love to prove that this technique is the way to go and ultimately end up refining the process further,” concluded Belfort. “If this works, it would be a huge win for women and their babies. With ever advancing technology and imaging capabilities, as well as the work of dedicated surgeons, I am excited to see what the future holds when it comes to repairing anomalies fetoscopically.”

Thankfully, they can already add one win to the charts—Grayson is progressing well after a successful birth on September 21, 2014. “He has not developed hydrocephalus and has full movement of his legs,” said Canezaro. “We are grateful to Dr. Belfort and his team for helping our son achieve this milestone, which would not have been possible without the exceptional care we received at Texas Children’s Hospital and Baylor College of Medicine.”