A Watchful Eye on the Medical Center

Tropical Storm Allison made landfall on June 5, 2001, dropping over 15 inches of rain in three hours in the city of Houston and earning the distinction of one of the most intense rainfalls to ever hit an urban area in the United States. Severe storms and hurricanes— including Ike and Rita—have hit the region since, but none have impacted the Texas Medical Center as severely as Allison.

The most damage from Allison came from flooding in the tunnels and basements connecting several member institutions, although others were also hit with costly infrastructure damage and loss of invaluable research equipment, animals and samples. Baylor College of Medicine alone lost 60,000 tumor samples, collected over decades.

It was a costly and temporarily crippling storm, but left the Texas Medical Center member institutions united in their resolve to be better prepared in the future. The lessons learned from Allison—during which FEMA reported a total rainfall of roughly 32 trillion gallons—are evident in the storm monitoring and flood mitigation measures in place across the medical center today.

Among other improvements and measures, the Texas Medical Center adopted a Hazard Mitigation Plan in 2003, designed to improve the campus infrastructure to protect at the 500-year flood level, the widely accepted rating for critical facilities like those within the medical center.

Also included in post-Allison efforts were improvements to the existing Flood Alert System (FAS), initially developed by Rice University at the request of TMC leadership in 1997. The system is one of the few radar-based flood warning systems in the United States today, and runs real-time models of rainfall for the Texas Medical Center.

“I have staff and students that watch it literally 24/7,” said Philip Bedient, Ph.D., Herman Brown Professor of Engineering in Civil and Environmental Engineering at Rice University, and the brains behind the FAS. “Allison occurred between midnight and 3 a.m. But the alert system was all automatic, and it actually worked well for as long as the power was on. The power lasted until 2 a.m., but because of the system, we knew by 1 a.m. that the medical center was going to get absolutely hammered. But there was nothing they could do at that point.”

The system includes two mounted cameras, directed at Brays Bayou.

“Those are the only cameras in all of Houston that look down at a Bayou,” said Bedient. “But the medical center really needs to know if they are about to get flooded, because they need to manage operations, surgeries, personnel… all of it. So they have a huge responsi- bility in the event of a major flood.”

The stakes are much higher for hospitals during a natural disaster than they might be for non-essential infrastructure. The institutions within the Texas Medical Center are keenly aware of their dual responsibility to the community—to protect their facilities and current patients, while also preparing to meet the need for emergency medical services that will undoubtedly arise during severe weather.

To help avoid disruption to power during a storm, all of the hospitals within the medical center house backup generators, and a plan for supplying enough fuel to keep their power on for a predetermined period of time. Many also lifted their electrical switchgear to several feet above the ground.

The campus also saw the addition of more than 170 flood doors, designed to protect the most vulnerable low-lying entryways and below-ground tunnels that connect several institutions in the heart of the medical center.

“Given what happened in Allison, here we are many years later, now the Texas Medical Center would be able to lock down and actually protect themselves pretty handedly against the return of another Allison,” said Bedient.

The Flood Management Group (FMG) was established in 2003 to help outline the policies and procedures for flood mitigation, and to manage the operation of the flood doors across the medical center. The FMG is a collaborative effort by the Texas Medical Center, Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston Methodist Hospital, CHI St. Luke’s Health-Baylor St. Luke’s Medical Center, and the Children’s Nutrition Research Center.

“The flood tunnel protection and communication plan established by the Flood Management Group includes mutually agreed upon protocol for identifying areas to protect, warning procedures for potential flooding, establishing a priority of protection and defining a flow for communication. It also defines training requirements for each participating institution,” explained Texas Medical Center Director of Security Services Cheyne Day.

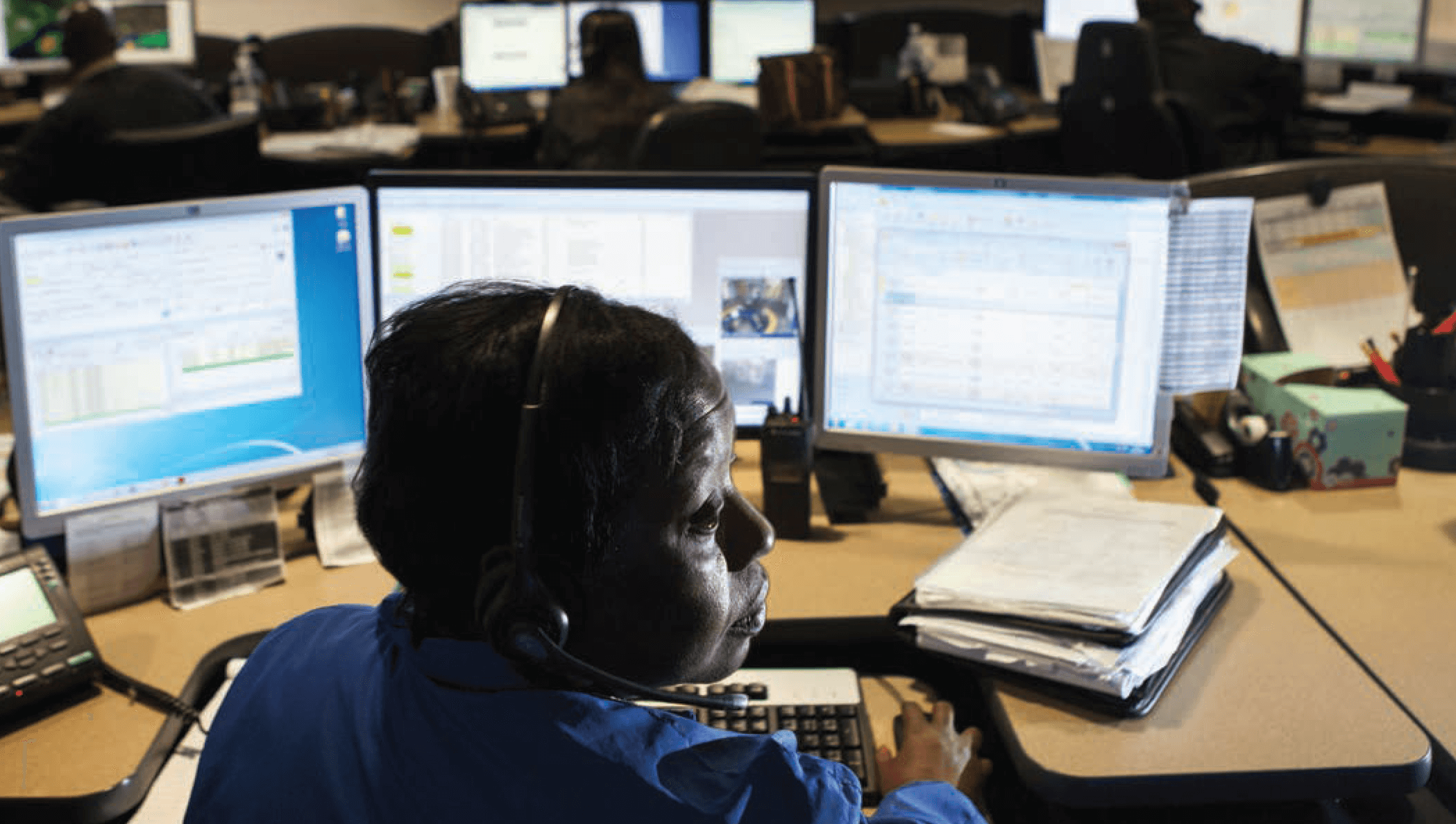

The Texas Medical Center also has a fully staffed operations center, which monitors the weather, and water levels in the bayou, around the clock. Well before the water levels reach a critical point, member institutions are in communication about the best course of action for securing the campus. Practice runs of these scenarios are conducted four times a year, to ensure all members of the mitigation teams are up-to-date on the policies and procedures for various scenarios.

“The operations center is sort of the nucleus that kind of brings together all of our member institutions,” explained

David Pollard, operations center supervisor. “It allows for the 24/7 monitoring and communications of any inclement weather or incidents. Of course, each member institution has their own communications centers, but some of their procedures and processes are predicated off of the communications that we are sending out.

“We have a very strong relationship with the Harris County Emergency Management, the Harris County Flood District, Rice University and the FAS3, so it is a joint effort,” he said. “But we do try to do our best to be the nucleus of it all, the centralized watchful eye at all times. So while everyone is sleeping, we are still monitoring and communicating.”

The medical center’s proximity to Brays Bayou, paired with the area’s often extreme precipitation makes it more susceptible to flooding. The City of Houston has sponsored improvements to the bayou and the Harris Gully, including a sizeable project to build a channel under Kirby drive, to help manage runoff through the gully.

Pollard has worked within the medical center long enough to recall the damage caused by Allison in 2001. He noted that the improvements to the Harris Gully box culvert—the tunnel that diverts water under the street— have delivered noticeable results.

“There have been so many advancements, and so much work and money put into the Harris County Gully to help keep the Texas Medical Center from flooding,” said Pollard. “It has been well tested over the past year or two and has truly held up phenomenally.”

While technology can help institutions execute an evacuation promptly or divert floodwater, there is nothing that can be done to prevent the kind of torrential downpour that the city might experience during a tropical storm or hurricane. Each institution within the Texas Medical Center is committed to mitigating—through year-long planning and investments in infrastructure—the impact that a severe storm might have on their patients and facilities. It is an ongoing effort, but one that those familiar with the medical center feel confident in.

Bedient, for one, has seen plenty of bad weather. As an outspoken advocate for better hurricane protection measures for the Houston Ship Channel, he knows well the impact that one severe storm can have on the city. But he expressed confidence in the level of protection afforded by the upgrades and monitoring within the medical center.

“In terms of getting ready for the next hurricane season, I would say that the medical center, now, within the city of Houston, is probably one of the most flood-prepared and flood protected areas in the city.”