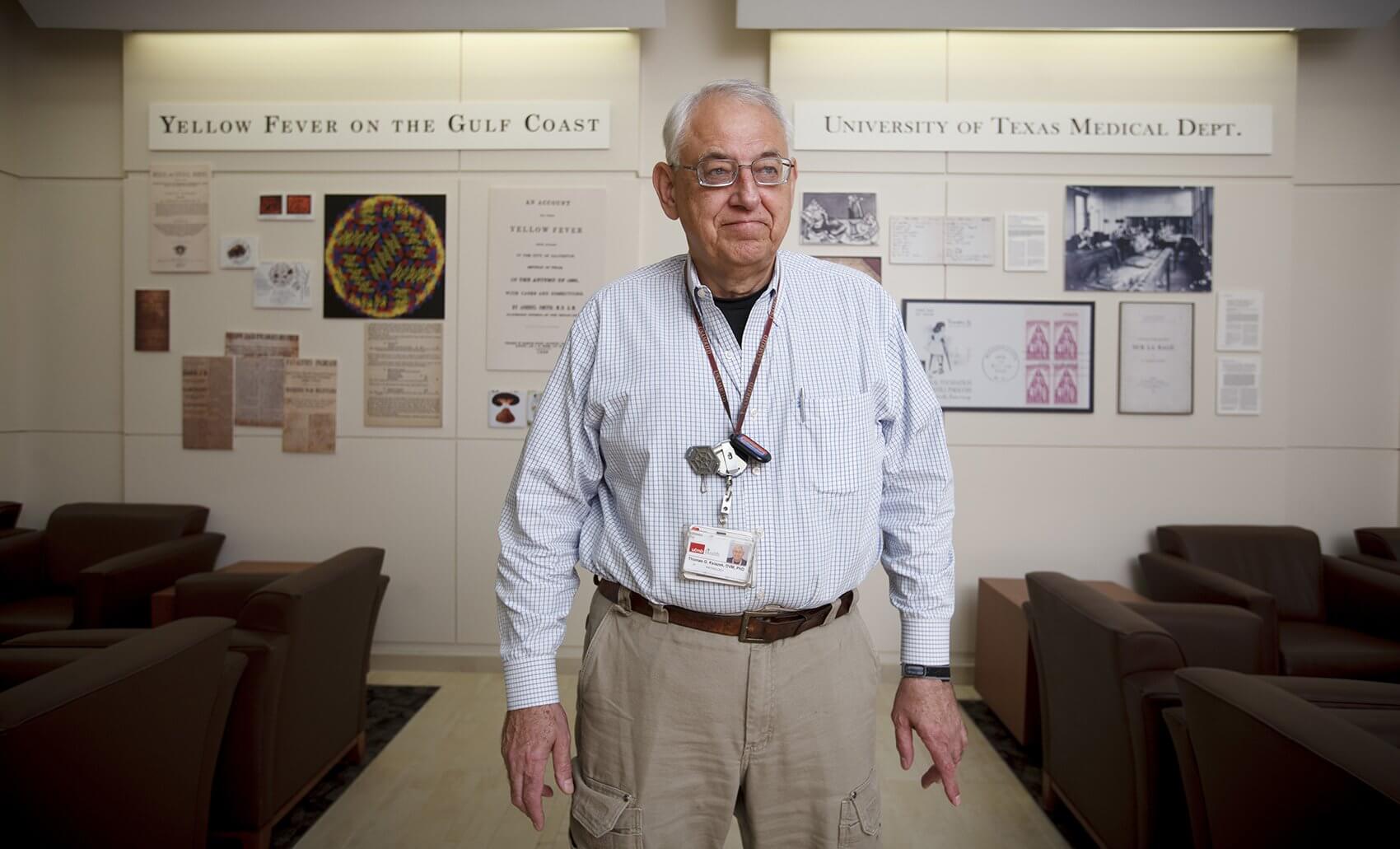

Thomas Ksiazek, DVM, Ph.D.

Even before the first patient in the United States was diagnosed with the virus, teams of health care professionals and researchers were working with officials from West African countries hit hardest by the Ebola outbreak. Thomas Ksiazek, DVM, Ph.D., director of high containment laboratory operations at the Galveston National Laboratory at The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, discusses his life’s work with special pathogens, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention request that took him to Sierra Leone during the largest Ebola epidemic in history.

Q | Can you tell us about your formative years?

A | I graduated from veterinary school in 1970, during the later stages of the Vietnam War, which had the highest troop concentrations. At this time, there was a draft and most of the guys in my class voluntarily enlisted because you might end up going involuntarily. I opted to enter the Air Force under a program called the Early Commissioning Program, which offered some pretty reasonable educational opportunities. They sent me back to university to get a master’s degree. I then worked in a couple of Navy labs in Southeast Asia in the mid 1970s, after which they sent me back to school to get a doctoral degree in epidemiology. This path ultimately formed my career.

What likely had an even more profound effect on my career was that they did away with the Air Force Veterinary Corps while I was in graduate school, so I transferred to the Army’s Veterinary Corps. I ended up in Fort Detrick, Maryland, at the Army’s Infectious Disease Biodefense Institute. It was during my time at Fort Detrick that I got involved with hemorrhagic fevers. I was already working with arthropod-borne viruses but tilted more towards hemorrhagic fevers, like Ebola.

One significant event that happened in the later part of my tenure there was the Ebola episode in the Washington, D.C., suburb of Reston, Virginia. This was the incident that led to the book, “The Hot Zone.” A bunch of monkeys were imported into a facility in Reston. These monkeys were infected with a previously unknown species of Ebola virus that is called now the Ebola Reston virus. I was directly involved in this situation, as I was the head of rapid diagnostics at the United States Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases. Dr. C.J. Peters, who later also came to UTMB, walked into my office late one afternoon and said, ‘Do we have a diagnostic test yet for Ebola?’ and I said, ‘No.’ The virus was sort of partitioned out and only certain individuals worked on it, but I commented that we could put a test together pretty quickly. So, in a matter of a few days we put together an assay for diagnosing Ebola infection by looking for the antigen of the virus. That assay turned out to be quite useful for a number of things, including human diagnostics for Ebola. For a number of years, it was the standard rapid diagnostic test that was used.

So that’s basically the pathway that led me to where I am now. By 1991, I had spent the past 20 years in the armed forces. At this point, Dr. Peters and I went to into public health service work with the CDC. I then spent about 18 years working with them, and eventually succeeded Dr. Peters as the chief of the Special Pathogens Branch.

Q | It sounds like the work you did during your time with the CDC is still relevant today. Has much changed in terms of the concerns the CDC faced then versus those they face now?

A | Well, first of all, the CDC branch that Dr. Peters became the chief of and that I worked with for 18 years was created to deal with special pathogens like the Ebola and Marburg viruses. It was put there as part of the global concern for these types of viruses and the potential for them to play a role in our own nation’s health. The United States Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases was doing some of the same work, sort of from a biodefense angle, whereas the CDC’s chief mission is public health. So, the importation concern was not necessarily because someone was disposed to do harm to the United States, but rather the potential for natural circumstances of outbreaks occurring, like what’s just happened in Dallas. You may recall that the Peace Corps was created in the 1970s.

This was just one of the circumstances that led to imported cases of these sorts of diseases. People living in epidemic areas and then traveling back…if you think about global transport, the revolution of jet air travel transformed how rapidly one can move around the world. In the 1950s, we were still more or less bound by shipborne transport. There certainly were airplanes, but it wasn’t that common to take an international trip. So, for instance, people who were assigned to overseas laboratories—as I was—would travel there. But, essentially, if you wanted to correspond with somebody, you did it by putting a stamp on a letter and sending it. The only time, for instance, that I called home when I was stationed in Indonesia was when my daughter was born. The remainder of the time I merely wrote letters, maybe once a week, to my family and other people that I knew. Nowadays, things are different.

The jet age increased the ability of these viruses to be imported—things like Lassa fever, which is one of the diseases that the Special Pathogens Branch focused on in the 1970s. Later, there was the advent of some of the newer viruses like Ebola in 1976. The CDC designated all of these viruses as BSL-4 agents that must be handled in specially outfitted BSL-4 laboratories where these pathogens could be safely handled, just about the time that I arrived. In the United States, these types of laboratories were really only built and maintained in a couple of places during that era. One such place was Fort Detrick, where the military had a biodefense establishment. The other was a civilian public health establishment in the CDC in Atlanta. In 1989, they opened a brand new laboratory, which was just beginning to be used when Dr. Peters and I came on the scene in 1991.

Q | What brought you to UTMB?

A | I retired from the civil service when I reached my 62nd birthday, per the current civil service retirement system. You become fully vested at 62 and can retire without any penalties, so it was an opportunity to take advantage of the new laboratory that had been built here at UTMB.

There was a cadre of people here with similar backgrounds and very high-level reputations. That was attractive. I was also given the opportunity to work with UTMB’s World Reference Center of Emerging and Arthropod-borne Diseases. This is a rare and expansive source of the types of viruses that many pathogen researchers, including myself, had worked on. That reference center itself is perhaps one of a number of reasons as to why people were drawn here at that time.

At the time that I joined UTMB, the Galveston National Lab had just been built. You may recall that Ike hit in September of 2008. I actually signed my contract to come here the day Ike hit. To give UTMB credit, they offered me the chance to back out of the contract. This lab was not affected by the storm and there was no doubt in my mind it would offer a lot of opportunities for me, so I decided to come. The difficultly was that much of the logistical support for the remainder of campus was damaged so it did complicate getting this lab going.

Q | So you work in the BSL-4. What do you do specifically?

A | I do a few things. First, I have administrative responsibilities for maintaining operations. Second, I am responsible for maintaining, making available and obtaining new strains of interest for the World Reference Collection for use by interested investigators.

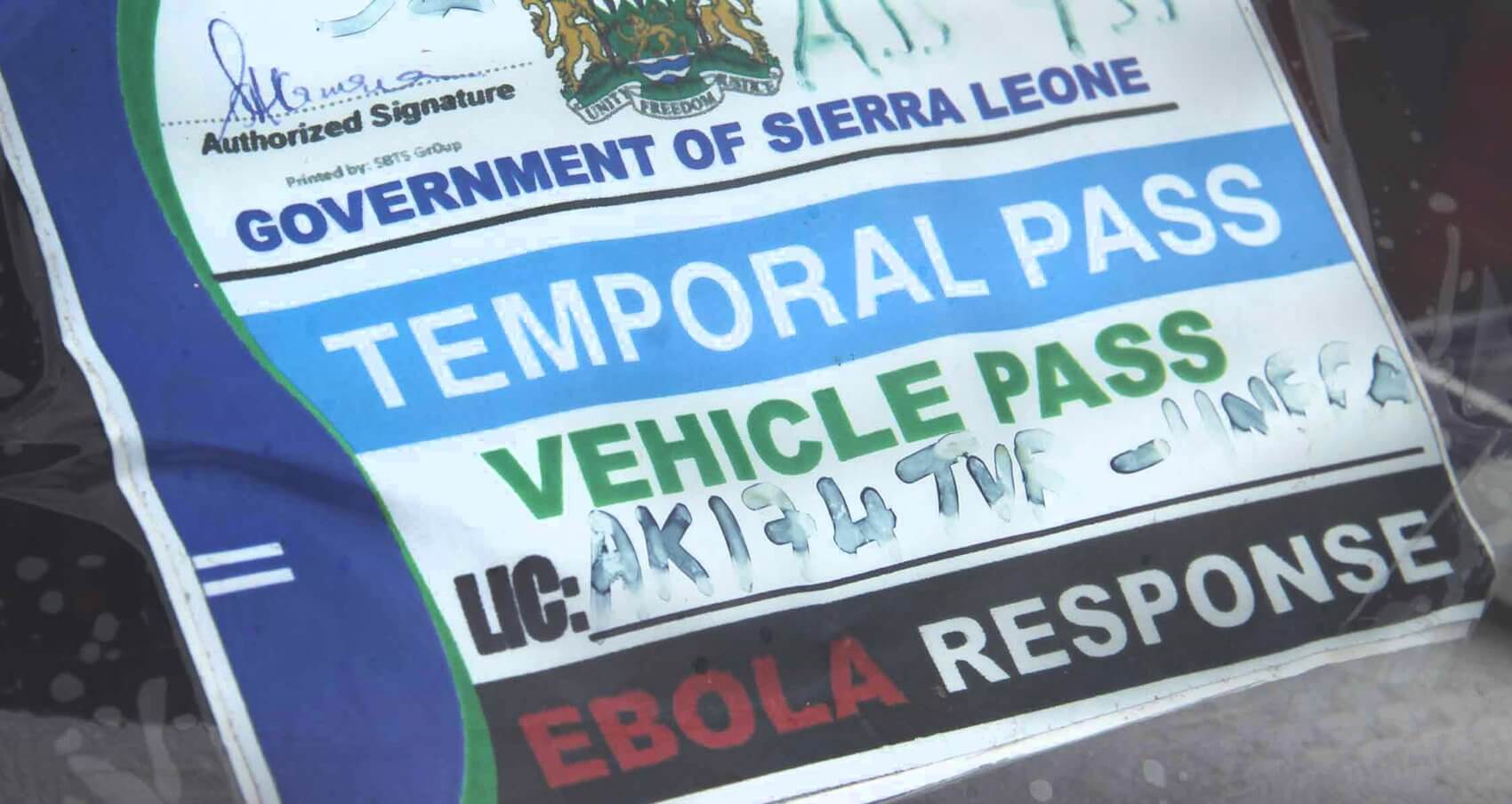

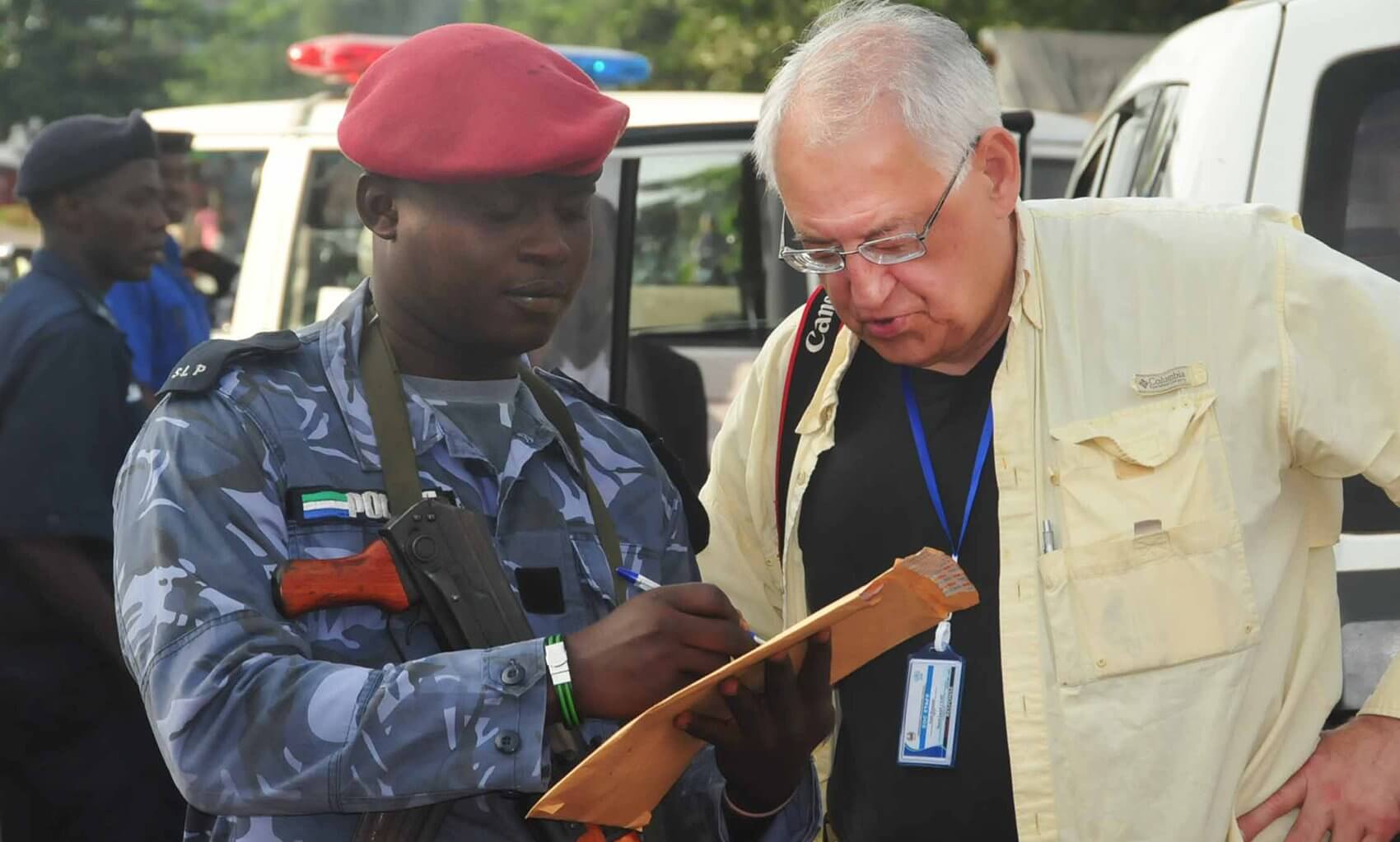

Q | You recently returned from Sierra Leone. Can you tell me a little bit about that trip and what led you to go?

A | I’d say the plain and simple truth of it was I retired from the CDC special pathogens branch, the group that was normally responsible for responding to these operations. The outbreak began this March and the people within the branch had already spent a couple of tours in Guinea responding to that so they were beginning to be somewhat overly in demand. They were looking for other individuals as the CDC decided to expand their efforts into the other two countries of Sierra Leone and Liberia. They had been involved in Guinea for some time and the commitment was to get something like 50 to 75 people out into the field in the affected countries. In order to do that they reached out to me. Dr. Nichol, who succeeded me as branch chief, called me and asked if I would be willing to spend 30 days in Sierra Leone as a CDC team lead. I really had missed being out in the field. It’s harder in a university setting to obtain funding to undertake this sort of response. Since the CDC is the nation’s public health agency, they do that as a matter of course.

Q | So what was your purpose there?

A | My role was to act as a team lead, which is more political than administrative. It was good that I had experience doing this before to provide some gravitas to the response. I spent the majority of my time dealing with national and public health entities and working with the emergency health operations center, a national governing body made up of a fairly large number of international groups like Doctors Without Borders, WHO, World Food Program and a couple of other alphabet-type agencies that generally assist in the developing world in dealing with health, food security and other issues like that. When there are disasters they also respond to those as part of the international community that tries to help affected countries.

Q | For the communities that you visited, what was it that they needed help with the most?

A | Well, there was a variety of things. One of the chief needs is treatment facilities that can help isolate affected individuals. There is sort of an Ebola playbook to find the cases. This is not terribly difficult if you have a small beginning outbreak, then you isolate affected individuals in a facility where they are taken care of by people who are protected from becoming infected themselves. This breaks the chain of transmission. Then you identify those individuals’ contacts so that at the first sign of illness they can be removed from the community. The whole idea behind this is to break the chain of transmission. If you can do that in a thorough manner, particularly if you’re there early, you can stop these outbreaks when they are small. It’s been essentially the means of controlling these outbreaks since the 1995 Kikwit outbreak.

Q | I have heard you mention there are some cultural factors that helped this disease progress as it has. Can you tell us a bit about those factors?

A | There are always issues when you go into an area where literacy rates are low. People may not fully ascribe to the germ theory. When you understand that this is an infectious agent, what I just described in terms of control is fairly easy to comprehend if you get the idea that it’s a germ that is transmitted from one person to another. They may think of it in other terms. One of the big risk factors is that when people die they are still infectious. In funeral practices in some of these areas, it’s common to wash the bodies and fondle them and kiss them. That is a dangerous thing with this particular virus because the virus in patients who become extremely sick and die is essentially uncontrolled. It contaminates the corpse as well as the live patient. So those practices such as ritual washing and handling of the body can carry a great deal of risk. A couple of reports showed these kinds of practices seemed to lead to a large number of people being exposed. Dozens of people can become infected from participating in those funerals. Thus our goals included not only isolating patients but trying to make sure burials are being carried out in a safe manner. In addition, people may die without their community ever realizing they had Ebola. So, you have to somehow introduce the idea that burial practices can be very risky and try somehow to modify community behavior in regard to burials.

Q | I would imagine it really takes collaboration with local leaders in Africa to help educate the community about how this virus is spread.

A | It depends on using community leaders or religious leaders, essentially priests or monks, to convey the message. There also are sometimes black magic or subcultural practices that are not totally visible. Secret societies also can play a role. Traditional healers often work in clinics that practice a sort of standard Western medicine. Sometimes clinics use practices like scarification, cutting with razor blades, that can be quite dangerous in terms of contaminating the individual who is doing it but also when the same instrument is used from one individual to another. Usually if somebody is sick, they go to the healer and he uses an implement. You get a non-sick individual who follows that and the virus is transferred through that process. Those are all things in past outbreaks, including this one, that have played at least some role.

You want to try to keep these things above the surface of society and make people as aware as possible that they are endangering themselves by practicing some of these things.

Q | You have mentioned that you walked the streets of Sierra Leone during your most recent visit, confident in your understanding of how this virus is transmitted.

A | I have done this many times and I’m convinced that this is not an airborne disease. It’s not being transmitted in the way that influenza and other infectious disease are transmitted in an airborne route throughout the community. It really does take close contact with a patient or a deceased individual who had the disease to be at risk. We’ve sent people out to respond to these outbreaks, and in times past we had people who worked with patients. CDC doesn’t work in a clinical fashion with patients any longer, but we do send people into the communities where people are affected. The catchphrase I use is that we’ve always brought back the same number of people that we’ve sent out. This outbreak has been a little different in that generally when CDC people have gone into clinical facilities, infection of health care workers in the supervised environments has stopped. This one is different in that the agencies that usually provide health care in situations like this—Doctors Without Borders for example—have been unable to create enough of their own health care facilities to respond to the scope of the outbreak.

Q | Unlike many of the hardest-hit communities in West Africa, it seems the United States has the resources that are necessary to safely handle and treat Ebola patients. Based on your experiences in Sierra Leone, do you think it really comes down to training and protocol?

A | There are a couple of ways health care workers are probably infected. They get their gloved hands contaminated. Then perhaps they begin to have problems with their goggles. Next, they adjust the eye protection with their gloved hands and introduce the infection to the face. If the health care worker is sweating, the infection runs down the skin. That’s not so much of a breach of a protocol other than health care workers should keep their hands from their faces. In circumstances where you are near equatorial countries that are quite warm and rainy, if you’re wearing PPE that’s essentially impervious to fluids, it gets very hot and you perspire heavily. In fact there’s a great risk of heat stress or heat stroke if you work for periods of time that are excessive. So in general, agencies like Doctors Without Borders insist that they work no longer than two hours, I think. If you go beyond that you’re putting yourself at risk for serious health consequences, not necessarily from Ebola but from heat stress. In a situation where you are sweating profusely and you are wearing eye protection of some sort, it may fog your goggles and then you can’t see.

Or you’re sweating and somehow you have to adjust your goggles. Or the beads of sweat that are coming down around your goggles are creating an issue and you inadvertently contaminate your forehead or some part of your body where that sweat carries the virus. Another very common thing is that when people come out of the facility they somehow contaminate their hands with fluids that have gotten on their garments. And maybe they haven’t cleansed their hands, which touched their garments, and at this point they rub their eyes, nose and mouth. One way to avoid that is to decontaminate the person by spraying them with a fairly strong hypochlorite solution to kill the virus before they take off their garments. This diminishes the possibility of getting it from gloved hands to other parts of the body that can spread around and contaminate mucus membranes.

Q | Any closing thoughts?

A | Myself and Dr. Jim LeDuc, director of the Galveston National Lab, were appointed to the Texas Task Force on Infectious Disease Preparedness and Response on October 6 and, although I cannot speak to the specifics of this task force, in general the idea was to get a group of people together with various kinds of expertise to advise the government of Texas on ways of improving the response to Ebola and what may become the pandemic of a new virus and to be better able to handle this one under present and near future circumstances. UTMB is going to play a big role in not only the current Ebola response, outbreak and possible treatments and vaccines, but in future infectious disease outbreaks and discoveries, and I’m very proud to be a part of the work we’re doing here.