Tackling Tropical Diseases

Diseases of poverty.

That’s a more fitting name for neglected tropical diseases, according to Peter Hotez, M.D., Ph.D., founding dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine. They are diseases that contaminate bathing and drinking water, cling to the feet of children playing barefoot in dirty streets, and are carried thousands of miles by ticks and mosquitos. They not only linger in places of poverty, but also seem to cause poverty. And Hotez’s team intends to do something about them.

“Over a billion people in the world suffer from neglected tropical diseases, and about 1.3 billion people live on no money. That includes 1.65 million families in the United States that live on less than two dollars a day,” said Hotez.

“We call them tropical diseases, but it is really a misnomer. They are diseases of poverty. The tropical and subtropical climate is a component of it, but poverty is the overriding determinant.

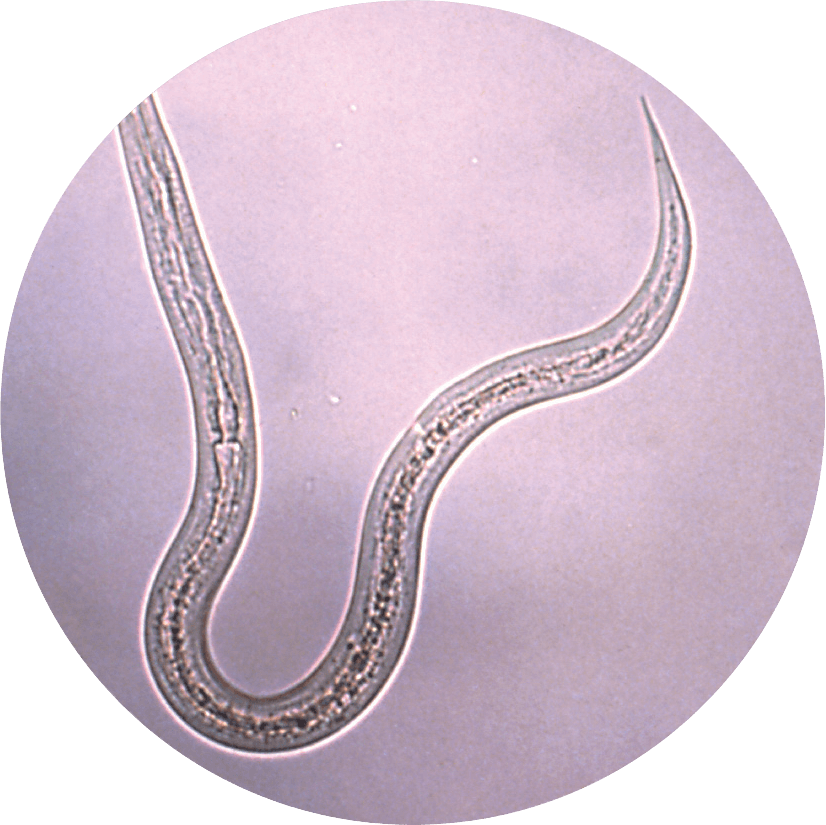

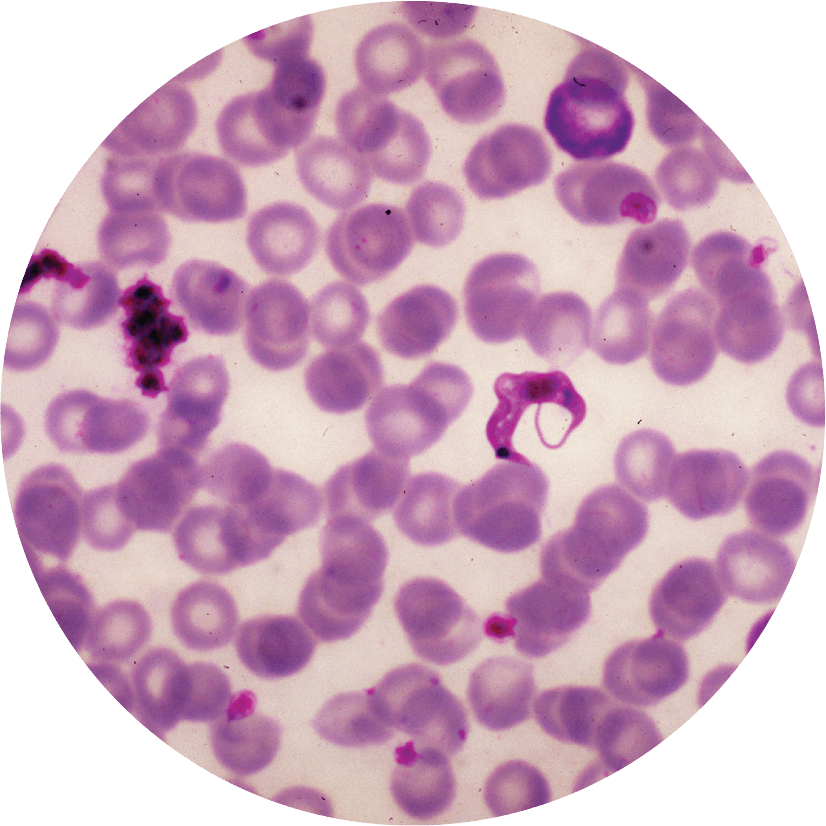

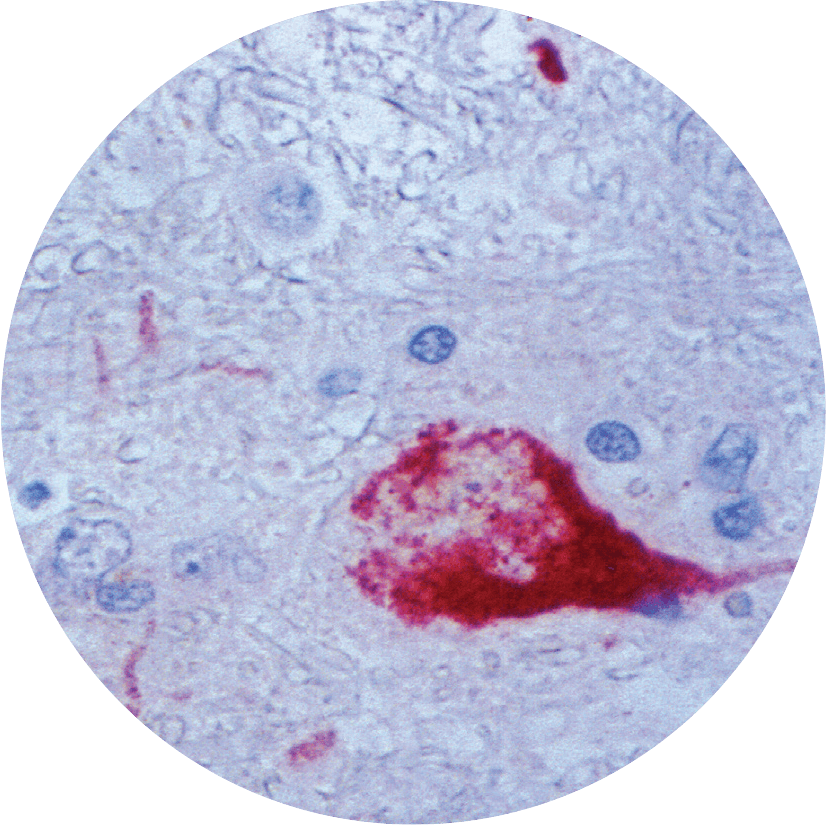

“Many of these tropical infections are not like infections you typically think of. These tend to be chronic, debilitating conditions — things like leprosy, or hookworm, or shistosomiasis,” he continued. “Sometimes people have these diseases their entire lives, making them too disabled to work, so they lose income. Or these diseases actually reduce child intelligence and cognition. They shave IQ points off of kids, so they lose future wage earnings. And this has actually been shown. So these are major forces that actually trap the bottom billion in poverty.”

For years, Hotez and his team have envisioned the Texas Medical Center as being the ideal place for expanding and creating novel strategic collaborative research efforts dedicated to addressing those issues of global health. So when the opportunity arose, following a conversation with Texas Children’s Hospital Physician in-Chief Mark Kline, M.D., and Baylor President Paul Klotman, M.D., for the establishment of a new school dedicated to researching and addressing neglected tropical diseases, Hotez, then the chair of Microbiology, Immunology and Tropical Medicine at George Washington University, didn’t hesitate.

His George Washington University colleague and vice-chair, Maria Elena Bottazzi, Ph.D., was the natural pick to join him as associate dean of the new school. Together, the pair, along with twelve experienced researchers who also relocated to join the team, established the National School of Tropical Medicine.

This endeavor was also made possible by the strategic partnership between Baylor, Texas Children’s Hospital and the Sabin Vaccine Institute, for which Hotez also serves as president. The Sabin Vaccine Institute relocated its Product Development Partnership (PDP), which is one of

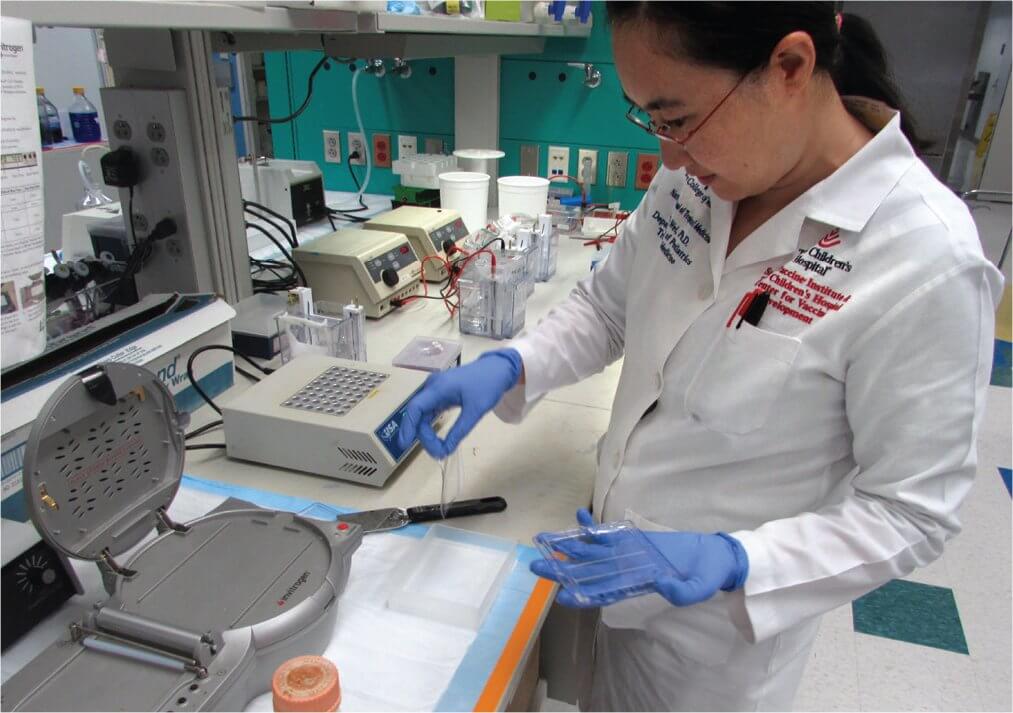

only 16 PDPs globally and the only one located in an academic medical center and in the state of Texas. Hotez and Bottazzi serve as director and deputy director, respectively, for the Sabin PDP. They also serve as professors of pediatrics and molecular virology and microbiology, and Hotez holds the Texas Children’s Hospital endowed chair in tropical pediatrics.

“Dr. Hotez and his team at the Texas Children’s Hospital – Sabin Vaccine Institute Center for Vaccine Development are working to prevent some of the world’s biggest medical scourges, diseases like hookworm and schistosomiasis that literally affect hundreds of millions of individuals globally,” said Kline. “The potential of this absolutely novel work to impact the lives of many of the world’s poorest and least fortunate children cannot be overstated.”

Modeled after the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, the National School of Tropical Medicine has a fourfold mission, centered around research, training, clinical activities and public policy.

While often found in tropical regions, where weather and environment allow disease to spread by way of insects, soil or contaminated waterways, the diseases Hotez and his team work with are not exclusive to any one region or climate.

“People often think of these as sub-Saharan African diseases, but what we are finding is that the world has changed,” said Hotez. “These are not just diseases of Africa, or developing countries. This whole concept of developing versus developed countries, I like to say ‘That’s your father’s global health.’ That’s not the way it is anymore. It’s wherever you have poverty. It doesn’t matter if that poverty is in Southern Mexico, Northern India, Northern Brazil, or the Gulf Coast of Texas. This is where you find tropical diseases.

“We have a particular emphasis on diseases of the poorest regions in the western hemisphere. Not exclusively, though. We do projects in Africa and Asia, but particularly in Latin America,” he added. “It is an important area of emphasis. In fact, the largest number of people living in poverty live in the state of Texas, so we have now found a substantial burden of tropical diseases here in the United States, in the Gulf Coast.”

When addressing treatment and prevention of neglected tropical diseases like Schistosomiasis, caused by parasitic worms that affect 250 million people outside of the United States, it often comes down to doing the work that many pharmaceutical companies will not.

“The vaccines that we are developing are vaccines for the poorest people in the world,” said Hotez. “Industry is not going to make these vaccines because they only affect people of extreme poverty. So it is really science for the poor. We make the vaccines that the drug companies can’t make or won’t make.”

“No one else is making these vaccines because products developed for the poorest populations in the world generally have no commercial return on investment,” added Bottazzi. “So usually those who really can commit to support those populations are either groups in the nonprofit sector, or the governments or the population itself.”

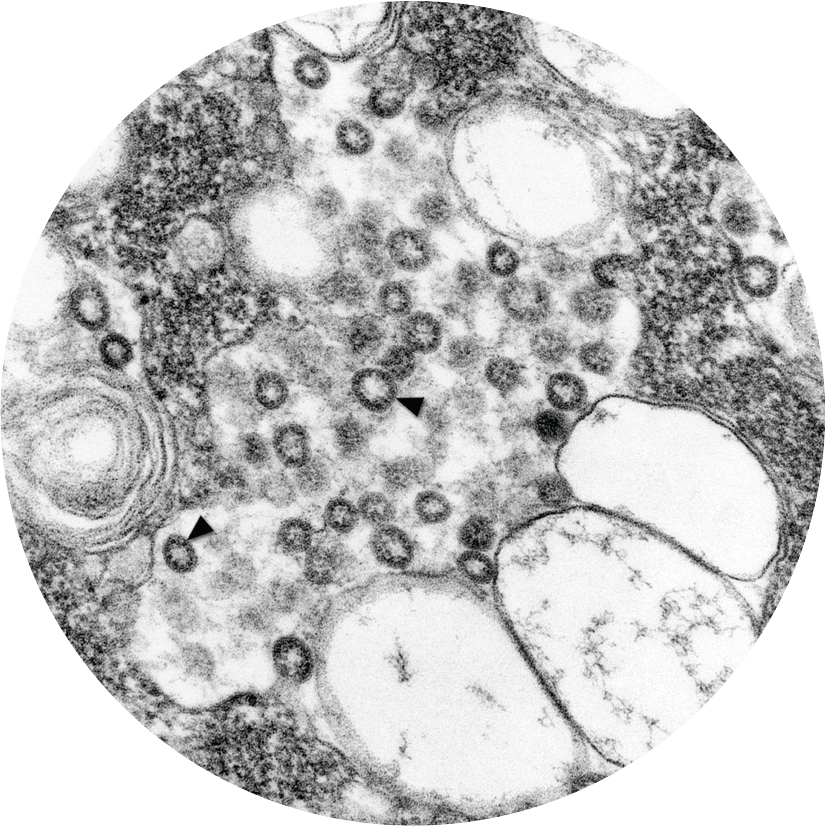

Through the PDP model, the Sabin Vaccine Institute and Texas Children’s Hospital Center for Vaccine Development and the National School of Tropical Medicine are actively working on a number of vaccines for some of the major “diseases of the poor,” including a human hookworm vaccine, now in clinical trials in Brazil and soon in Africa, a shistosomiasis vaccine that is about to start clinical trials, and new vaccines for Chagas disease, Leishmaniasis and Sever Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS).

“A lot of university-based vaccine institutes call themselves vaccine institutes because they do immunology with an interest in vaccines,” said Hotez. “What’s unique about us is we actually make the vaccines, and transition them from discovery, into the clinic. We are doing everything that a small to mid- size biotech company would do, but in the nonprofit arena.”

Beyond developing vaccines, the National School of Tropical Medicine has core faculty working on other major areas of tropical medicine. Major programs in the epidemiology of vector-borne and zoonotic diseases, for example, are headed by Kristy Murray, DVM, Ph.D., an associate professor in the department of pediatrics where she is also associate vice chair for research. Murray’s group has made important discoveries that include the first identification of epidemic dengue fever in Houston, a new renal disease syndrome that results from West Nile Virus Infection, and the transmission of Chagas disease in southeast Texas. In addition, Rojelio Mejia, M.D., and others are leading efforts for the development of new diagnostics for parasitic infections.

In the area of training, the National School of Tropical Medicine provides a unique Diploma in Tropical Medicine for physicians, physician assistants and medical students to recognize and understand how to identify and treat these diseases. Given the ease of international travel, it is critical that physicians have the skills to help isolate or possibly stop the spread of tropical diseases, particularly those transmitted through human contact.

“Part of this arose out of the fact that when the dengue epidemic occurred in Houston, Dr. Murray found that not a single case was diagnosed by physicians,” explained Hotez. “Physicians are not getting trained in most U.S. medical schools about these diseases—how to recognize them, how to diagnose them, and how to manage, treat and prevent them. Because they have always been thought of as problems unrelated to the United States. In fact, we find they are very much related. So we are really trying to expand our collaborations to include a lot of major universities in the area.”

Collaboration and strategic partnerships are crucial to the success of the school. From running the Tropical Medicine Clinic and Travelers Clinic in conjunction with the Harris Health System and Baylor Clinic, to working with international researchers and governments on jointly developing vaccines, the tropical medicine team recognizes the incredible power of partnerships. They take that same approach in tackling issues of health policy. They are, among many other projects, currently working to introduce new legislation to Congress around tropical disease, and the distribution of packages of medicine that have so far reached over 250 million people worldwide.

Hotez and Bottazzi hope to leverage these kinds of allies and resources to help carry their mission even further. “I am so grateful to the vision of Dr. Mark Kline, Baylor College of Medicine President Dr. Paul Klotman, Texas Children’s Hospital Chief Executive Officer Mark Wallace, and Sabin Vaccine Institute Board Chairman Mort Hyman,” said Hotez.

“Our school is at the forefront of global health innovation, and the future looks very promising for tackling tropical diseases,” added Bottazzi. “Together with our strong partnerships within the Texas Medical Center, we will be able to serve as global health accelerators and bring new knowledge, new interventions and renewed access to care to the people in need, locally and around the world.”