Building a City of Medicine: The History of the Texas Medical Center

At the turn of the 20th century, Monroe D. Anderson, a banker and cotton trader from Jackson, Tenn., along with his brother and brother-in-law, founded a successful cotton merchandising firm called Anderson, Clayton and Co. The profits they generated continue to benefit the community to this day, thanks to the massive endowment created by Anderson for “the betterment and welfare of mankind.”

Although he was not born in Houston, Anderson’s love for the city was fostered when he was a young man. In 1907, after leaving his hometown to capitalize on Houston’s growth as a financial center, Anderson quickly realized the city’s tremendous potential. “Mr. Anderson had a wide acquaintance among Houston people, but he was reticent and had the appearance of being shy,” said Colonel W. B. Bates, one of Anderson’s close friends and attorneys. “Only a few people knew him intimately. Those who did admired and loved him.”

In conjunction with Bates and John H. Freeman, Anderson created the MD Anderson Foundation in 1936 to keep his business partnership, Anderson, Clayton and Co., from dissolving due to estate taxes in the event of his death.

Anderson exercised caution in his management of money and property, a likely result of the aftermath of the Civil War and the financial toll of Reconstruction. It was only fitting, then, that the trustees of his estate would be deliberate in their allocation of his fortune, to be used “[for] the establishment, support, and maintenance of hospitals… the promotion of health, science, education, and the advancement and diffusion of knowledge.”

Upon Anderson’s death, the foundation, as the principal beneficiary of his estate, received over $19,000,000 in funding. It was the largest charitable foundation ever created in Texas. Although Anderson became ill and died before he could formalize any specific plans for the funds, he met regularly with Bates and Freeman to discuss his ideas. “He came by the office almost every morning to talk things over,” recalled Freeman. It was Bates and Freeman who determined how to best fulfill Anderson’s wishes.

They sought a project that would bring the greatest good to the greatest number of people. They named Horace M. Wilkins, president of the State National Bank, as a third trustee. Knowledgeable in law, finance, and Houston’s rich history, Freeman, Bates and Wilkins started to develop a plan that would realize Anderson’s dream, and one day lead to the creation of the Texas Medical Center.

Ernst W. Bertner, M.D., a native Texan who graduated from The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston in 1911, was instrumental in the development of the Texas Medical Center. For many years, Bertner traveled across the United States and throughout Europe to study and analyze the great medical centers of the world. Dreaming of a modern “City of Medicine,” a contemporary reimagining of those described in Greek mythology as the domain of Asclepius, Bertner keenly saw the advantages of bringing together all aspects of medical education and patient care in one physical location.

Bertner, along with Frederick C. Elliot, M.D., dean of the then unaffiliated Texas Dental College of Houston, were key figures in sparking the Anderson trustees’ interest in medical institutions. They encouraged the public’s interest in bringing a medical school to Houston, which could be used as a focal point to form a great medical complex of research and healing institutions.

On June 30th, 1941, two years after Anderson’s death, a single legislative decision gave these ambitions a solid foundation upon which to build: Texas Governor Lee O’Daniel signed House Bill 268, which authorized a state cancer research hospital and appropriated $500,000 towards its construction. State Representative Arthur Cato drafted the bill out of a personal interest in cancer research. His wife’s parents and his own father had died from cancer.

The Anderson trustees recognized the value of House Bill 268, contacting Homer Rainey, M.D., the president of the University of Texas at Austin, almost immediately. A series of informal conversations followed, including several on the back porch of Bates’ home. These conferences led to the announcement on March 27th, 1942, that the new cancer research hospital would be located in Houston. In late September, the Board of Regents formally announced that they would name the hospital The M.D. Anderson Hospital for Cancer Research of the University of Texas.

“We believe Houston, more than any other city in this part of the world, offers the best opportunity for a medical center,” said Rainey.

The trustees learned of a 134-acre piece of property owned by the City of Houston, just south of Hermann Hospital. William Hogg, son of Texas Governor Jim Hogg and a University of Texas regent as well as a developer of River Oaks in Houston, was selling the land back to the city. Despite repeated attempts, Hogg had been unable to get The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston to move to Houston and build adjacent to Rice University and Hermann Hospital.

Three miles from Houston’s downtown, the site, 134 acres of mosquito infested forest, was considered too far outside of Houston to be valuable to the University of Texas.

The trustees of M.D. Anderson’s foundation, however, realized that it was “the logical place to build a medical center.” Hermann Hospital, which opened in 1925, was on the northern bounds of the site and the then Rice Institute, now Rice University, was only a short distance away; both institutions were well positioned to benefit the medical center. The trustees moved quickly and decisively. On November 6, 1943, the MD Anderson Foundation and the City of Houston reached an agreement for the purchase of precisely 134.36 acres of land located south and east of Hermann Hospital for use as a medical center. A full page ad in The Houston Post urged Houstonians to vote the next day and support the idea to develop a medical complex. Voter approval was necessary because the site was designated as city park land. Fortunately, Rainey’s announcements the previous year had excited great civic interest in the community. The sale was approved by the people of Houston on December 14, 1943.

While plans for the cancer hospital and the Texas Dental College affiliation with the University of Texas were being developed, trustees of the then Baylor University College of Medicine, then located in Dallas, approached the Anderson trustees with a proposal that the college be moved to Houston and incorporated into plans for the medical center. In May of 1943, Baylor University College of Medicine received an offer from the MD Anderson Foundation for both land and startup funding. Baylor emerged in the center of the Texas Medical Center forest while, simultaneously, construction on MD Anderson began.

The dream was taking shape, slowly forming the familiar landscape of the Texas Medical Center. On November 1, 1945, just one month after Japan surrendered to formally end World War II, the Texas Medical Center was chartered under the laws of the State of Texas as a non-profit corporation. “Other than the agreements restricting the use of the land to non-profit use in medical care, teaching and research, there were no strings attached,” said Freeman. “Every one of the institutions was absolutely autonomous and still is.”

In the 1950s, The Methodist Hospital, St. Luke’s Episcopal Hospital, and Texas Children’s Hospital all broke ground. Their success served as acatalyst, driving others to join the Texas Medical Center’s community of non-profit health care institutions. By 1954, Texas Medical Center corporate offices were created to oversee land distribution and develop the common areas for the new medical city.

The Texas Medical Center, with its charter registered, began making gifts of land from its original property. The MD Anderson Foundation was able to contribute substantial funds for building programs to the recipients of the land. Since 1945, the Texas Medical Center has gifted or leased more than 113 acres at almost no cost to various member institutions.

“I think Mr. Anderson, if he saw this medical center today, would say, ‘I see it out there, but I don’t believe it,’” said Freeman in 1973. “It’s all there, and you can reach out and touch it. It’s real.”

Today, the Texas Medical Center has 54 member institutions, composed of 27 government agencies and 27 not-for-profit health care facilities. This past year, 7.1 million patients visited institutions within the Texas Medical Center. The mission of the Texas Medical Center, and its member institutions, has always focused on providing the best in not-for profit health care for patients, the best in academic training for health professionals at all levels, and support of medical research.

National recognition was generated, in large part, as a result of the incredible work that has come out of the Texas Medical Center through the decades.

Michael E. DeBakey, M.D., a young doctor from Louisiana, performed the first successful carotid endarterectomy in 1953, establishing the field of surgery for strokes.

William Spencer, M.D., often thought of as “The Father of Modern Rehabilitation,” was renowned for establishing one of the first polio treatment centers in the nation and the institute he founded, The Institute for Rehabilitation and Research, created a Spinal Cord Injury Program that became the model for the nation’s disability centers.

In the 1960s, Denton A. Cooley, M.D., and his colleagues designed new artificial heart valves, and the mortality rate for valve transplant patients fell from 70 to just eight percent.

Other distinguished doctors gained national and international acclaim in various fields through the organizations they served. In 1998, Ferid Murad, M.D., Ph.D., chairman of Integrative Biology and Pharmacology at The University of Texas Health Science Center’s Medical School, was awarded a Nobel Prize in Medicine. It marked the second Nobel commendation for a Texas Medical Center physician, following in the footsteps of Roger Guillemin, M.D., Ph.D., who received the 1997 Nobel Prize in Medicine for his role in “the discoveries concerning the peptide hormone production of the brain.”

Collectively, these milestones are a source of pride within the Texas Medical Center. Founded in 1976 by James “Red” Duke, M.D., Memorial Hermann Hospital’s Life Flight was one of the first emergency medical air transport programs in the nation.

David Vetter, the famous “Bubble Boy,” born in 1971 with an immune deficiency, lived in a specifically designed bubble at Texas Children’s Hospital, where he played, slept, ate and attended school. Study of his condition led to significant contributions in the research of immune system disorders.

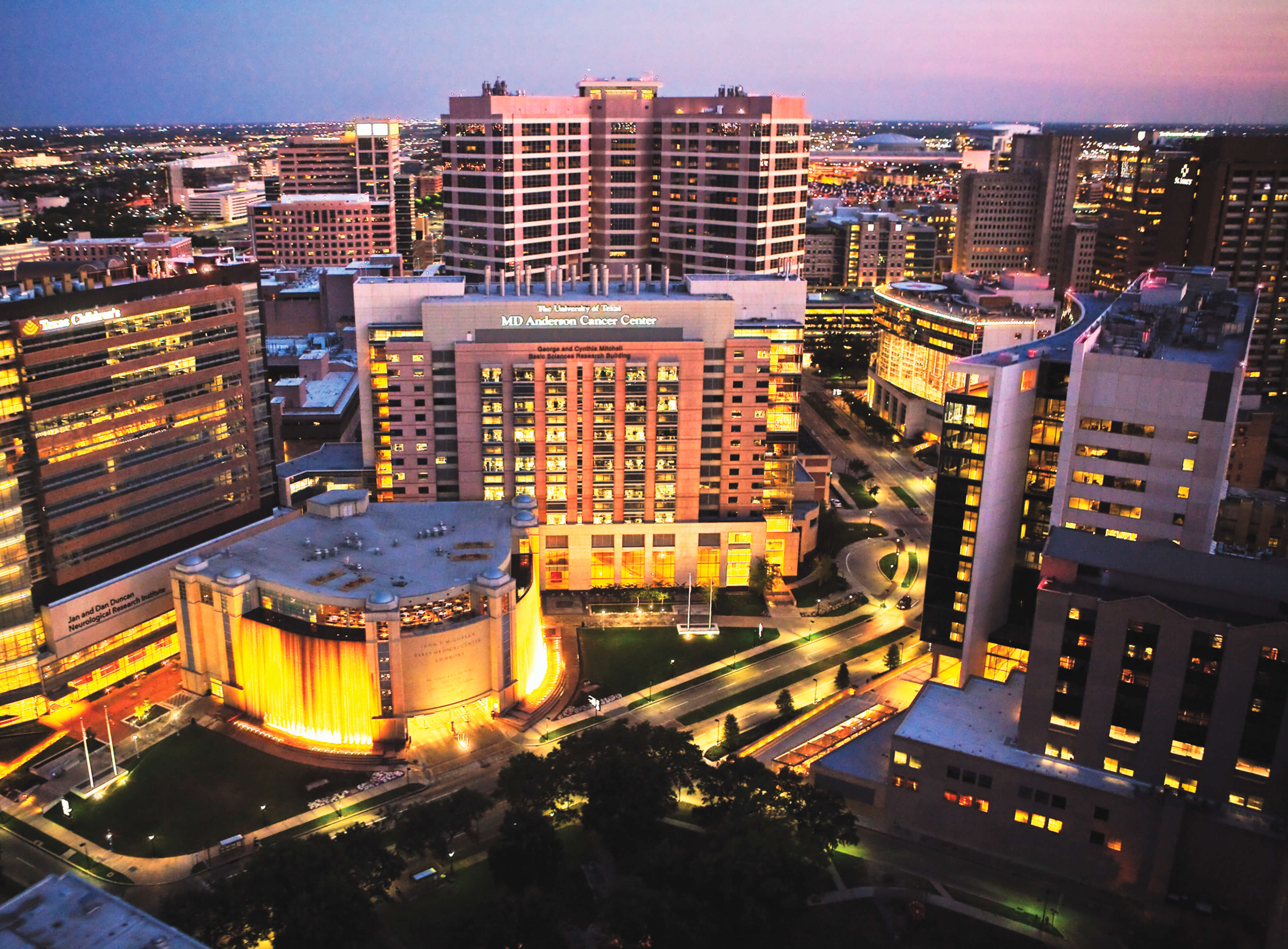

Already holding the title of the world’s largest medical center, the Texas Medical Center’s physical growth in the past few decades has skyrocketed. With a sprawling campus that receives over 160,000 visitors daily, the Texas Medical Center alone ranks as the 8th-largest downtown business district in the United States, right after Philadelphia and Seattle.

In recent months, the momentum of the Texas Medical Center’s new strategic vision, designed to advance the medical center as a world leader in life sciences, has intensified. Since January’s two-day Strategic Planning Retreat, the Texas Medical Center is making strides toward its collective future.

Leaders within the Texas Medical Center have come together in support of five initiatives, with a special emphasis on collaboration, to usher the 54 member institutions into the future. Their vision falls squarely in line with the original plan set in motion by Anderson nearly a century ago: “to the promotion of health, science, education and advancement and diffusion of knowledge and understanding among the people.”