Unraveling the Mysteries of Pregnancy

The biology of pregnancy is entering uncharted waters. Groundbreaking new research demonstrates that the placenta harbors a small, but diverse, community of bacteria capable of influencing the course of pregnancy, reported researchers from Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children’s Hospital, overturning previously held beliefs that it is mostly sterile.

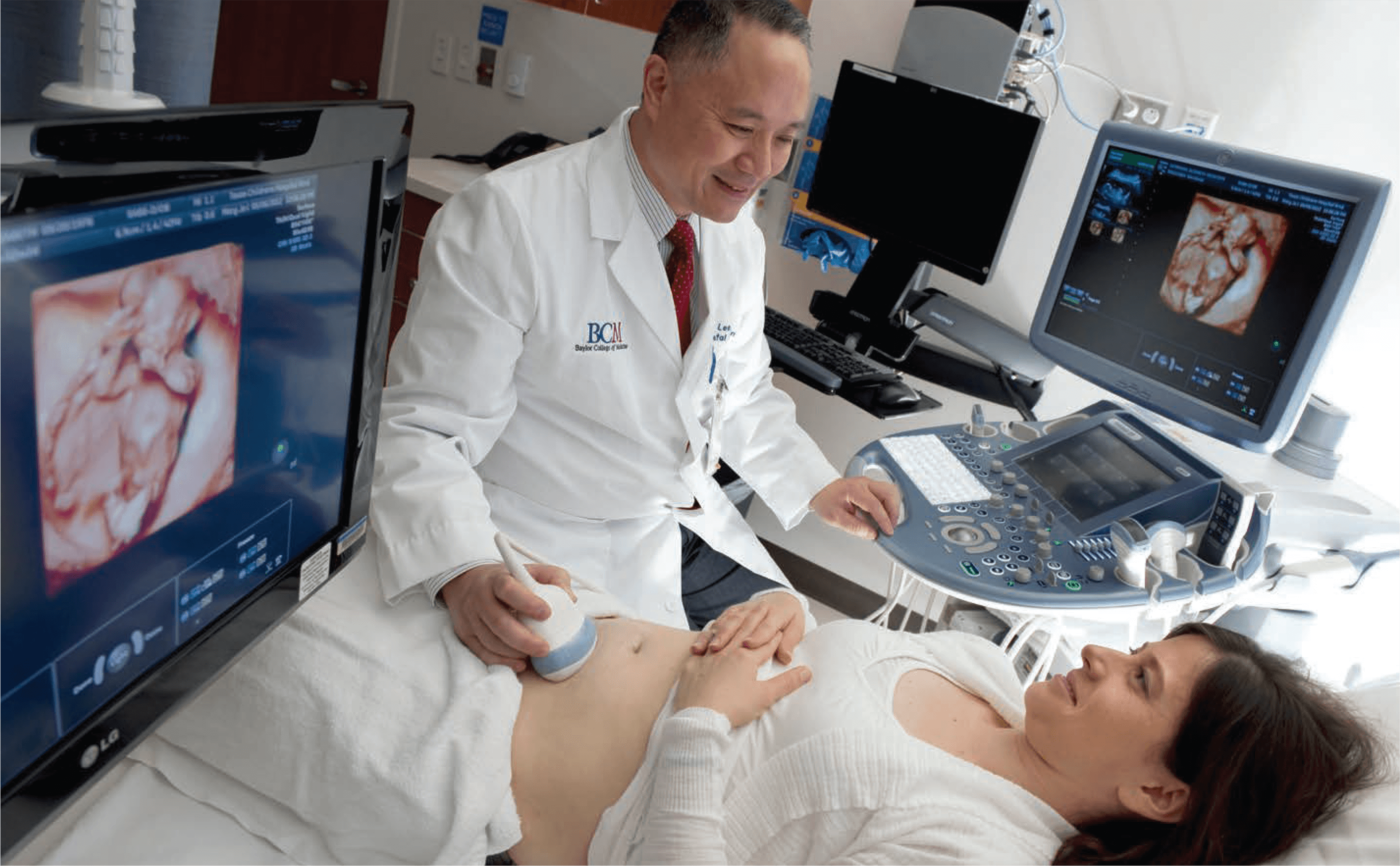

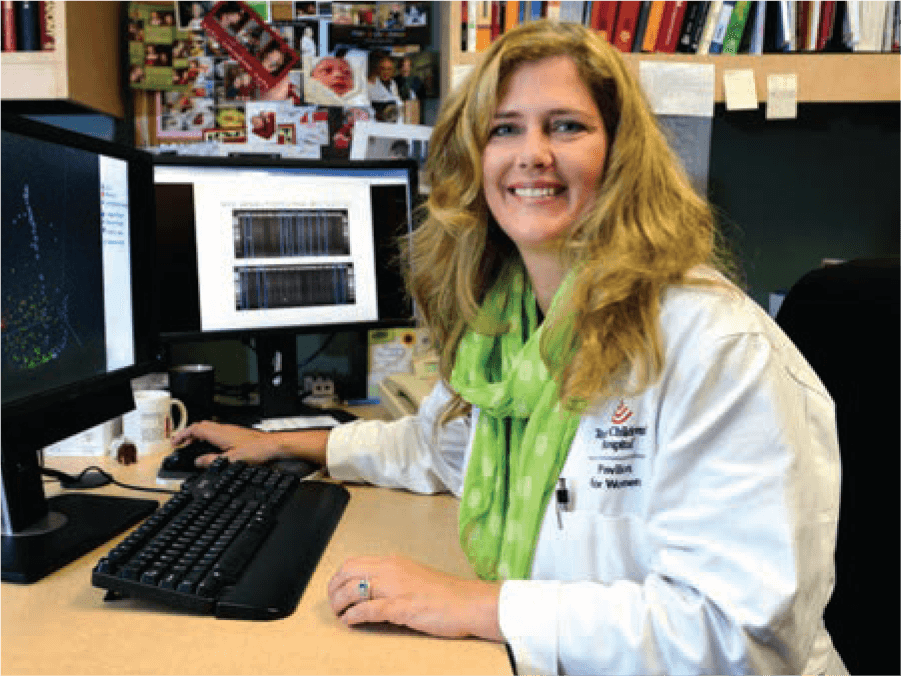

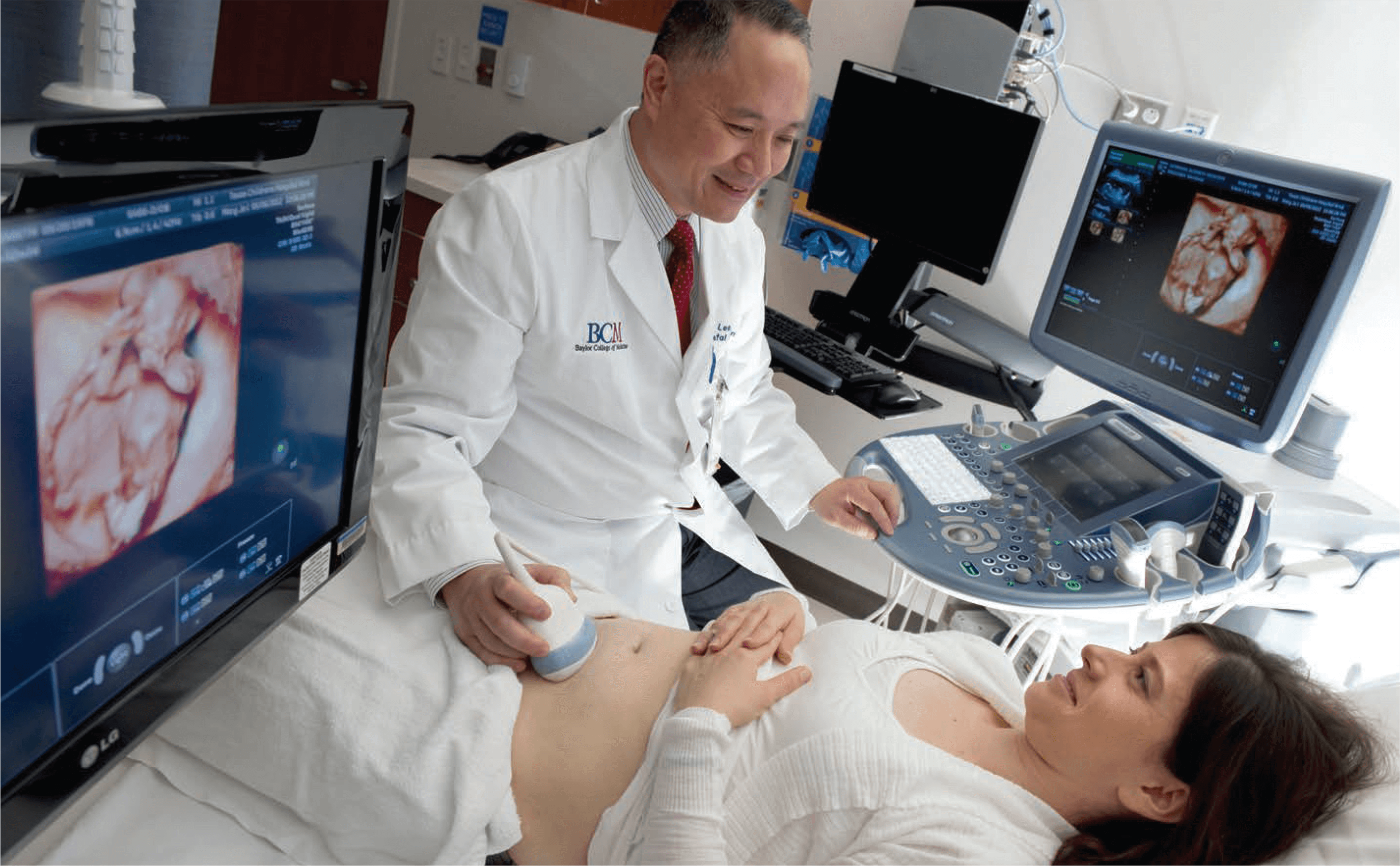

“We’re really just beginning to understand the broader role of the placenta in shaping the overall health of a pregnancy,” said Kjersti Aagaard, M.D., Ph.D., associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology in maternal fetal medicine at Baylor and the Texas Children’s Pavilion for Women, as well as the lead and corresponding author on the report. “As the interface between mother and child, the more that we can understand about what leaves ‘footprints’ on the placenta, the easier it’s going to be to track and appreciate the impact of environmental exposure on pregnancy health and the health of our next generation.”

The findings, published in the most recent issue of Science Translational Medicine, illustrate important new insights on the structure of the placental microbiome, the organisms present, and how they might be capable of impacting a pregnancy. The microbiome refers to the population of microbes—trillions of bacteria, viruses and fungi—that colonize the human body. These organisms influence digestion, metabolism and an array of unknown biological processes. Research to characterize these microbial communities is essential for understanding human development, explained Aagaard.

Aagaard and her colleagues are key members in the collaborative National Institutes of Health (NIH) funded Human Microbiome Project, which seeks to further characterize these communities and how they relate to health and healing human disease.

In this study, the first and largest to focus on the placental microbiome, 320 human subjects’ samples were analyzed comprehensively following a process called shotgun metagenomic sequencing. The technology enables microbiologists to uniquely evaluate bacterial diversity and detect the abundance of specific microbes and all their genetic pathways in a community.

“It started, from my perspective, in really trying to understand the dynamics of the microbiome during pregnancy,” added James Versalovic, M.D., Ph.D., co-author on the report, professor of pathology and immunology at Baylor and head of pathology at Texas Children’s. “In 2011 we initiated the PeriBank at Ben Taub General Hospital, aided by the support of Baylor and Texas Children’s Hospital’s Pavillion for Women, to begin to collect placental tissue from every birth where parental consent was provided. It created an incredibly precious resource for clinical research in obstetrics and gynecology, enabling us to look for bacteria using DNA sequencing.”

In determining that the placenta is not sterile— meaning free from bacteria or other living organisms— the researchers identified that it actually harbors a diverse and unique microbiome. The placental microbiome is relatively low in terms of microbial abundance, explained Aagaard, and modern genomics techniques are required to observe or identify the bacteria present.

Of the samples, Escherichia coli (E. coli), a bacteria that lives in the intestines of most healthy individuals, was the most abundant species. Prevotella tannerae (gingival crevices) and non-pathogenic Neisseria species (mucosal surfaces), both species of the oral cavity, were also detected in highest relative abundance.

“Interestingly, when we looked very thoroughly at the placenta in relation to many other sites of the body, we found that the placental microbiome does not bear many similarities to the microbiomes closest in terms of anatomic location,” said Aagaard. “Specifically, it is not much like the vaginal or intestinal microbiome, but is actually most similar to the oral microbiome.”

This finding has important implications on the likely importance of oral health during pregnancy, she said. “It reinforces long-standing data relating periodontal disease to risk of preterm birth.” Clinically, these results have the potential to prompt an increased emphasis on oral hygiene in pregnant women while simultaneously spurring research focus on the connec- tion between the oral cavity and the placenta.

“We’re very interested in characterizing the connections between microbiomes,” said Versalovic. “Generally, people refer to the human microbiome as if it’s one thing, which it is, but there are still distinct microbial communities. We’re exploring the ways that you can change the microbiome in the oral cavity and have an effect, remotely, at a distal site. We’re examining those connections in other places, as well—for example, by influencing the intestinal microbiome it seems as if there’s an effect on brain function. So, naturally, we’re interested in how the oral cavity and its microbiome may affect pregnancy and preterm birth.”

Additionally, the researchers observed differences in the placental microbiome based on a remote history of infection during the pregnancy—most commonly urinary tract infections from many months ago that were treated successfully with antibiotics.

The researchers have identified another factor that structures the placental microbiome in unique ways: preterm birth. “Within a reasonable margin of error, we’d be able to tell whether someone had a preterm birth by metagenomically characterizing the placental microbiome profile,” said Aagaard. “If we examine the differences between mothers who have had preterm births versus term births, that’s the first step on the way toward meaningful interventions.”

Exposure of the fetus to a placental microbiome may have fundamental implications for early human development and the physiology of pregnancy, added Versalovic. A larger study led by Aagaard and her team is currently underway to expand these findings to describe the placental microbiome profiles across pregnancy and in relation to preterm birth.

“The hope is that we will get a clearer picture of how several of the microbial communities in women and their placentas change over the course of the entire pregnancy among those at risk for preterm birth. These discoveries could lead to rapid breakthroughs in not only identifying women at risk for preterm birth, but developing new and worthwhile strategies for prevention,” said Aagaard. “As we catch glimmers of the microbial biology of pregnancy, we can start to see a not too distant future where we will prevent preterm birth (or its complications in newborns) with truly novel approaches aimed at enhancing the healthy microbes of not just the vagina, but the mouth and gut, as well. By unraveling the mysteries of pregnancy, we are learning that our microbes may be as much friend as foe. This is fantastic news for our moms and their babies.”