Man on a Mission

As a child of the Depression who chased the crops with his family, Kenneth Mattox imagined he would grow up to become a missionary.

“I was from a branch of the Baptist church that said going to movies and dancing and playing cards was a sin, so a lot was expected of us,” Mattox said. “I thought, ‘I’ll be a missionary and I’ll do something to help people.’”

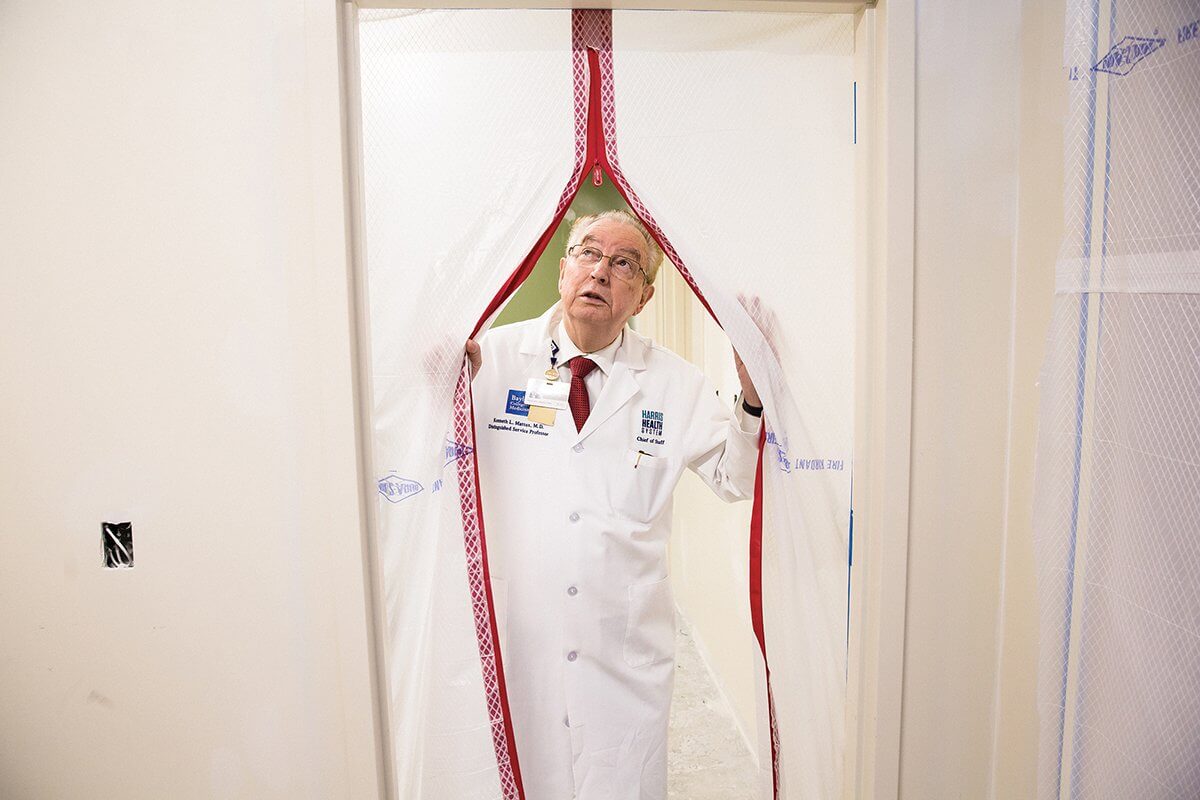

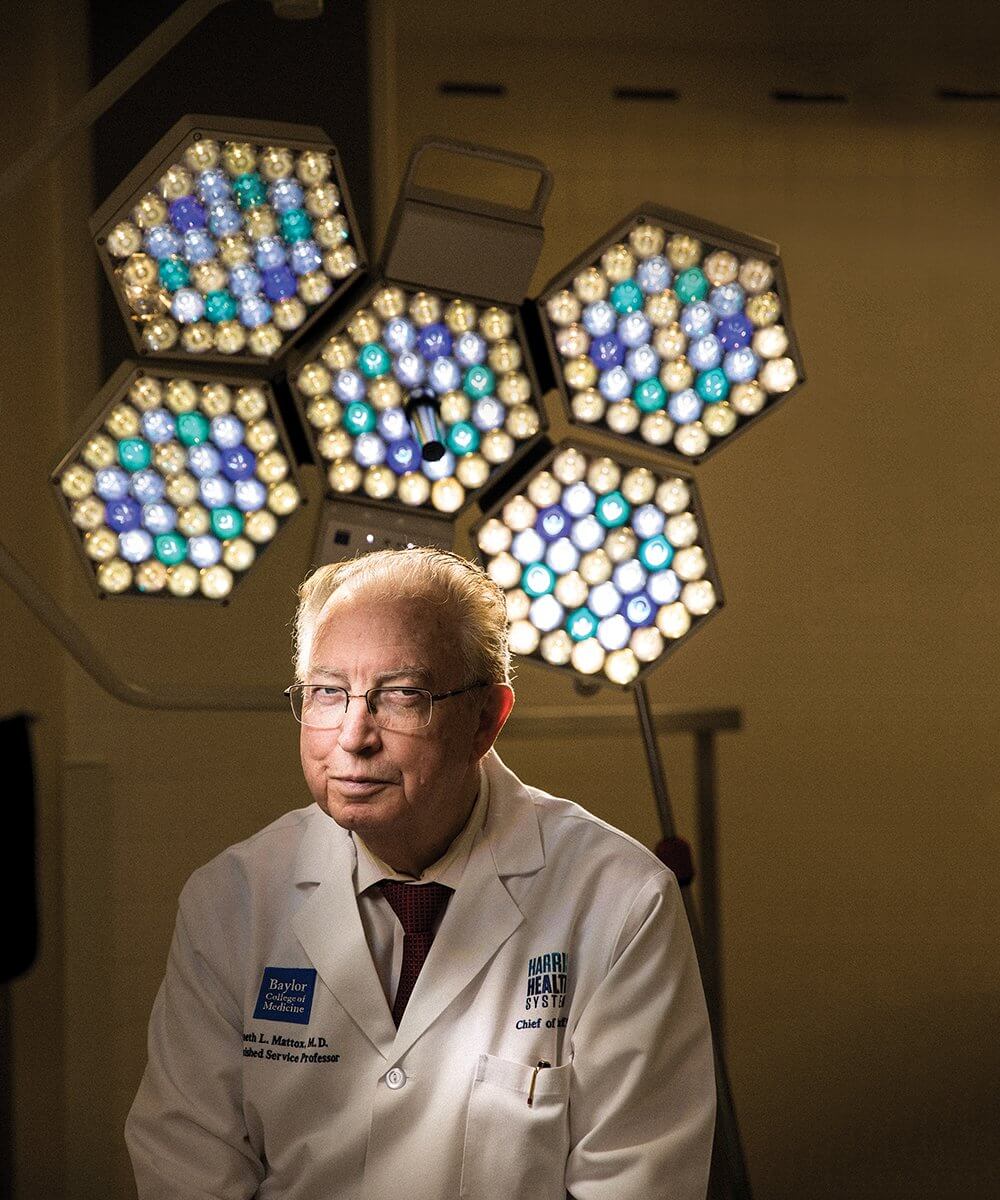

On a recent morning at Ben Taub Hospital, Mattox strode briskly through the halls of the trauma ICU, leading a group of patrons on a tour. Now 80, he is chief of staff and surgeon-in-chief of the safety-net hospital—Houston’s largest—where he has worked for nearly half a century.

Mattox found his mission in the middle of the Texas Medical Center.

“Why do I stay here? Because medicine is pure,” said Mattox, a cardiothoracic surgeon by training. “At Ben Taub, we are not going to make more money by ordering something—a drug, a test, an operation that really wasn’t needed. So it’s to our advantage to have a precise diagnosis and then do a precise operation and not add frills and bells and whistles that are not needed.”

Ben Taub Hospital is owned and operated by Harris Health System and staffed by faculty, residents and students from Baylor College of Medicine, where Mattox is a distinguished service professor.

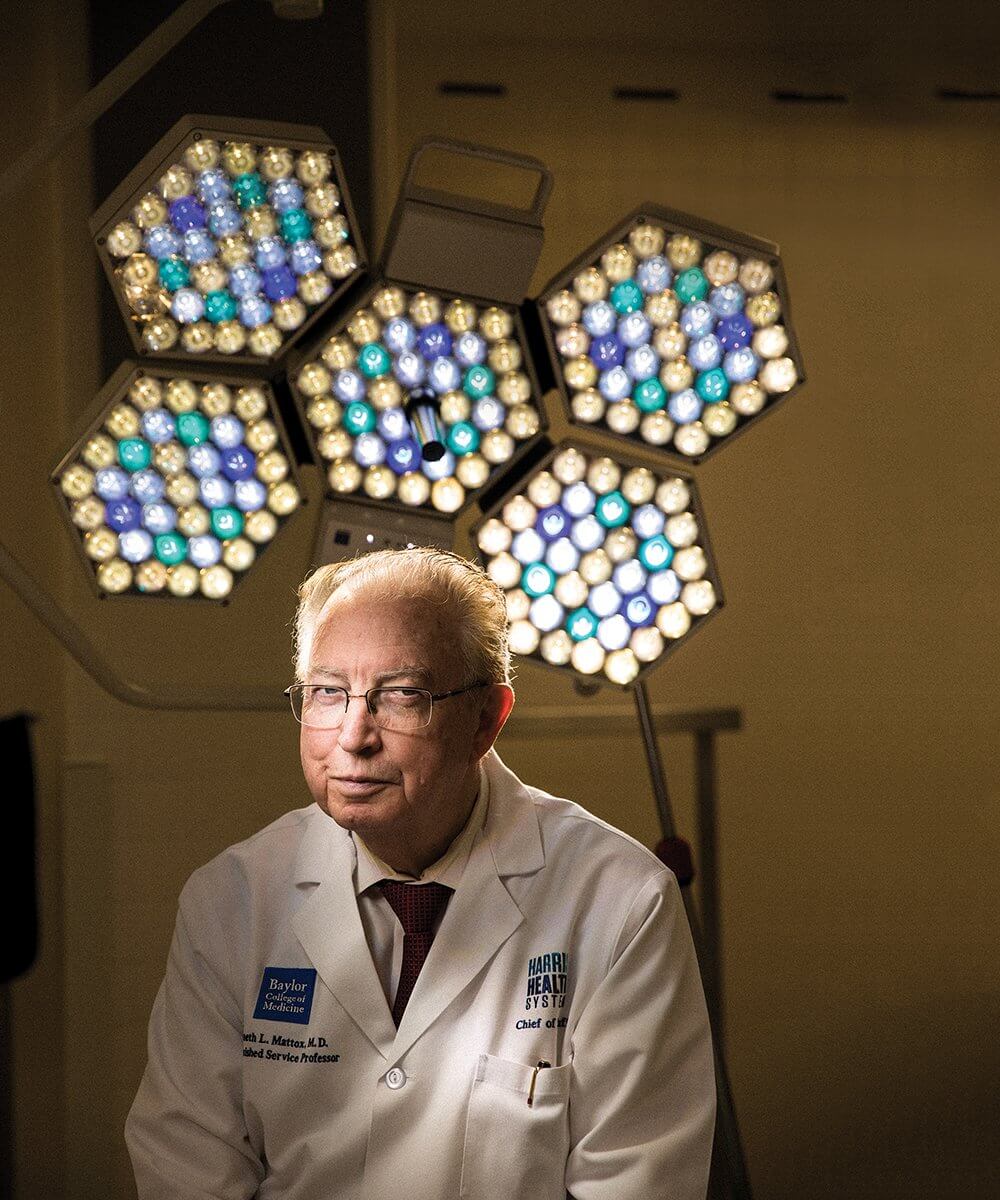

Over the course of his career, Mattox has revolutionized trauma surgery and care, worked with United States presidents and Middle Eastern royalty, and trained thousands of health care workers in the region.

As Mattox guided the patrons past the trauma ICU to the emergency room check-in, a line of patients suddenly became visible—a seemingly endless throng of people in need.

The Ginni and Richard Mithoff Trauma Center, a level I trauma center within Ben Taub Hospital, cares for 100,000 emergency patients annually.

“Ken Mattox really is the heart and soul of the Mithoff Trauma Center and Ben Taub Hospital,” said Richard Mithoff, a Houston attorney, philanthropist and Mattox’s close friend. “It is his reputation that has grown the reputation of the hospital. I can’t tell you how many trauma surgeons have told me that the very best training they ever received was at Ben Taub.”

The two men met more than 20 years ago after Mithoff was retained by a family in a high-profile case involving a police officer shooting. Mithoff raised the question of whether or not paramedics had gotten the officer to Ben Taub’s trauma center in a timely manner.

“It was memorable because when I met him, the first thing he said to me was, ‘Mr. Mithoff, I’m so glad to finally meet you. You’re going to lose this lawsuit,’” Mithoff recalled. “And he proceeded to tell me the problems with the case, which became an education for me and allowed me to educate the family and, frankly, allowed me to bring some closure to the family.”

In 2006, Ben Taub’s trauma center was renamed in honor of Mithoff and his wife, Ginni, who had donated millions to what was then called the Harris County Hospital District. The public hospital sees the city’s toughest trauma cases, from injuries sustained in car accidents to gunshot wounds. The beds and waiting rooms are always full.

“I serve here,” Mattox said, “because these people have no other option.”

Picking, singing, falling in love

Kenneth Mattox was born at the height of the Great Depression in White Oak, Arkansas— population 15—in the Ozark Mountains. His father chopped cotton for 50 cents a day. When Mattox was six months old, his family piled into a two-seater car with another family and headed west to find work. They ended up in the central valley of San Joaquin, California. For six years, Mattox and his family picked fruit and chopped and picked cotton.

In the fourth grade, Mattox moved with his family to El Paso, Texas, and then to Clovis, New Mexico, when Mattox was in junior high.

In high school, Mattox was in a band and jammed with other musicians at a recording studio affiliated with a local radio station. Occasionally, a kid from Lubbock, Texas, would come by to play. His name was Buddy Holly. One day, Holly brought along a friend from Tupelo, Mississippi. His name was Elvis Presley.

Because he was uprooted so much as a child, Mattox found solace in the church and considered becoming a minister or the next religious singing sensation. In 1956, he graduated from Clovis High School and accepted two scholarships to Wayland Baptist University in Plainview, Texas— a ministerial scholarship and a music scholarship to sing in the school’s a cappella choir.

“I’ve always known him to have a strong command in the operating room and a reputation among interns and residents as being someone you needed to pay attention to,” Mithoff said. “What I learned for the first time the other night is that he sang in the choir at Wayland Baptist and that his choir director absolutely demanded attention and attention to detail. … He credits a lot of his diligence and training in surgery to that teacher.”

Mattox also met his future wife, June, at Wayland Baptist. During his sophomore year, the Asian flu outbreak of 1957 was causing panic on campus.

“I was the school nurse at Wayland, and they had never had a school nurse before,” June recalls. “It was the days of the Asiatic flu so there were a lot of sick kids on campus.”

June had been asked by the school doctor to pass out medication to students in their dorms and that is how she met her future husband. They were married in the fall of 1959.

In 1960, the newlyweds made their way to Houston after Mattox was accepted to Baylor College of Medicine. To help her husband through medical school, June took a job as the head nurse on the pediatric oncology unit of what is now The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center.

“It was a busy time, the first few years,” June recalled. “We lived close by in a garage apartment and I was usually working on weekends and he would be studying all the time.”

DeBakey days

While Mattox was making rounds as a Baylor student at Jefferson Davis Hospital on Allen Parkway, history was in the making at the Texas Medical Center. Cardiac and vascular surgery were still somewhat primitive, but Mattox has a saying about things like that: “Go to the heart of danger and there you find safety.”

At that time, Michael E. DeBakey, M.D., was doing cardiothoracic surgery like nobody else and creating a training program that was the most disciplined in the country. That’s just what Mattox was looking for.

“The biggest challenge was what was emerging—cardiac transplantation, development of cardiac pulmonary bypass, sewing of vessels together. It required knowledge, judgment, technique,” Mattox recalled. “I wanted the toughest, hardest, highest road, the most complex training program I could find. That’s the way I’m wired.”

In 1965, Mattox was drafted into the Army to serve in the Vietnam War. When he returned in 1967, the race was on for the artificial heart. That year, a South African surgeon successfully completed the first human heart transplant.

“DeBakey was working on the artificial heart in his laboratories at Baylor when Christiaan Barnard transplanted the heart and the world went crazy and everybody started playing the ‘me too’ game,” Mattox said. “The laboratories, limited in size, were switched from doing artificial hearts to doing transplants. Dr. Domingo Liotta, who was doing the work with the artificial heart, was kicked out of his lab—not fired, but he didn’t have a place to work.”

As Mattox recalled, Denton Cooley, M.D., acclaimed heart surgeon and former protégé of DeBakey, bumped into Liotta one day and asked, “Why do you have such a long face?” Liotta, who had been working closely with DeBakey, answered, “Because they kicked me out of my lab.” Cooley responded: “Well, you know I am a member of the department of surgery.

I have extra space over at St. Luke’s Hospital. Why don’t you come work with me and bring your equipment?”

On April 4, 1969, Mattox was still a resident training in general surgery when he was called in by Cooley to observe one of history’s most groundbreaking surgeries.

Cooley had found a patient who needed an artificial heart: Haskell Karp, a 47-year-old man dying of heart failure. DeBakey and Liotta had been developing an artificial heart through funding from the National Heart Institute. They had tested the heart in four calves, but all of them died within hours of their surgeries.

Nonetheless, Cooley was determined. DeBakey was out of town, and Liotta went to the lab and procured the artificial heart for Cooley’s patient. Cooley and Liotta became the first surgeons to implant a total artificial heart in a human body.

“I’m probably the only one left who was in the room that day,” Mattox said.

Mattox said he was one of the first people to see DeBakey after he got back to Houston and discovered, from a newspaper article, that Cooley had put his artificial heart in a patient. And thus began the famous feud between Cooley and DeBakey that lasted for half a century.

Surgeons—especially surgeons in Houston— are the world’s largest concentration of mass, raw ego, Mattox said. They are fiercely competitive and they often try to outflank each another, just like athletes.

“It was wonderful training with Dr. DeBakey,” Mattox said. “He was a tremendous taskmaster, but he expected nothing of anyone else that he didn’t expect of himself. He considered sleep a bad habit. He would run up nine flights of stairs. He was totally dedicated to his patients and he was always looking for a better way. In essence, that is what medicine is all about.”

Shock and awe

In 1973, Mattox began his career at Ben Taub as deputy surgeon-in-chief, director of emergency surgical services and chief of thoracic surgery service. With so many new responsibilities, he began recruiting a strong support staff—beginning with his assistant, Mary Allen.

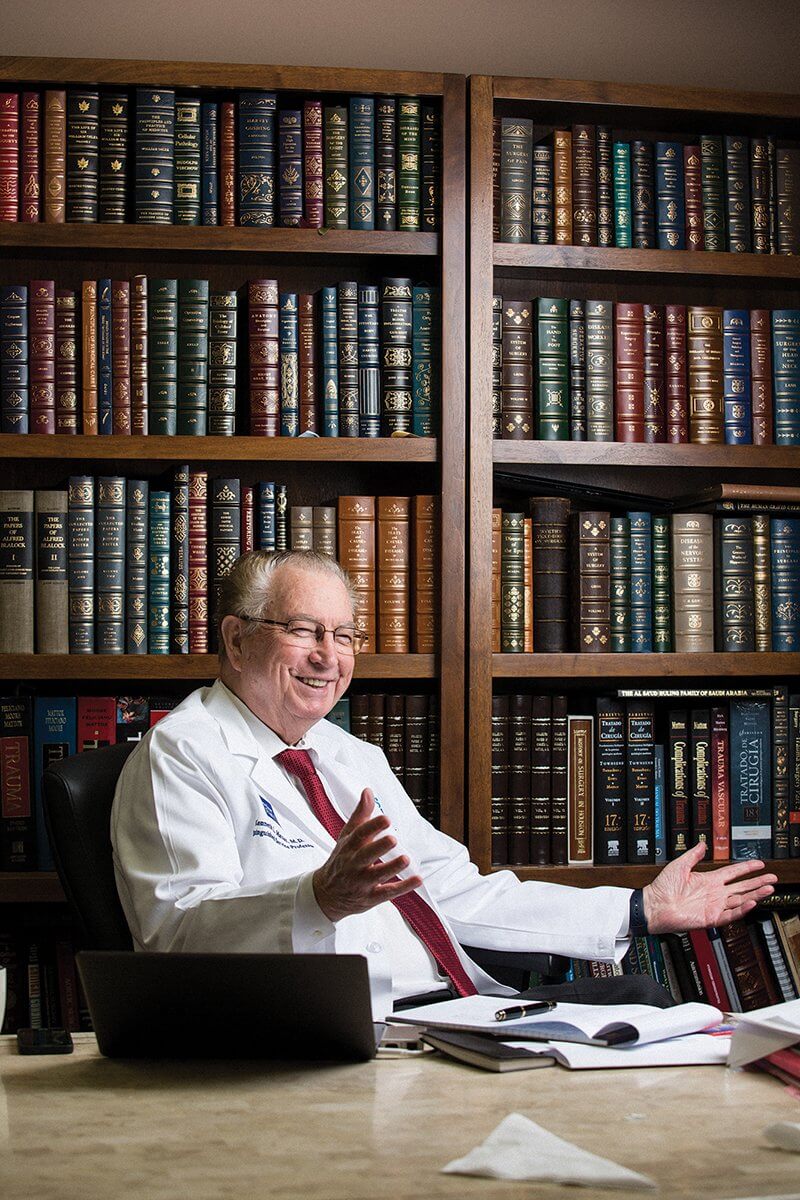

“Mary has been with me since the first day I started—almost 50 years,” Mattox recalled. “She knows things I have long since forgotten.”

Today, the two work in side-by-side offices lined with books written by Mattox and edited by Allen, photographs of Mattox with world leaders, and a jumble of awards, honors and plaques. Throughout the work day, Mattox frequently calls Allen into his office to discuss ongoing and upcoming projects.

“He always impresses me with his enthusiasm for his job and what he does for the patients. His dedication never wanes,” Allen said. “A lot of people get burned out and frustrated, but he never does. Anything that other people would consider frustrating or challenging, he considers an opportunity.”

Mattox took over as chief of staff and surgeon-in-chief at Ben Taub Hospital in 1990. His training and resourcefulness in the military, as well as years of experience in cardiac and general surgery, elevated the hospital’s reputation for trauma care. Among his notable practices: Maintaining low blood pressure in trauma victims to keep their bodies in a state of shock.

“Shock is actually beneficial, and that idea was started by me. During the Gulf Wars, we had hypotensive resuscitation,” Mattox said, referring to the practice of maintaining blood pressure in the lower than normal range when a patient experiences continuous bleeding during an injury. “We did not take blood pressure cuffs to war, we only talked to the person and asked for their name, rank and serial number and felt for a pulse. If they had either of those, we didn’t operate on them immediately. If they were losing those, we’d cut them and took care of what was bleeding.”

Mattox’s name has become synonymous with trauma care. His textbook, Trauma, co-written with Ernest E. Moore, M.D., and David V. Feliciano, M.D., is the definitive guide to trauma surgery. Mattox has made significant breakthroughs in trauma resuscitation—specifically regarding shock, trauma systems, thoracic trauma, vascular trauma, auto transfusion, complex abdominal trauma and multi-system trauma. One trauma technique even bears his name: The “Mattox Maneuver” refers to the mobilization of the descending colon to the midline to expose the abdominal aorta.

Mattox is so well known in trauma circles that Vanity Fair magazine asked him to weigh in on what really killed Princess Diana. His conclusion: heart herniation.

“In cases of extreme lateral shocks,” Mattox told the magazine in October 2004, “the heart can burst through the pericardium and lodge in the left or right side of the chest. We know [from the medical report] that Diana was sitting sideways, facing the other rear passenger, so her heart would have herniated to the right. That would have stretched the left pulmonary vein so far that it tore at the point of attachment.”

Mattox said it was probably pericardial strangulation, rather than internal bleeding, that caused Diana’s sudden cardiac arrest in the Paris tunnel.

“Informing the world of the total truth puts this thing to closure,” he told Vanity Fair. “We never reached it on J.F.K., but maybe now we can on Diana.”

Katrina, Clinton and Obama

Part of Mattox’s mission at Ben Taub is to keep costs affordable for patients.

For example, a CT scan sets providers back about $75 in incremental cost, Mattox said. However, some private hospitals may charge what it costs to buy the machine—$2,225. At Ben Taub, Mattox said, the patient is billed $75 for a CT scan because that’s what it actually costs.

“Part of it is me,” Mattox said. “I’m the only person on either side of my family, with maybe one exception, who ever went to college. A bunch of dirt farmers. For six years of my life we were migrant farm workers. I had no house, no tent, slept on the ground in California. … I realized if I have someone who comes in the emergency room, they may not need all of those tests and scans.”

Mattox estimates 60 percent of what is done in medicine today is unfounded in scientific fact and done simply because it is what has always been done.

“All of the dogma of you’ve got to get blood pressure, start an IV…” Mattox began. “In the Texas Medical Center, 95 percent of the CT scans that we obtain do not alter decision making. They make the hospital rich, but you really don’t need them. [They’re] unnecessary and we are exposing people to radiation.”

When Hurricane Katrina hit the Gulf Coast in 2005, Mattox was among the medical professionals and city leaders who ran operations at the Astrodome, where 25,000 evacuees from the New Orleans area had landed. Mattox leaped into action to build a clinic in the stadium and provide care to a traumatized population—the same way he does at Ben Taub.

“During Katrina, Hillary and Bill Clinton were in Houston. I was in the same room with Nancy Pelosi, Hillary and Bill Clinton, George and Laura Bush, and Barack Obama,” Mattox said. “I found myself beside Obama—he was not running for president yet. … I said, ‘Thank you for coming to Houston. I’m glad you see the way we do things here. If you are looking for a cost-effective way to provide public health care, look no further than the contract and the partnership between Baylor College of Medicine, Harris County Health Department and the Houston business community. We have done it right.’”

But Mattox doesn’t feel like any of the politicians heard him, and he points to the failure of the Affordable Care Act as proof. He believes the legislation does not help patients or hospitals. Washington should have listened, he said.

Mattox still shares his thoughts with politicians, even on Twitter. He said he has been asked by presidents on both sides of the aisle to serve on their respective staffs, but never accepted.

“Nothing about a political party drives me,” Mattox said. “It’s about doing the right thing with the resources that we have. If I have a political philosophy, it is that our family expressions, our educational experiences, our disaster response, our churches that we go to, our health care delivery is always local. Always local.”

An orchestra, a team

Mattox and his wife evacuated their home in Meyerland last August when floodwaters from Hurricane Harvey forced them out. They raised their daughter in that house, and had to say goodbye to half a century’s worth of memories.

Late last year, the couple moved into a new home in Houston’s Afton Oaks neighborhood. Mattox called in the family troops—his daughter and three grandchildren—to help unpack.

“I made them all come down here during Christmas,” Mattox said. “We had just found our replacement house after the flood from Harvey. We were living in a house that had a bed that we could sleep on and a table we could eat on. Everything else was a jungle of boxes. So I said, ‘You all come down here for Christmas,’ and I put them to work unpacking.”

Mattox also took his entire family to New York City, where they saw the musical “Hamilton” on Broadway. These days, he has more time for family trips.

Although he no longer practices medicine, Mattox remains deeply involved with day-to-day life at Ben Taub and looks after Baylor’s interest in the hospital.

“Ken Mattox is a terrific ambassador for Baylor College of Medicine,” said Paul Klotman, M.D., Baylor’s president, CEO and executive dean. “Not only is he a highly skilled trauma surgeon, but he has been a steadfast leader for both Baylor and Ben Taub Hospital. His focus continues to be on assuring that patients receive the highest quality of care and that the next generation of physicians are provided outstanding educational experiences. We are fortunate to have him.”

Ben Taub Hospital is currently in the middle of a $250 million renovation that encompasses multiple projects.

“We are almost going to be doubling our capacity in the operating rooms, which will be a great thing for our patients and medical staff,” said Mike Staley, vice president of operations at Ben Taub and Harris Health System. “When the hospital was built, the code requirement was 400 square feet. Now the smallest a room can be is 600 square feet.”

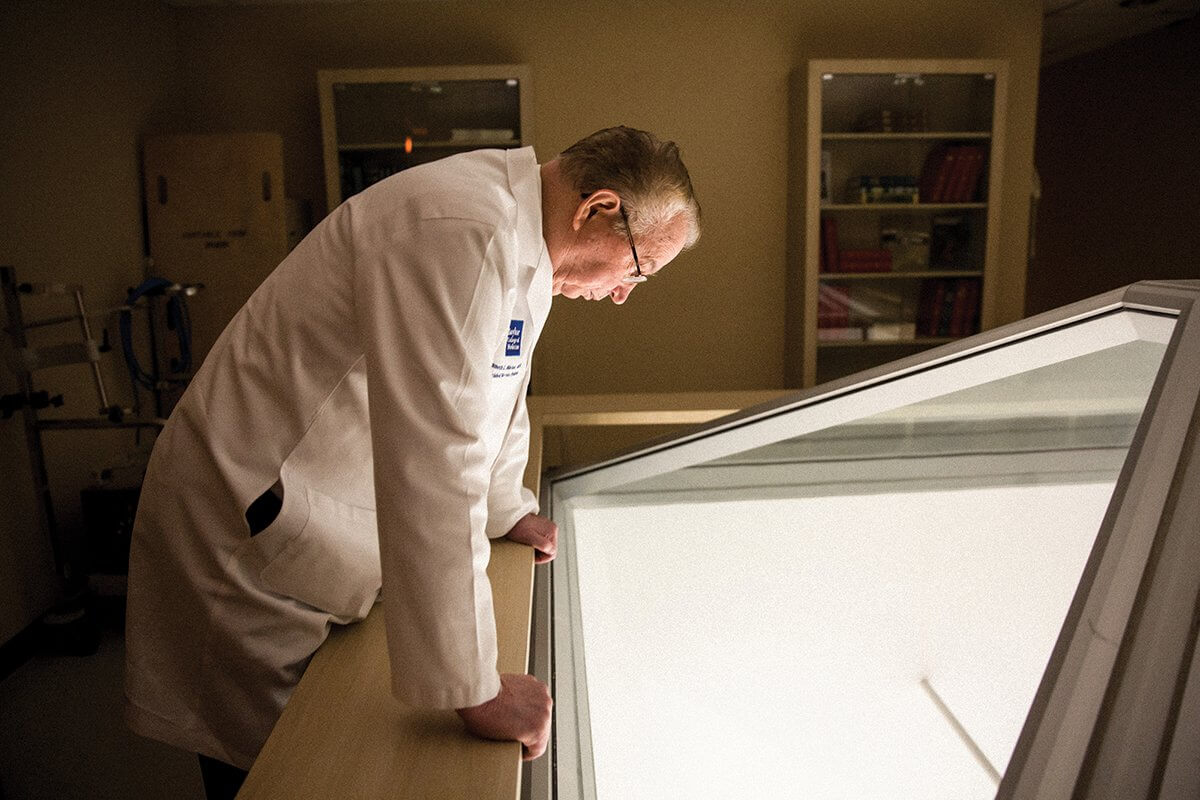

During regular rounds this spring, Mattox led a group to an observation dome overlooking the trauma operating room—the same room where RoboCop 2 was filmed in 1989.

On this particular day, one of Mattox’s many trainees, Matt Wall, M.D., was performing a coronary bypass.

“What you see here is an orchestra, a team. Everyone has their particular job to do and everyone knows what part of the operation is next,” Mattox said, gazing down on the surgery in progress. “Any teacher … you have to reach the point that you realize you have sired another brain that is another person and your job is to teach the fundamentals, the skills to make judgment, and to move forward and to trust them with your life.”

Mattox trusted Wall with his life.

“In 2001, after being up for about 48 hours, I went to a conference at 7 a.m. and I didn’t feel so good,” Mattox said. “I thought, ‘This may be heart,’ so … I decided to go up six flights of stairs to cardiology at Ben Taub.”

Within 20 minutes, Mattox had a coronary arteriogram that showed a blocked artery. Wall was part of a team of doctors that opened him up and performed emergency heart surgery.

That teacher-student cycle is as reliable as the steady stream of patients who come to Ben Taub Hospital for care.

“The patient population has gotten bigger since I started, but patients a thousand years ago and patients now are the same,” Mattox said. “They hurt, they broke something, they drank something they didn’t need to drink, they developed an infectious disease …”

Patients don’t really change, Mattox said, and neither do the people who care for them.

“People become doctors because they want to relieve suffering,” he said. “And, quite honestly, this kind of practice, this kind of hospital and this kind of community has a mission feel.”