Ready to Reset

Sitting in bed in a recovery room at Ben Taub Hospital, Natalia Rodriguez waits for her 35th maintenance treatment of electroconvulsive therapy.

“I’ve always had my depression, but I didn’t recognize it until way later, because I didn’t want to,” Rodriguez said. “I didn’t want to appear weak in front of my kids. I had to be strong so I just worked, worked, worked. And then it hit me.”

In 2011, Rodriguez was diagnosed with severe depression. She began taking antidepressants.

“At first, I was at another facility and they gave me all kinds of medicine, and it was so bad, it gave me hallucinations for a month,” Rodriguez said. “After that, I ended up at another facility—an inpatient clinic—because I was having such bad crying spells.”

After she was discharged from the hospital, her depression continued and the medication did not help.

“I think the depression was brought on by everything that I have been through,” she said. “I was molested when I was young. … I have been in and out of prison, had low self-esteem.”

Although she worked full-time in the billing department of an orthopedic clinic, Rodriguez struggled to support her three children. She was sent to prison in 2005 on a drug-related conviction and served for almost five years.

In prison, Rodriguez said she was a leader in a block with 180 women. “I ran the county, I ran it,” she said. “They saw me as a person in charge.”

After she was released from prison, depression consumed her. Weeks went by when she didn’t leave her room. When she tried to commit suicide, her care team finally realized she required immediate attention. In 2013, Rodriguez began receiving electroconvulsive therapy (ECT).

“They ended up sending me to another facility and that’s where I was introduced to ECT, but there they treated you like it was a revolving door,” she said. “So I didn’t know what was happening; they just told me that I needed to do it.”

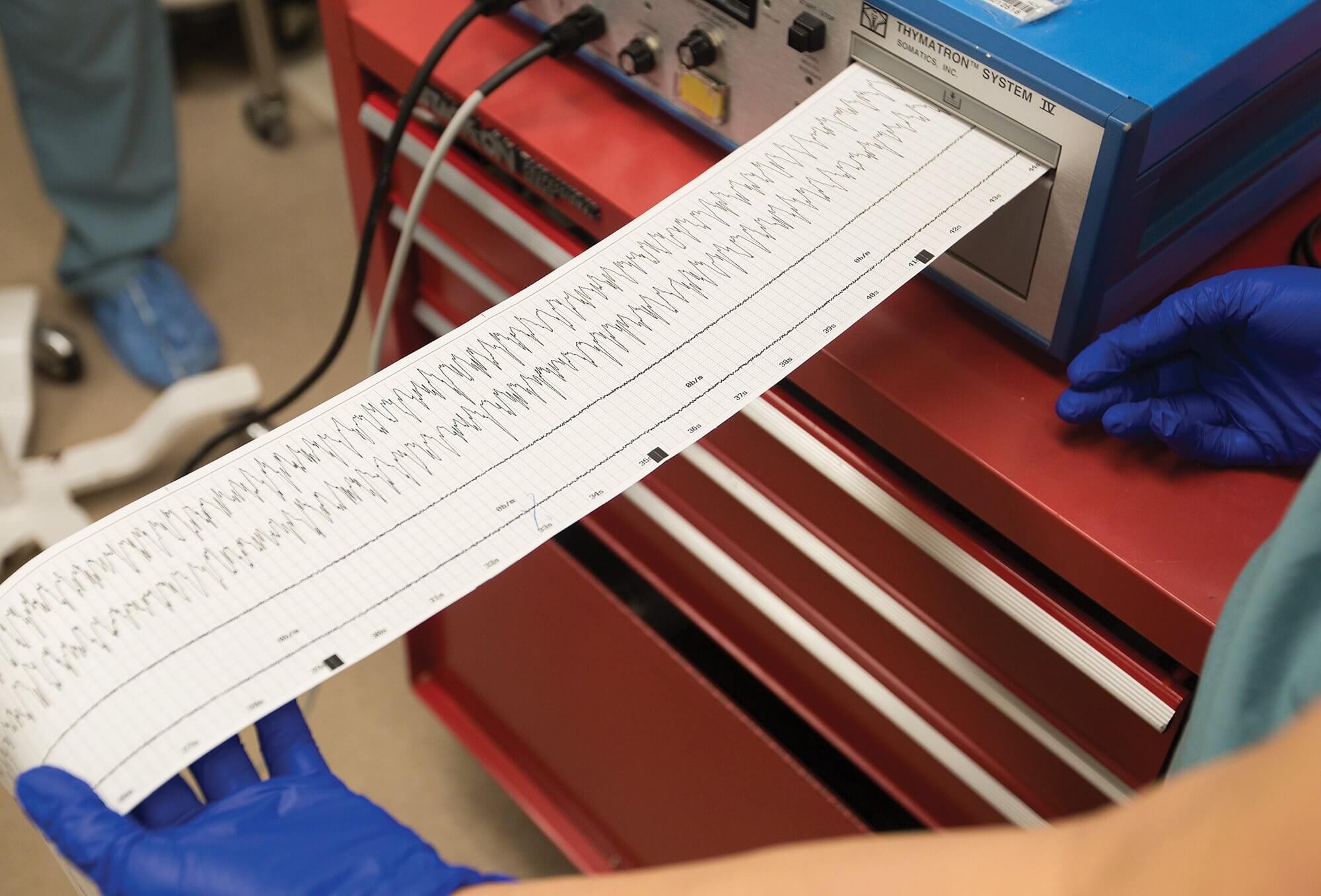

ECT, sometimes called shock therapy, is used mainly when antidepressant medication fails to treat severe depression. The procedure pushes small electric currents through the brain to trigger a brief seizure, which changes the brain’s chemistry and, in many cases, reverses the symptoms of some types of mental illness.

Bilateral treatments

In 2014, Rodriguez found her way to Strawberry Health Center in Pasadena, Texas—an outpatient clinic that is part of Harris Health System. She began working with Robin Livingston, M.D., medical director of ECT services at Ben Taub Hospital.

“When I met Natalia, she was severely depressed and had attempted suicide,” Livingston said. “Because of that, we decided to give her bilateral treatment, which is electrodes on both sides of the head.”

When a patient receives unilateral treatment, the seizure occurs only on the left side of the brain, causing fewer cognitive side effects. When a patient receives bilateral treatment, the seizure occurs on both sides of the brain. Bilateral treatment is not proven to work better, but it is proven to work faster.

Asim A. Shah, M.D., chief of psychiatry at Harris Health System and Ben Taub Hospital, brought Livingston to Ben Taub to restart Harris Health System’s ECT program. “ECT is truly the best treatment when it comes to treating depression,” Shah said. “There is no treatment that works as quickly as ECT. Antidepressants have an efficacy of 40 to 45 percent. ECT has an efficacy of 70 percent. Why should we not use a treatment that works for 70 percent of people?”

Once a seizure has been stimulated, it will last anywhere from 25 seconds to two minutes. The seizure changes the neurochemicals in the patient’s brain, which works in various ways. ECT has been proven to increase serotonin, increase norepinephrine, decrease dopamine, work as a brain cell stabilizer and reduce stress.

“It’s not one single thing ECT does that is helping psychiatric patients,” Livingston said. “It is a combination of all of these things, and that is why it is our gold standard for neurostimulation treatments.”

The ECT program at Ben Taub performs dozens of treatments every week—on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays. Prior to a treatment, patients are given a muscle relaxant and general anesthesia. Once the patient arrives in the operating room, the care team ensures the patient is comfortable and sedated before initiating the shock. The shock results in two seizures—one in the brain and one in the body. The seizure produced in the body is only visible

in the patient’s left foot, where it is monitored by the doctor. The procedure itself does not take that long, but due to the use of general anesthesia, patients require time before and after to recover.

“I’m normal now”

While ECT is an effective treatment for patients suffering from treatment-resistant depression, it does not work for everyone and it cannot be administered to patients without their informed consent.

In Texas, a patient must give their own consent for each ECT treatment they receive. Family members, guardians and doctors cannot give consent for the patient.

“Texas has some of the strictest laws regarding ECT in the nation,” Livingston said. “ECT has had proven success in patients suffering from severe depression, and I believe it could help many patients with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. This can be a barrier if a person is not capable of giving their consent.”

Livingston is well aware of the negative stigma attached to ECT, mostly because of its depiction in films like One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.

“For a long time, ECT was seen as a very cruel treatment,” Livingston said. “When it came out in the 1930s and ’40s, there was no anesthesia, so people’s bones would break from the jolt. But that is not the case now. It is very safe and effective.”

Today, because of the success of her ECT treatments, Rodriguez said she is enjoying life for the first time.

“I’m normal now,” she said. “I walk my dogs every morning. I get up and make breakfast, see my grandkids—I’m just active all day. I make friendship bracelets for my nieces, teach my grandson how to do art. Last fall, I took my first flight to Chicago for a family reunion and I was a little scared, but I made it and it was okay.”

Rodriguez receives maintenance ECT treatments once every six weeks. She also sees her therapist once a month, in addition to taking antidepressants.

“I recommend ECT to people that are in really bad shape, because it really helps,” Rodriguez said. “I tell them it’ a choice they have to make themselves, and they really need to see a therapist and a psychologist to really decide what they need to do. But I recommend it to anyone that is really trying to feel better. … It’s a life-changing experience.”